Secure your place at the Digiday Publishing Summit in Vail, March 23-25

‘We’re at the foothills of what we can do’: How The Guardian improbably put itself on the path to profits

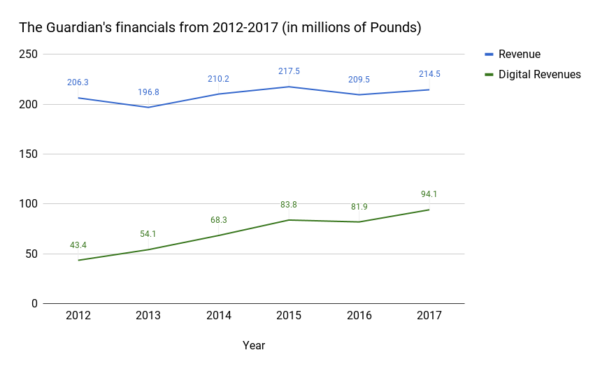

After two battle-weary years in which The Guardian cut costs and halved losses, the publisher is starting to turn a corner. Today, it has a new reader-revenue driven business model and is on the brink of breaking even.

Getting to this point hasn’t been easy. The Guardian has been forced to downsize and rein in its global ambitions. But a shift to a unique reader revenue model that relies on voluntary contributions as opposed to restricting access has, in many ways, proved naysayers wrong.

Today, The Guardian, coming off a redesign, can confidently say it is on firmer footing than it has been in years. The Guardian has halved its operating losses compared to two years ago, now looking at breaking even by 2019. Perhaps most critically, it no longer relies on advertising for the majority of its revenue. In recognition of its comeback, The Guardian was named publisher of the year at the Digiday Awards Europe on Jan. 24.

“We’re making great progress with our three-year strategy and on track to break even by 2019,” said Guardian Media Group CEO David Pemsel. “The media sector remains challenging. However, our reader revenues are growing well, our advertising proposition remains strong, and more people are reading us than ever before. We now reach over 150 million unique browsers each month and we have over 800,000 supporters.”

No longer chasing reach

When Pemsel and editor-in-chief Katharine Viner laid out their three-year cost-cutting plan in 2016, weaning itself off chasing reach was the top priority. The Guardian’s mantra of open journalism naturally lends itself to big audience numbers, with the publisher attracting 23 million monthly unique users in the U.K. and 31 million in the U.S., according to comScore. But as many publishers have found, big audience numbers don’t necessarily equate to revenue — a fact the Guardian has been candid about from the start.

“One of the core parts of this three-year plan was to build deeper relationships with our readers and not be so obsessed about reach,” Pemsel said in an interview with Digiday.

Where others like The New York Times and The New Yorker have turned to the trusty paywall, the Guardian took a philanthropic route, asking readers for one-off donations and paid memberships. So far, that decision is paying off.

A total of 800,000 people now pay money to the Guardian, 300,000 of which are regular paying members, up from 50,000 two years ago, when it started offering paid memberships. An additional 200,000 subscribe to the digital and print editions and readers have made 300,000 one-off contributions, according to the publisher.

“The Guardian has undoubtedly exceeded everyone’s expectations,” said Alice Pickthall, media analyst at Enders Analysis. “In the long term, they need to find more ways to monetize their audience than just charity, but committed digital subscribers, not just supporters.”

The publisher has experimented with using data to see what topics people are most interested in, then solicited donations around related events and coverage. That approach has worked particularly well in the U.S.

“The U.S. market is very different in terms of people’s propensity to contribute, so we’re no longer just beholden on advertising there,” Pemsel said. “We’re at the foothills of what we can do [with donations and paying members], and we’ll keep testing and learning our way through generic and topic-specific contributions.”

Reining in costs

Journalism faces a cost problem. The revenue-per-reader in advertising is a fraction of what it is in print. That’s led to a reckoning that news publishers can no longer try to do it all.

Naturally, cost-cutting across the board has been front and center of the Guardian’s pivot to building a sustainable business model. The publisher’s pledge to cut 20 percent of its costs within three years, began with scrapping plans to transform the 30,000 square foot Midlands Goods Shed (a former train depot) at King’s Cross into a dedicated events space. Guardian Media Group also sold its 22.4 percent stake in Cannes Lions owner Ascential for a total of £239 million ($339 million.) Another wave of cost savings were made from job cuts, 400 in total, leaving the current staff count at 1,500 people.

The publisher then started looking at where it could cut back overseas, specifically in the U.S. Last year the Guardian’s U.S. offshoot underwent a severe course correction. After a buoyant U.S. launch in 2014, the publisher was forced to cut 60 staffers; the head count now stands at 80. The publisher reduced office space costs as well, relocating employees to a WeWork office in New York City. A core reason for the heavy trimming: The U.S. edition was set up to be mainly ad-driven. The U.S. operation brought in $15.5 million in revenue in the year ending April 2016, only to lose $16 million. This year, the U.S. office will make “a positive contribution” to the Guardian’s profits, according to Pemsel.

“However difficult it was [making cuts], the U.S. remains an incredibly important part of The Guardian, both editorially and commercially,” said Pemsel. “It’s just that it was being built primarily at the time for an advertising-only outcome, and the dramatic changes happening in the U.S. market around digital advertising meant it was just not sustainable within the financial framework we had set.”

Last January, Evelyn Webster was appointed interim CEO of Guardian U.S. She oversaw big internal changes and the diversification of revenue streams with reader revenue. Of the 300,000 one-off contributions made to The Guardian, half of them came from the U.S. Its biggest day for U.S. contributions was Donald Trump’s inauguration, according to the publisher.

As many publishers have found, the days of spending millions to expand into a new market and hoping they deliver a return through advertising alone are probably over. They certainly are for the Guardian, which instead is more interested in putting relatively small, agile teams into new markets and seeing if readers can fund them, according to Pemsel.

This has come with other cuts, of course. Last week, the Guardian shrunk its print edition from the Berliner format to a slimline tabloid and outsourced the printing and distribution of the paper to Trinity Mirror Group. That will shave “several million” off its cost base, according to the publisher.

Taking a stand

Despite its focus on reader revenue, advertising remains core to the business, and the Guardian has cracked down on bad practices, particularly in programmatic advertising. It remains the only publisher to take a serious stand against an ad tech vendor over hidden tech fees, and its lawsuit against Rubicon Project is ongoing. But it has also called for more industrywide action to tackle fraud in digital advertising. Now, it is using data to identify high-value buyers in the open market and switch them to premium programmatic. The publisher claims this tactic has grown yields while ensuring more of advertisers’ dollars go to working media.

Agencies are bullish on the Guardian’s ability to retain high-quality services to them, despite the job cuts. “When a company that large is going through such massive change, you will inevitably see a drop-off in servicing,” said Craig Smith, trading director at media agency Mindshare. “But to their credit, we never saw anything like that, despite the fact it was probably a tumultuous time as a business in terms of how they dealt with us.”

The Guardian has also overhauled its commercial structure and external messaging in the last two years, positioning itself as a “platform for change” that will deliver meaningful business results for advertisers, not vanity metrics like click-through rates. That clarity of message, along with its success with reader revenue, puts it at the top of the list for agencies, Smith said.

The publisher has also revamped its branded content operation, Guardian Labs, in the past year. The former in-house agency model has been dropped in favor of a commercial features desk led by new executive editor Imogen Fox. As a result, its win rates on briefs have doubled, according to the publisher.

Keeping up culturally

The Guardian operates differently today than two years ago. Of course, it’s smaller, having reduced its head count by 400 people to around 1,500 during that time. But beyond that, the Guardian has implemented in the last few years a process to get departments to collaborate with each other and ensure its products evolve faster — a departure from its formerly siloed structure, similar to many legacy businesses.

Dozens of cross-department huddles occur each month, with people from commercial, editorial, product, marketing, engineering and user experience meeting with a set problem to solve. Every three months, they give progress updates. The process, borrowed from Google, has been instrumental in shaping the Guardian’s current model. The idea of asking for donations as an alternative to a paywall came from one of these huddles, for example.

In addition to those moves, the Guardian has also invested £42 million ($59 million) in venture capital fund GMG Ventures to stay abreast of technologies like artificial intelligence that are set to change news distribution.

More in Media

How medical creator Nick Norwitz grew his Substack paid subscribers from 900 to 5,200 within 8 months

Creator Playbook: Unpacking the strategy behind medical YouTuber Nick Norwitz turning to Substack to significantly grow his brand.

Media Briefing: In the AI era, subscribers are the real prize — and the Telegraph proves it

In an era where AI is eroding referral traffic and third-party distribution, a subscriber who pays directly has become the most valuable reader a publisher can own. Springer just bought over a million of them.

Layoffs hit LADbible Group’s social video team amid slower user-generated content growth

Social-first publisher LADbible is in the middle of a second round of layoffs to its social video team, having suffered massive drop-off in Facebook video engagement.