Publishers have beaten the revenue diversification drum for years. Subscriptions and direct reader revenue are some of the healthiest ways to operate commercial publishing businesses, especially as the ad business gets more difficult.

Over the past couple years, many publishers that had been fully ad supported, or event supported began experimenting with reader revenue. Some early adopters, like Slate, regarded it as a nice source of incremental revenue, a way to extract more from their most passionate readers. Others, like BuzzFeed News, saw it as a way to establish a deeper connection with the readers that might help them continue to build and develop as a new brand.

How all those different experiments go may determine whether those subscription-curious publishers survive the next couple of years.

It’s even more important now: Digital advertising has long been a tough business to be in, but for the next several months – never mind the next couple years – it figures to be almost impossible for many publishers and media companies.

In just two months, digital ad spending has dropped by more than 30%, according to the IAB. More traditional formats, especially print, have slid even more, fast-forwarding secular declines that many legacy publishers were hoping would happen at a slower pace. And economists all expect that it could take years for the American economy to fully recover from this nascent recession.

That extra pressure, on top of the normal competition they face, will force publishers to decide how seriously they will pursue consumer revenue. While not every publisher needs to be subs-first, or even plan for subs to deliver as much revenue as ads, each needs a firm sense of how reader revenue fits, not just into their business model but into their brand identity.

In this guide, we’ll explore the key considerations publishers need to make when evaluating their consumer revenue strategies. We walk through how some major companies have thought through their strategies, thinking through content strategy, measuring success, distribution issues, and product strategies. The publications profiled in the document have different business models, different resources, and different structures. Their approaches are presented not as prescriptions but as ways to help think about reader revenue and where it might fit into your organization.

Digiday members can access the full guide, including charts and data, below.

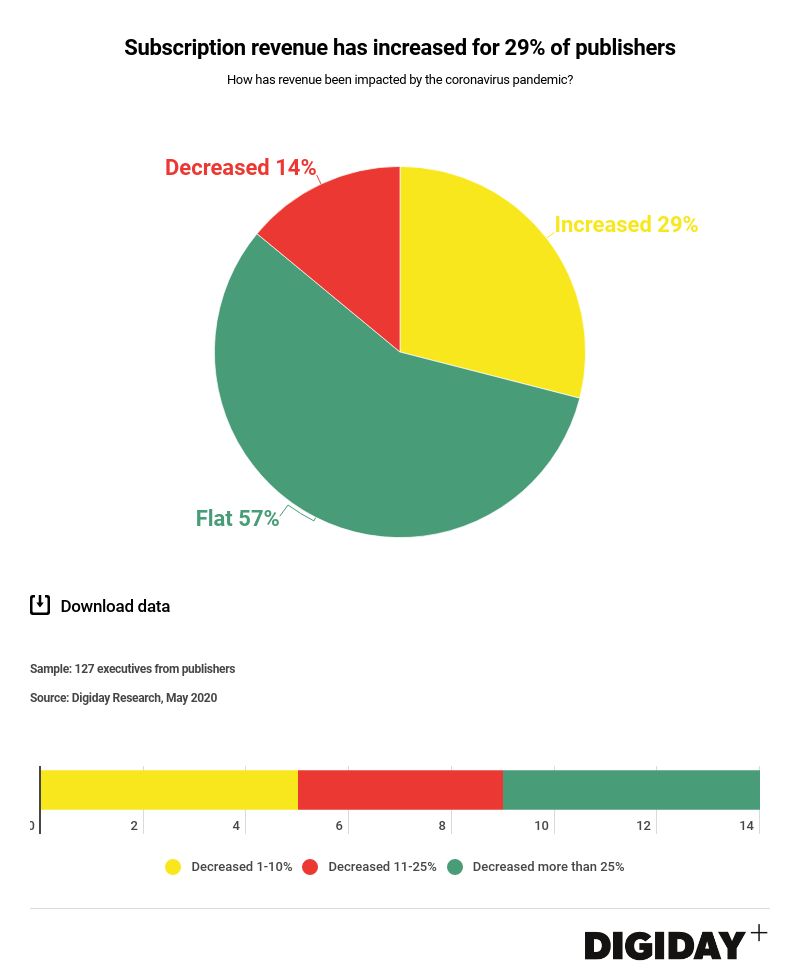

The current crisis makes subs even more of a priority for many. Digiday Research found that in the first quarter, ad revenue was hardest hit, decreasing for a whopping 65% of all publishers. This included direct sold and programmatic ad revenue. But subscriptions were a bright spot. Subscriptions actually increased for 29% of publishers, and decreased for only 14% of publishers. For 57%, they stayed flat.

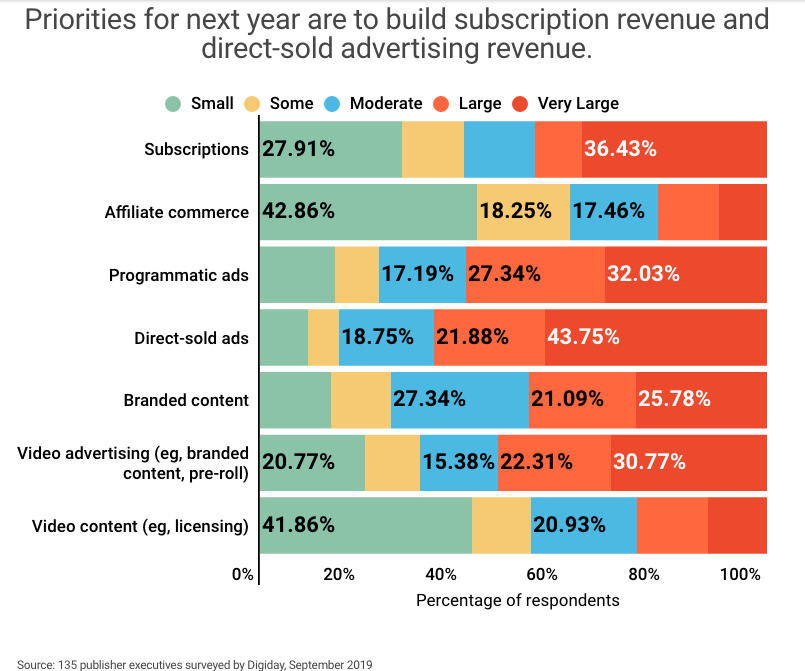

In a survey of 135 publishers conducted by Digiday Research last fall, almost 46% of respondents said growing subscriptions were a major focus for them over the next six months. Other major priorities are building direct-sold ads: 64% of publishers said that was either a large focus or a very large focus area for them.

Neither comes as much of a surprise. Subscriptions are an important and controllable way to generate revenue. Sometimes that even comes at a lower resource allocation cost — Digiday Research conducted last year found that 75% of publishers surveyed allocated less than 25% of their company’s resources to subscription products. In an increasingly unstable digital advertiser landscape, any way to have sustainable revenue streams is a priority.

Unlike other revenue diversification plays like branded content, or commerce, or events, subscription and membership products require different skillsets, attitudes and strategy.

Editorial teams conditioned to maximize page-views have to learn how to maximize returning visits, or subscriber conversions. Product teams that built sites optimized for revenue per visitor need to start thinking about customer lifetime value instead. Ad sales leaders, long accustomed to setting the agenda for the revenue side of the business, have to balance their priorities with the needs of membership editors.

“You have to really commit,” said Mary Walter-Brown, the cofounder of News Revenue Hub, a membership organization that helps news publishers build reader revenue. “It’s not something you dip a toe in. You have to have this ongoing communication with your audience, and you have to commit to it.”

In some ways, today’s adverse conditions offer a great time to figure out subscriptions. With CPMs down and engagement at or near all-time highs for many publishers, “it’s never been cheaper to invest in the long-term,” Slate CEO Dan Check said. “So we’re shifting focus to long-term value.”

For most of its history, Slate envisioned its six-year old membership program, Slate Plus, as a source of incremental revenue; as of last year, it had over 50,000 members paying up to $59 per year.

“You have to really commit.”

Mary Walter-Brown, the cofounder of News Revenue Hub

But last year, Check decided Slate would start going after members more aggressively. In late March, Slate put up a metered paywall, with the goal of converting more of the site’s most avid readers into members. (Prior to the paywall, more than 70% of Slate Plus members had converted through the publisher’s podcasts).

Check said he expects Slate Plus to grow into 20% of Slate’s revenue next year. But he has no plans to add more features to the product or to pivot the business model away from its current focus.

“We still see [advertising] as a good long-term business for us,” Check said, noting that Slate’s ad business grew by double digits in 2019. “But we do think you need to supplement it with something else.”

For others, the current advertising crunch validates the thesis that reader revenue has to be the north star.

Quartz had already begun shedding roles in its advertising and consolidating around its subscription business last year, which had around 18,000 paying members at the end of 2019, according to quarterly earnings.

But the shock of its ad revenue dropping 54% year over year in the first quarter of 2020, part of a first quarter in which Quartz lost $6.3 million, reinforced the necessity of growing a base of recurring revenue.

“It’s hard enough to do one thing well,” Quartz CEO Zach Seward said. When Quartz was getting its membership off the ground, it had separate teams of people in editorial, product and marketing all working on the program.

Ultimately, the mindset needed to pursue reader revenue might be more important than how big a slice of pie that revenue represents. Before New York Media merged with Vox Media, the goal at New York had been to diversify to the point where advertising constituted less than 50% of its total revenue, with a combination of subscriptions, commerce, brand licensing, film and TV and events making up the rest, said Daniel Hallac, who served as New York Media’s chief product officer at the time.

“It’s hard enough to do one thing well.”

Zach Seward, CEO, Quartz

“I think there’s a transition in the industry, where we’re moving from a content-centric model to a user-centric model,” said Hallac, who now serves as svp of consumer products at Vox Media.

Hallac said that same mindset will guide the development of a membership product for Vox Media, which rolled out a voluntary donation offering just as the pandemic was beginning to spread. The goal is to eventually turn that into a fully formed membership program, Hallac said, though there is no set roadmap for how it will get there. It plans to follow what readers want, and act accordingly.

“We said, ‘Before we go and spend months of resources building a full-blown solution, doing market research, all of that, let’s just get it on the site and keep learning,’” Hallac said. ““It was like, ‘There’s an opportunity to do this now.’“

A new way of working

Creating content for a mass audience is different from creating content for a niche audience. Instead of riding trending topics on CrowdTangle or producing quick hit summaries of movie trailers, looking for more ways to generate more content for a lower price, subscription-focused publishers need to do the opposite.

A subscription-focused newsroom pays attention to what its most devoted visitors read, what kinds of stories get a reader interested in one kind of content interested in another; what kinds of stories get a reader to subscribe to a newsletter, and then another.

Focusing on those priorities also requires collaboration and communication across departments including product, business and analytics, usually more than newsrooms are used to. At the Seattle Times, leadership introduced this new way of working one handful of reporters at a time, connecting the teams that wrote about one specific topic, such as the University of Washington’s football team, to product and business-side colleagues who helped the reporters and editors dig more deeply into what the Times’s audience was reading at standing, regular meetings.

- The meetings were designed to help the reporters understand data better, but also to help them to figure out new products or strategies that could help the Times drive more subscriptions. Some reporting teams created pop-up, seasonal newsletters; others created blogs. The changes were led by what the audience responded to best.

- Just getting to that point of building those teams took years for the Seattle Times. About two years prior, it built an internal dashboard that showed the newsroom which stories were driving subscriptions.

- Writers and editors have a reputation for being intransigent, but they can be receptive to change if the reasons for it are clearly explained. Before the Dallas Morning News began laying out plans to focus on subscriber growth, it circulated memos in the newsroom explaining what was happening in the digital advertising ecosystem, right down to declines in CPMs, as a way to make the case that subscriptions were a more promising strategy than advertising was.

A new way of measuring success

This year, the reporters at Tribune Publishing titles will all get access to a dashboard licensed from the American Press Institute, which shows reporters how many existing subscribers read their stories and how many subscriptions it drove, in addition to the pageviews.

- Like the dashboard the Seattle Times built, the dashboard is designed to get reporters to think differently about the impact their work has. Over time, it could be used to set subscriber targets for the reporters, but there is no timetable for doing so.

- Setting subscriber goals is an important, but fraught step in pursuing a subscription strategy. While publishers such as Business Insider dole out bonuses based partly on how many subscriptions their work drove, others set non-binding growth targets for their reporters instead. The targets are non-binding partly because most newsrooms are still getting used to the idea (and partly because a binding target might run afoul of a newsroom union contract).

- There is also no consensus on how to decide whether a story led to someone subscribing. Some publishers give stories a certain amount of credit depending on how many days pass between the story being read and a subscription occurring; others give all the credit to whichever exclusive story someone signed up to read.

Read more: The coronavirus has meant a real opportunity for publishers to gain (and keep) subscribers.

For an ad-supported publication, the goal of distribution is simple: Secure the largest possible top-line audience for the lowest possible cost. For a subscription-focused publication, the priorities are a bit more complicated.

While some amount of low-cost, scaled audience is needed, distribution strategies for subscription publishers tend to be shaped by user journeys. Very few subscribers will get out their credit cards the first time they are asked to pay for content, so publishers need to understand where their subscribers read their content, what brings them to their site, what kinds of content typically compels people to convert, then distribute accordingly. If a person won’t pay the first time, the goal is to put that person in position where they’ll hit the paywall again and again until they do.

Some of that work happens on social platforms like Facebook, where publishers such as the Wall Street Journal spend money to distribute stories that came up most often in subscribers’ user journeys. It also happens on Snapchat, where The Economist fills the top of its funnel with readers who may not subscribe for a long time.

Which platform a publisher uses to distribute something partly depends on the role that content is likely to play in a subscriber’s journey. The Minneapolis Star-Tribune, for example, puts stories that led to the greatest number of subscriber conversions in its recirculation widgets for registered readers.

But some of the most crucial distribution decisions are made before a story even hits a website. Subscriber-exclusive content can be a powerful way to drive subscriber growth, but it can also mean one less story to distribute to potential subscribers. Many publishers that choose to make select content exclusive to paid members will begin by not putting enough behind a paywall, then slowly ramp up. The Daily Beast, for example, recently drove a 100% increase in membership signups partly by increasing the amount of content it made exclusive to members.

Video

The economics of ad-supported video have challenged publishers for years, and

the economics of video for subscriptions can seem even more daunting. Instead

of distributing the video across multiple ad-supported platforms and websites

and hoping to cobble together a profit, a subscription publisher has to deliver

a high quality product to a much smaller audience, then try to figure out whether

the investment was worth it:

Are the videos a good investment if they lead people to convert? Are they a good investment if they retain subscribers and reduce churn? Are the videos doing one, or the other? Both? Which is a better investment?

These questions help explain why few publishers have made exclusive videos part of their subscription products. But a handful have.

- Quartz, for example, has concluded that high-end, exclusive video content can motivate people to subscribe – it is the second most effective driver of subscriber conversions, after in-depth guides that its reporters typically spend more than a month producing. The publication’s team uses data about what its audience reads and engages with the most on its site to guide its video strategy, hoping to lead more people to its paywall.

- By contrast, Architectural Digest has decided to treat video as a supplementary element of its B2B subscription product, AD Pro. Subscribers get a couple of in-depth videos every month, and AD keeps costs low by sending crews to locations where its ad-supported video content shoots are already underway.

- When it comes to driving subscriptions, email is king. Publishers use email in a variety of ways, either to market via offers to people already in their databases (at the top of the funnel) or to market specific types of content to specific segments.

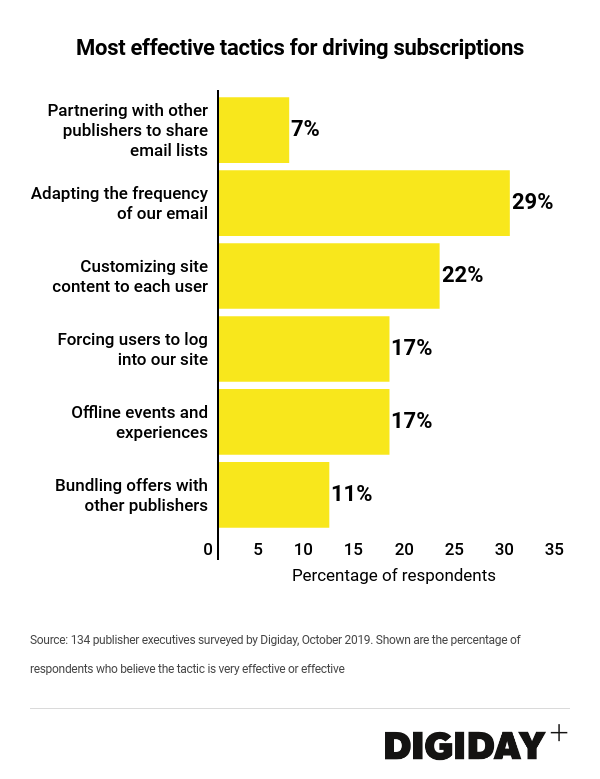

- Digiday research conducted last year found email — specifically, adapting the frequency of email, to be the most effective tactic.

- Second was “customizing content” for users while tactics like bundling weren’t that popular.

In the old days of print media, consumer revenue was pretty easy to figure out. If somebody wanted to read a magazine or a newspaper’s contents, they had to pay for it.

Digital media offers more flexibility (and complexity). While many publishers use a simple paywall as the foundation, others have found success disaggregating their content, bundling it with services, or making community interaction the selling point. A user-centric approach is the common thread through all of these approaches.

Disaggregation

Just as publications sell different parts of their content to different kinds of advertisers, that same content can be packaged and sold directly to readers in different combinations. Newspaper publishers including McClatchy, Hearst, and the Dallas Morning News offer standalone subscriptions to their local sports coverage. The sports subscriptions cost less than a regular newspaper subscription but boast strong retention (and attract subscribers no longer living in the newspaper’s geographic area). In a similar vein, Vice built a freemium astrology app that has been downloaded over 100,000 times.

The finer one slices one’s content, however, the lower the ceiling gets for a product. Esquire, for example, sells a “micro-membership” around one of its best-known writers, the politics blogger Charles Pierce. Over 10,000 people pay $17.99 per year to get unlimited access to Pierce’s work, as well as an exclusive newsletter and a tote bag. It would be hard to charge much more for a portion of content available on a site with no paywall, as well as a physical magazine whose subscriptions can be had for not much more.

Bundling

After a publication has converted as many subscribers as it

can using its core product, many will turn to bundles as a way of luring in a

second, incremental tranche of customers. Those customers typically generate

less revenue per user than a core subscriber, but they make up for it with scale.

They also create an interesting marketing puzzle. What kind of content or services complements a publication’s core offering?

Bundles can include services as well as content. The New York Times has experimented with subscription bundles that include Spotify and Scribd, while TechCrunch has rolled a collection of paid perks, such as 12 months of free cloud storage and early access to its events into its membership product, Extra Crunch.

Some bundles can be bespoke, or temporary. The New Yorker, for example, will temporarily add its content to a bundle like Apple News+ by windowing the print editions of their magazines, both to maximize its value while exposing it to multiple audiences at the same time.

Membership

or subscription?

While access to content is typically sold as a subscription, many publications

have styled their consumer revenue products as memberships, a distinction that

quickly becomes meaningful the more you think about it.

After testing out a membership product, The Masthead, in 2018, The Atlantic decided to reframe its paid digital offering as a subscription in 2020, in part because it decided not to build the infrastructure needed to support the continuous exchange it decided it would need to offer as part of a membership; Atlantic president Michael Finnegan told Digiday he wanted to clearly communicate to readers that they were paying for access, rather than entry into a kind of club or community.

By contrast, some publications frame their products as memberships because they see them as ways to deepen the connections they have to their most passionate readers. Samantha Henig, the executive editor of BuzzFeed News, said that while direct revenue is important, the goal of BuzFeed News’s membership program, which accounts for less than 10% of revenue, is to establish a direct line of communication with the people who are the biggest fans of the nascent brand.

Digital publishers are forced to constantly refresh their skills and talent to keep up with quick changes in the space. And many publications with legacy print businesses have the infrastructure needed to do some consumer marketing. But pursuing digital subscription revenue requires an entirely different base of skills, many of which are not native to media as an industry.

Publishers planning a move into consumer revenue may have to either add new executive leadership, or prepare to have them learn some new tricks.

The New CMO

At one time, the CMO role at most media companies was a quasi-B2B communications role, focused on the needs of a small audience: The leaders at top advertisers, trade groups and platforms.

The CMO of a modern publisher pursuing subscription revenue is focused on a much bigger audience, and their priorities are very different: Efficiently deploying resources to acquire – and keep – subscribers.

- Finding that skillset can be tough. Over the past two years, a number of large news organizations, including the Washington Post, Hearst Newspapers and The New York Times have added new CMOs, in Hearst and WaPo’s case, for the first time. Others, such as USA Today, have changed theirs, with the new hires bringing skillsets that reflect these changing priorities.

- Rather than working mostly with the sales and marketing teams, the CMO of a publisher pursuing subscribers has to work closely with product, editorial and finance to ensure that everybody is aligned around similar goals. A strong focus on customer acquisition, analytics and retention are essential.

- Like their counterparts at brands, the subscriber-focused CMO is beholden to lots of his colleagues in the C-suite: To heads of content or editors in chief, who figure out what kinds of content to produce for an audience, or the chief product officer, who figures out what an audience wants and guides the publisher’s teams in that direction.

The

New Audience Development Team

At one time, “audience development” was code for “audience growth.” Though the

tools used to drive that growth differed – some relied on Google or Facebook,

others on email – the top priority for audience teams tended to be growing the

scale of a publisher’s audience, regardless of quality.

- For publishers focused on subscriptions, the platforms and the tools remain largely the same, but the priorities are different. Today, audience development teams at publications including the Boston Globe also have to focus on deepening the relationship readers have to their brands: Driving more newsletter signups, boosting time spent on site, or figuring out which segment of an audience should see a promotional offer for the brand’s newest subscription product.

- Audience development roles are often situated in the newsroom, which can make the emphasis on revenue feel uncomfortable at times. But driving subscriber growth requires editorial teams to work more closely with other parts of a publisher’s organization.

Growth

Marketers

While audience development has historically focused on driving organic

engagement and growth, some publishers have invested in growth marketers to

augment the audience development team’s work with paid promotion.

- Publications including The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal have large teams whose job it is to drive paid promotion of their subscription products, but smaller publications have begun hiring for the job too.

- Hiring for those roles assures that digital marketing budgets are spent more effectively. But they also give publishers, who typically used marketing for different purposes, the expertise necessary to communicate with subscribers off-platform in ways that keep them engaged and retained. And to find them, publishers have been forced to hunt for talent not just at agencies but at DTC brands and their competitors.

Product

Managers

Subscriptions typically require significant amounts of ongoing collaboration

across product, editorial and marketing. That, in turn, creates a need for

product managers, who can keep disparate parts of an organization aligned while

pursuing various strategic goals.

- The Washington Post has tripled the number the number of product managers it employs over the past three years, while publications including Vox Media and Bloomberg Media have been snapping them up as well.

- But product managers also pose thorny problems for publishers. They create organizational headaches and upset power dynamics; they can be difficult to find and keep; and they force publishers to reckon fully with just how committed they are to acting like the owners of digital products, rather than the producers of content.

Membership Editors

Publications ranging from BuzzFeed to HuffPost to The Intercept have sought to hire membership editors, a job whose responsibilities differ from place to place. Some see growth hacking as an integral role; some see editorial experimentation and product development as more important.

- The responsibilities for these roles differ significantly. The HuffPost listing, for a “deputy managing editor of membership and innovation,” called for someone who can create new engagement and messaging strategies, while Quartz’s deputy membership editor listing focused on identifying “creative and compelling editorial approaches for paying readers”; listings posted by BuzzFeed and the Intercept list driving membership growth as a key priority.

- But there are some commonalities: connecting with product, marketing and editorial colleagues, messaging and distribution and marketing membership products.

- But the balance between those tasks varies widely, illustrating how nascent membership operations are at most media companies.

Finding talent can be difficult

Hiring new talent is a challenge for the vast majority — 71% — of publishing executives surveyed by Digiday. But the hardest roles to hire for aren’t in editorial — they’re in product.

- Digiday Research surveyed 134 publisher executives to ask them about what in terms of talent management they’re finding hard, and the roles they find it especially hard to recruit for.

- Digiday Research also asked what type of talent was the most important one that publishers were looking to hire in the coming year. The most important one: product developers and product managers. Fifty-eight percent of respondents said that hiring product developers and managers was very important or important.

Churn

The rate at which paid customers cancel or don’t renew their subscriptions.

Unlike some other media statistics, there is no universally agreed-upon way to

calculate churn, since it can be measured different time periods, such as

monthly or yearly. That makes churn tough to talk about, though it is generally

accepted that high-priced products should have lower churn than more affordable

ones: In theory, a higher priced product delivers more value to a smaller audience.

ARPU

An acronym for “average revenue per user.” ARPU is the number that allows a publication to consider the amount of money, be it in the form of ad revenue generated or subscription revenue, that an average reader brings in.

LTV

Lifetime value, the amount of revenue a publisher expects to earn each time it

acquires a subscriber. Though it takes several months – at least – to set LTV

on a product, it can become the lens that publishers view every product

decision through.

Rather than thinking about maximizing the revenue a publisher might get out of a person’s single visit to their website, LTV shifts the focus to the amount of money the publisher might earn from years of subscriber visits. That focus has helped some publishers consider ideas ad-free experiences for subscribers.

MRR

Monthly recurring revenue, a number that summarizes how much money a publication’s subscription product delivers every month. This is the number that communicates most clearly why consumer revenue is so attractive to media companies.

Inside the Daily Beast’s ‘corona bump’

While making coronavirus coverage free, publishers face a trade-off

Publishers should think like gyms

Publishers’ biggest subscriptions challenges in five charts

This story initially said Dan Check of Slate expects Slate Plus to grow into 20% of Slate’s revenue this year. In fact, it’ll be next year. Slate Plus now has more than 50,000 subscribers. The story has been updated to clarify.