This research is based on unique data collected from our proprietary audience of publisher, agency, brand and tech insiders. It’s available to Digiday+ members. More from the series →

The death of the third-party cookie is fast approaching, and the industry can see the end of the road when it comes to their ability to buy and sell ads that use individualized targeting.

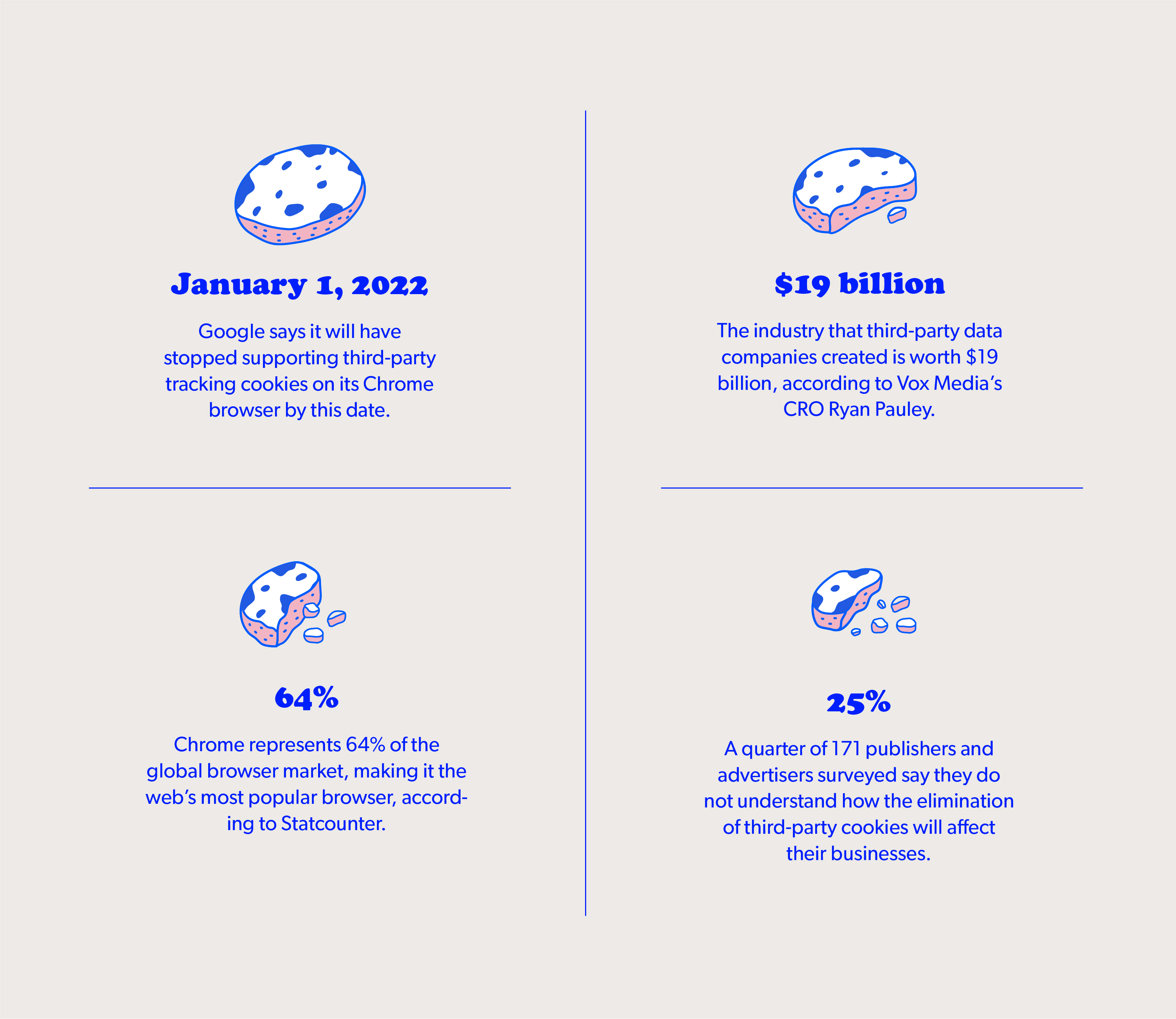

Google announced in January this year that by 2022, Chrome would no longer support the use of third-party cookies. Other browsers — Mozilla’s Firefox and Apple’s Safari — have already removed third-party cookies and national and local governments have enacted privacy laws to regulate the collection, use and sharing of online identifiers. But Chrome is the most popular browser, making this move for many really the nail in the coffin.

The move, Google said, is designed to encourage publishers, advertisers and others help Google create a new set of privacy-focused open web standards.

Still, publishers and marketers remain in the dark about how this will impact their businesses.

Here’s Digiday’s primer on all you need to know about life after the third-party cookie.

When Google announced that it was taking third-party cookies off of its Chrome browser in January — following the changes towards privacy that Apple’s Safari and Mozilla’s Firefox browsers have made in the past few years — publishers and marketers said the writing had been on the wall for years.

Google says that the end of the cookie will make web browsing more secure for users. But the proposed shift is likely to send tremors across an entire online ad ecosystem that has long relied on cookies to target and track advertising.

Third-party cookies have been in use for over 10 years. The data they store drives a $19 billion industry, according to Vox Media CRO Ryan Pauley, making it “a crutch in the industry for a long time.” Having the ability to target consumers on a personalized level has remained a solution that not many in the industry were rushing to replace because the multi-touch attribution it delivers across sites provides marketers with an abundance of audience information.

“A crutch in the industry for a long time.”

Ryan Pauley, CRO, Vox Media

Despite a race to the bottom in terms of how cheap this advertising can get, publishers have been following the money for years.

“We have taken what the third-party cookie was meant to be and stretched it to its brink,” said Krystal Olivieri, svp of global data strategy and partnerships at GroupM, continuing that it enables marketers to get down to the one-to-one level in a way that no other channel — like television or out-of-home — has ever been able to do.

A solid replacement, or even a set of technical standards for how media companies label their first-party audience data that they deliver to marketers, however, has not yet to come into the picture for when the cookie finally crumbles.

With the loss of the third-party cookie will come a reset of the industry that might lose individual targeting abilities, but she said she believes that “advertisers will be able to adapt and restructure around that.”

“Stretched it to its brink.”

Krystal Olivieri, svp, global data strategy and partnerships, GroupM

Most of the key players in the media-advertising ecosystem are actively looking for or building their own “solutions” to losing the third-party cookie. Even the browsers themselves are trying to contribute a method of keeping data collection within their platform, for example, Google’s Privacy Sandbox initiative.

“What remains to be seen is whether or not [one solution is] uniformly adopted by the browsers,” said Jordan Mitchell, svp of privacy, identity and data at IAB Tech Lab. If not, “then they aren’t standards.”

The IAB Tech Lab is one organization that is in a dash to create and implement its technical standardization plan. The timeline that Mitchell said his team is on is to have it completed by the first quarter of 2021, which seems extremely soon, given the turbulence that the industry is facing with the pandemic. Mitchell argued, however, that, “It’s this year or it’s a failure. We have to be very aggressive because losing out on cookies without a suitable replacement makes for two really awful years instead of one year for the industry.”

Some are concerned that private platforms like Facebook and Google will get even more of the ad spend because marketers will not be satisfied with the decrease in individual data that publishers can provide. Facebook will also be impacted by this change, however, with the pixels it uses to collect transactional data. It, too, will be forced to rely on behavioral data from its users.

“I believe this brings a huge opportunity to the independent publisher market to grab back market share from Facebook.”

Nick Halstead, CEO of Infosum

Publishers individually have an opportunity to capitalize on the disappearance of the third-party cookie and coalescing first-party reader data into one platform that they can then use to appeal to marketers. Insider, Vox and Meredith have all spent the past couple of years developing these platforms, which focus on contextualizing each page’s content and sentiment.

In tests, publishers report that ad campaigns produced using first-party data are gaining upwards of a 50% to a 100% better performance on certain key advertising metrics versus similar campaigns that still use the third-party cookie data.

The issue with publishers building these individual data solutions is that it creates a “walled garden effect,” which Olivieri said limits the ability for marketers to understand audiences from publisher to publisher. “We can’t compare those audiences” and know things like if marketers are over-serving the same ads to certain audiences.

“We like easy ways of buying,” said Andrew Goode, evp of programmatic, North America at Havas Media Group. “Going from silo to silo breaks that down and we lose the ability to measure like to like.”

It is imperative that the industry figure out a standardization solution that will create a common language around data that marketers can understand from publisher to publisher.

Contextual targeting and using first-party data

Publishers like Insider, Meredith and Vox have built first-party databases that rely on a taxonomy of terms to help contextualize each page that they publish. This will not only help to categorize the actual content, but it can highlight the purpose of why a reader came to the page in the first place, showing intention.

- “Context is going to be important going forward,” said Chip Schenck, Chip Schenck, svp of data and programmatic solutions at Meredith. “It will be harder to do with programmatic, we want to not only know the words but the purpose of reading.

- Contextual targeting works. Insider reports that one of their clients who ran part of a campaign through its Saga data platform shared an 11% performance improvement over the segments with third-party cookies.

- Vox’s Forte platform has also run campaign tests alongside their third-party cookie campaigns and noted a 50% to 100% lift on key ad metrics.

Programmatic is a top revenue driver

Of 187 publishers that Digiday surveyed in November 2018, 55% said that programmatic advertising was their largest driver of ad revenue, while 23% said private marketplaces or programmatic direct or guaranteed deals specifically are their biggest sources of ad revenue.

In March this year, programmatic ads were a major or moderate source of revenue for 57% of publishers. And 55% of publishers said they would prioritize programmatic ads over the next quarter.

Therefore, it is important to modify your business to keep this line of revenue in the mix.

- For small- to mid-sized publishers that don’t have the means or wherewithal to build there own database, there are many third-party vendors and publishers who are licensing their tech stack to be able to create their own taxonomies to have that contextual tracking piece.

- In a survey of 135 publishers conducted by Digiday Research, coming into this year, programmatic tied for third in the rankings for publishers’ (who earn $50 million or more in revenue) biggest priorities heading into 2020. For publishers earning under $50 million, programmatic jumped up to be the second most prioritized area of business this year.

- And in a Digiday survey polling 103 European publishing executives in February 2019, 25% said they saw programmatic revenues increase since GDPR was enacted in May 2018, while 17% reported a decrease. Meanwhile, 58% of respondents said their programmatic revenues have remained unchanged.

One of the groups that’s most affected are retailers. Third-party cookies help retailers figure out when to serve an ad to various groups of users, a tactic the industry has relied on heavily. (Remember the “boots that followed you around the Web?”)

Retailers may also rely on vendors who use third-party cookies to offer certain experiences on their website that they don’t want to build themselves. Jason Goldberg, chief commerce officer for Publicis, gave the example of a retailer integrating a third-party chat service into its website. The chat service may use a third-party cookie so that it can understand what products a customer was looking at on that retailer’s page, when that customer then visits the chat service for assistance.

“If you go to almost any e-commerce site, and you look behind the seams, what you are going to find on average is that [the] e-commerce site is relying on 38 different web addresses to build that e-commerce page,” Goldberg said. “Some of those 38 are owned by the retailer, but many of those 38 are vendors that the retailer has partnered with to provide various services, and any one of those external partners may be today relying on third party cookies to partly fulfill that service.”

One solution will be first-party data gathered by retailers. Ad tech firm Criteo, for example launched a retail media solution in 2018 that the company has said was “designed to be largely immune against third-party cookie restriction,” by working more closely with retailers to gather first-party data to use for targeting. First-party data means any data that a customer gave a retailer or brand such as email address, or information gleaned from their past purchase history.

Biggest concerns

In a January 2020 survey of 84 buy-side advertising execs, 76% said they are worried about their ability to target and measure ads after third-party cookies are phased out. This is compared to 54% of 87 publishing execs who said they are worried about ad targeting and 58% who are worried about measuring ads.

- “I think one of the key things I’m worried about is that there is no standardized framework to approach,” said Group M’s Krystal Olivieri. “Where my concern lies is that if we’re understanding an audience on publisher A well and publisher B’s audience well, but we can’t compare those audiences” then marketers are left not knowing if they are hitting a lot of people, the same people or potentially inundating those audiences with the same ad.

- Not all marketers share the same concerns. “I don’t see this being an existential threat to the digital environment. It’s about implementing a different way of working and I don’t think we’ll be unable to do our jobs,” said Havas Media’s Andrew Goode. “We do run the risk of compartmentalizing the industry.”

Collecting granular data in the new world

Advertisers are in a bind: They need to find ways to replace the granular audience data they acquire from third-party cookies in order to continue to hit their monthly marketing targets. To do this, they are are going back to old-school measurement methods like surveys and panels as well as using publishing partners to provide more insights into their campaign performance.

- “These types of studies are hard to do … most companies still don’t have a multi-touchpoint attribution system in place,” said Bedir Aydemir, head of audience and data, commercial, at News UK.

- Because of that, advertisers are increasingly demanding publishers for more brand-uplift studies, which measure digital ad campaigns using first-party data. This helps to alleviate some of the burden from marketers.

- Brand-uplift studies identify changes in metrics like brand awareness, consideration, favorability and intent to purchase and show campaign effectiveness beyond performance.

What marketers need from publisher first-party data

Contextual and behavioral data can help to illuminate publishers’ audiences’ consumption habits and make their interests and intentions more clearly known, just as well as third-party cookies, in some cases. But as Olivieri mentioned earlier, there are issues with translating that data from publisher to publisher, putting a lot of the workload back on the marketer.

- IAB Tech Lab is working on its Rearc initiative, which will consist of a playbook of technical standards for how data is communicated across the internet. There are hesitancies around this, however, mainly about whether or not it will be completed by the time the third-party cookie has vanished and whether or not there will be universal adoption.

- The resurgence of publisher alliances like Ozone alongside the rise of advertiser-controlled marketplaces that are all pitched as privacy-first solutions that can offer alternatives to the third-party cookies that are being prohibited. Deals like these could pave the way for advertisers to work with publishers to establish a browser ID everyone can recognize and respect opt out for.

Shared Identity Solutions

What it is: A bunch of different providers and consortiums are pushing forward with new, standardized ways of identifying and storing user data without using third-party cookies. They are a third-party cookie-less option, but they rely very much on first-party cookies (audience data obtained directly from the publisher). Right now, there are many opportunists, including DigiTrust, ID5 and Ad Consortium, who have strong ID solutions. While currently, most were built to be compatible with third-party cookies (so the ID can be stored in a third-party cookie), they have been designed to work without them using first-party cookies.

Challenges: In theory, publishers that have log-in strategies can supplement these shared IDs with log-in data like email addresses, but the scale doesn’t yet match that of third-party cookies. Beyond that, however, these shared ID solutions require publishers to be willing to share their audience data with competitors, “In the last five years, there have been various consortiums of getting publishers to work together, said Nick Halstead, CEO of Infosum. “But commercial struggles will prevent getting publishers on board.”

As for the audience themselves, this also requires readers to log in, which is a tricky task in it of itself, as well as requiring consent. “One of the things that we need to really contemplate is how many people will actually log into any site and if they will stay logged in,” said Pete Spande, CRO of Insider. “If [shared ID solutions are] based on email and being logged in, will they participate and do the behavior that this plan is predicated on? A lot of evidence that this will not be the case.”

Ownership of the shared ID system is also a key point of contention. Google is working on a system that integrates a version of shared IDs (see Privacy Sandbox), however publishers and marketers both note that there could be issues with having a singular browser owning the platform that this data is stored in and whether or not other browsers will adopt that system as a result. “An independent non affiliated ID system sounds really good to me and that might create a universe where this party info might be traded on again,” said Scott Messer svp of media at Leaf Group.

You can read more about the challenges and mechanics of the shared identity solution here.

Google’s Privacy Sandbox

What it is: In place of third-party cookies, Google wants the industry to play in its Privacy Sandbox — a set of tools it launched last summer that will let advertisers run targeted ads without having direct access to users’ personal details. “There is one scenario where the world continues nearly unchanged,” said Messer. “That’s where Google’s solution comes out widely, everyone has their ID graphs going around and marketers simply leverage a different identifier and they keep spending as usual — as if not much happened at all.”

Using a trust API, it will ask a Chrome user to fill out an authenticity test, similar to CAPTCHA, once and then rely on anonymous “trust tokens” to prove in the future that this person is a human. Then each user is categorized into cohorts of similar interests (see federated learning), which are followed by machine learning to understand the group’s browsing habits. Google’s conversion measurement API alternative to cookies will let an advertiser know if a user saw its ad and then eventually bought the product or landed on the promoted page.

Challenges: The Sandbox is still in its infancy, so it is hard to describe exactly what it will look like once it’s in its adult form. Google has proposed many features, however, no actual platform or code exists for marketers to properly assess at this time. Some publishers and advertisers interviewed for this guide stated that they believe there is not a clear path forward for its launch at this time, which could potentially delay the timeline for when Chrome removes third-party cookies from its platform.

You can read more about what we know so far about Google’s Privacy Sandbox here.

Federated Learning

What it is: Google has been experimenting with the idea of using federated learning of cohorts (FLoC), which is a way for browsers to continue allowing interest-based advertising on the web. Rather than observing the browsing behavior of individuals, companies observe the behavior of a cohort of similar people. It relies on a robust model without sharing personally identifiable data.

At a high level, the system uses machine learning to train an algorithm across multiple decentralized devices without sharing or exchanging the data from those devices — that data remains stored locally, making it much more privacy-compliant. It differs from other centralized machine-learning systems where all data is uploaded to one server. These systems have been around for a while for non-ad related purposes.

Challenges: Google has been getting feedback from across the ad industry about how some of its proposals around developing a privacy-first ad-funded web. But critics are, again, wary of letting Google hold the keys to the artificial intelligence model that it created. Google’s FLoC has come under fire for potentially allowing bad actors to still access sensitive data. Each browser’s flock name identifies it as a type of web user, shared in the HTTP header, which is shared with everyone they interact with on the web.

Learn more about federated learning here.

Big winner: Google

Unsurprisingly, Google stands to profit the most from the death of the third-party cookie. In the absence of third-party cookies’ use with Chrome, a leading alternative at the moment for advertisers is to use Google’s first-party data within its own tools. This cements Google’s dominant position in digital advertising.

Winner: TV execs

TV executives are sitting pretty following the release of Google’s news. In the short term, ad budgets can safely be spent on TV, particularly as non-cookie-based ad targeting in streaming and connected television gets off the ground. That’s good news for commercial broadcasters such as ITV, which have been vocal in expressing to media buyers their plans to build a walled garden of their own.

Stands to benefit: Publishers

Publishers are in a better position to thrive with third-party cookies being absent because they possess their own information on their audiences. Whether or not they’ve done a good job of streamlining that information or created a database for those insights remains in the hands of the publishers themselves. The only issue that could stand in the way of them capitalizing on their first-party data is the walled garden effect, which limits standardization of data from publisher to publisher, making media buys less seamless for advertisers.

Needs to adjust: Advertisers

No longer having the third-party cookie to rely on, advertisers are forced to cozy up to publishers and rely more on their own customer information. Advertisers with reams of customer data can mesh that together with publisher data for targeted campaigns. The reach of advertising would decline and prices will likely rise as the supply-demand dynamic kicks in.

Learn more about the major players and the impact of the death of the third-party cookie here.