Secure your place at the Digiday Media Buying Summit in Nashville, March 2-4

The New Yorker switched up its daily newsletter, rolling out a voicier and more editorialized approach for readers’ inboxes. The idea is to infuse a bit more personality and original content — a newsletter strategy The New Yorker is now bringing to its daily product.

The Daily, which is free to read and publishes seven days a week, now begins with the biggest story of the day, followed by sections containing The New Yorker’s news and analysis, culture and essays, humor and cartoons and puzzles and games. At the end, a “postscript” links the news of the day or a moment in history with The New Yorker’s nearly century-old archive, according to an introductory post by Jessie Li and Ian Crouch, who are now co-authoring the flagship newsletter (Li has been responsible for that task for the past two years, while Crouch has been with The New Yorker for over a decade in a variety of roles).

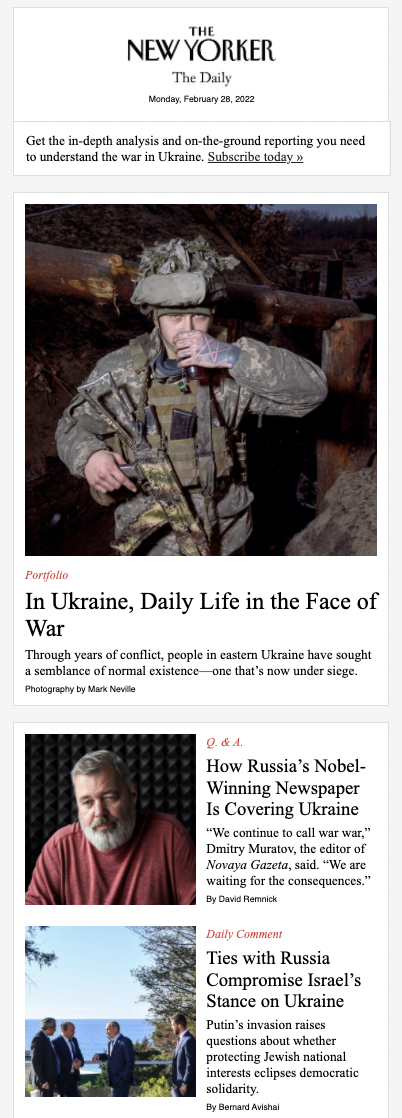

Here’s a look at the old version next to the new version:

Digiday spoke to Jessanne Collins, The New Yorker’s director of newsletters, to see what’s changed in the daily email and why the team decided to go beyond a straightforward curation of The New Yorker’s top stories, to give Li and Crouch the space to communicate to readers directly.

The New Yorker has 18 newsletters in total. This week, in conjunction with The Daily’s new look, the New Yorker also announced it would increase the publishing frequency of its crossword puzzle newsletter to five days a week.

The daily newsletter has nearly 2 million subscribers, according to a spokesperson, a 16% increase from a year ago. The newsletter has over 1 million daily opens. Newsletter visitors are twice as likely to subscribe to the New Yorker compared to site visitors overall, the spokesperson added.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Why did The New Yorker want to change up its daily newsletter?

We want to redesign it primarily because we just saw a lot of opportunity to make the newsletter more editorially robust and in line with everything The New Yorker is in its editorial and stylistic identity. Previously, it was a pretty straightforward collection of links that we had full editorial curational control over but we didn’t have the ability to include original material or packaging. We’ve introduced capabilities on the technical side to let us have a lot more elasticity in how we can package materials now. It always was edited and curated by a human but my sense was that you wouldn’t necessarily know that by looking at it. But the newsletter space, in general, is where personality, identity, the voice of the writer and the media entity can really come to life — so it felt like a missed opportunity for The New Yorker. We wanted to just bring that human element that was already there to the forefront rather than have it be behind the scenes.

How does the newsletter now differ from its previous iteration?

More or less every day at the top of the newsletter we are doing a little brief — a digestible bit of background on what the story of the day is. And that element in particular was a response to some of the user research that we did in a very early phase of this project one or two years ago where we heard from readers that they were having to look for ways to sort of parse through all of the material that’s coming at them, just in the media environment. There was quite an appetite for a pretty straightforward, digestible round-up of everything we had published. There were not too many people saying: “I want to read a 5,000 word email from the New Yorker.”

So the idea came that the newsletter could be a personalized and highly editorialized guide where our editors who are putting it together — you can trust them to be doing the work of reading all of the stories we are publishing and walking you through what you need to know and be reading.

What purpose does the reimagined daily newsletter serve?

One thing we wanted to do with this newsletter was to give readers sort of an on-road into understanding what the biggest story of the day for us was and why they need to spend the time reading it. In addition to kind of giving a background to the big story of the day, it packages up all of our other content in different, creative ways. It also gives us the flexibility to do of-the-moment little editorial parts — we call them “featurettes.” Our goal with this, in the context of the New Yorker, is that there [are] a lot of great newsletters that are of the long-form variety. But that’s not what we wanted to create with this particular product. The need we were responding to was our readers want a way to sort of have a quick and easy sort of digest to help them navigate the vast breadth and depth of everything that we do.

What’s some of the additional original content you want to appear in the newsletter?

We are in the early stages of experimenting with what we might do there but a good reliable example might be one of our newsletter editors could talk to a writer who is out reporting on a particular phase behind the story that the writer is writing. It could give some color about how the piece came together. It’s about creating spaces where writers themselves can come in and give their bit of backstory. It might be a little behind-the-scenes type of story where it’s a writer talking about their process or some aspect of their reporting of a big story. When we launched, we had some little tidbits of an interview with [staff writer] Michael Schulman, who was at the [Oscars] the night before — to give a sort of balcony row seat to the moment that everybody was talking about on Monday morning. We are creating places in the newsletter where we can showcase writers’ and editors’ voices and their thinking and their work behind the work.

Why is it valuable to infuse more ‘voice’ from Li and Crouch into the newsletter?

They literally read almost everything that we do, which maybe even your average editor doesn’t necessarily have the luxury of the time to do. They really have become experts on The New Yorker. We wanted to be able to let them harness that deep understanding of these stories that we are publishing and to let them follow their own curiosities. Part of my thought process was, how do we give them the space to take the newsletter reader on the journey that they themselves go on as they read [The New Yorker]? What sticks out to them? What would they suggest to a friend to read? We wanted to harness that energy and encourage them to run with that instinct to really use their own sensibility to what makes the story so special and highlight that for the reader.

How is The New Yorker measuring the success of its daily newsletter?

On one level: the newsletter space, the inbox, is a platform of its own and The New Yorker wants to have a version of itself that lives in that platform, just like we would have on other platforms. We know how powerful the newsletter and inbox is in terms of having that direct relationship to the reader, compared to other platforms that can be more unpredictable — that has been really important. On the business level: that direct relationship to the reader translates directly to a subscriber business model, which is what we are really focused on. At the core, we are looking to drive subscriptions and we have data that says that newsletter readers are much more likely to go on that journey to become subscribers. We want to stoke that relationship.

This article has been updated to reflect that Collins had meant to cite the Oscars, not the Emmys, when referring to an interview from The New Yorker staff writer Michael Schulman.

More in Media

From feeds to streets: How mega influencer Haley Baylee is diversifying beyond platform algorithms

Kalil is partnering with LinkNYC to take her social media content into the real world and the streets of NYC.

‘A brand trip’: How the creator economy showed up at this year’s Super Bowl

Super Bowl 2026 had more on-the-ground brand activations and creator participation than ever, showcasing how it’s become a massive IRL moment for the creator economy.

Media Briefing: Turning scraped content into paid assets — Amazon and Microsoft build AI marketplaces

Amazon plans an AI content marketplace to join Microsoft’s efforts and pay publishers — but it relies on AI com stop scraping for free.