Jessica Dunn has been on maternity leave from her job designing medical devices for the past two years. And her ability to take such an extended, unpaid sabbatical is due to the money she earns from posting images to Pinterest. Dunn, who boasts nearly 2 million Pinterest followers, posts images to Pinterest on behalf of brands and is compensated when those “pins” refer traffic back to those brands’ websites.

While the job requires approximately 40 hours per week of work, it allows Dunn the flexibility to work from home whenever she can find time away from child-rearing. She earns about $5,000 a month doing it, and it’s her sole source of income at the moment.

But that source of income has suddenly slowed to a trickle. Pinterest banned affiliate and redirect links from the platform two weeks ago, making it difficult for Dunn and other “pinfluencers” like her to earn money by pinning for brands.

“I was upset, because all the content I’ve created over the last year and a half, all those links have been blocked as spam,” Dunn told Digiday. “I’m lucky that I have a regular job to go back to.”

Dunn is one of the many so-called pinfluencers who make up HelloSociety, a startup that helps pair influential Pinterest users with brands and broker branded content campaigns between the two. And Dunn said that HelloSociety and its network of pinfluencers have been wrongly identified as affiliate marketers and “spammers,” when they are, in fact, some of the platform’s most dedicated users. Some of those users rely on Pinterest as their main, or only, source of income.

For Pinterest, alienating its most popular users is clearly not in its interest. At the same time, Pinterest is moving to build powerful monetization capabilities. Like other platforms, this can mean cutting off some on-the-side deals power users have and enacting rules on what kinds of work with brands is acceptable and which kinds need to go through Pinterest.

“This does not mean we no longer believe in popular Pinners,” Pinterest spokesman Mike Mayzel said in a statement. “They can continue to be paid to curate boards for brands’ profiles, consult and create original content for businesses.”

In the meantime, there is collateral damage. Pinterest’s recent ban on affiliate marketing, for instance, included a ban on redirect links, URLs that allowed HelloSociety pinners to track when their pins were clicked on. Redirect links allowed pinners to track how much traffic they were sending to brands’ websites. Brands, in turn, would compensate users by the amount of traffic they delivered.

But the ban on redirect links renders that compensation model non-existent. And HelloSociety’s users have already started feeling the pinch.

“Influencer incomes have already been impacted by the change — in some cases fairly significantly,” HelloSociety CEO Kyla Brennan said.

HelloSociety is still trying to work with brands in a “creative services” capacity, Brennan added, having its network create and curate pins for brands and not have them paid based on performance.

“Pinterest only wants pinners to be compensated when they curate a board on a brand’s account, which doesn’t provide the best value and, as a result, isn’t something most brands are willing to pay for,” Brennan said.

“This does not mean we no longer believe in popular Pinners,” Pinterest spokesmanMike Mayzel said in a statement. “They can continue to be paid to curate boards for brands’ profiles, consult and create original content for businesses.”

Influencers have recently become a popular marketing vehicle because they typically afford greater organic reach than a brand account, and their endorsements are typically seen as more “authentic” than ads, according to Tom Buontempo, president of social media agency Attention.

“If we can’t rely on having influencers work with our clients, then it obviously makes it much more difficult for our clients to leverage the platform in a way that we feel is more authentic than the ad product,” he said.

It should be noted Pinterest is in the midst of ramping up its monetization efforts. The platform is creating a new ad unit, working on a “buy” button that will allow users to purchase items directly from the platform and trying to work more closely with agencies to create Pinterest-focused brand campaigns.

Pinterest denied claims that the ban on affiliate and redirect links was related to its monetization efforts. Rather, it said that many affiliate links were spammy and hurting the user experience on Pinterest.

“It’s not spam. We’re not spamming people,” Dunn said. “We’re actually curating stuff that they love. They like, repin, comment and engage. And without our network of power users, they wouldn’t have all the content from brands.”

Approximately two-thirds of the pins on Pinterest are related to brands, according to Pinterest’s own figures.

Pinterest has previously stated that Pinterest will not replace existing affiliate and influencer networks with its own solution.

So pinners like Dunn and Katherine Accettura, a graphic designer from Carbondale, Illinois, who has more than 1 million Pinterest followers and makes a majority of her income by pinning on behalf of brands such as JC Penney, may soon need to find other jobs.

True to Pinterest’s spirit, Accettura was eternally hopeful about her future when she spoke to Digiday.

“I wish I could write Pinterest a letter and say, ‘Think of me,’” she said. “I’m still going to have a large amount of followers, and I’m just hoping to adapt any way I can.”

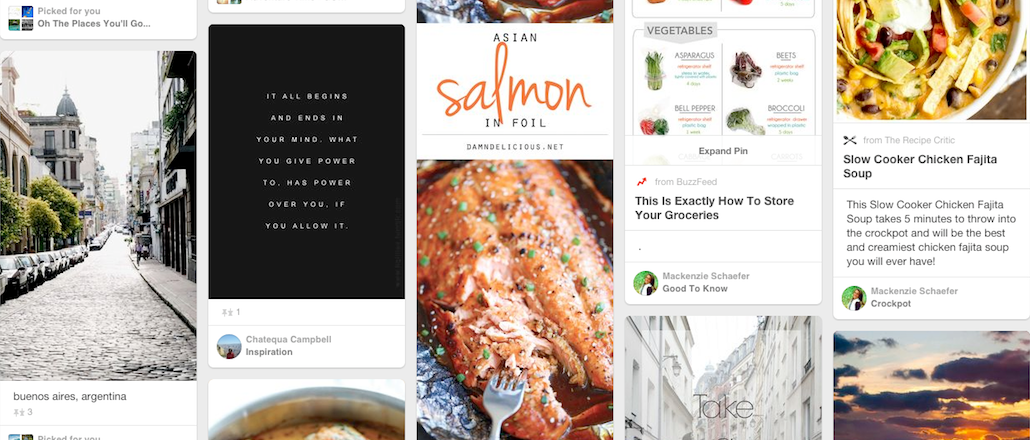

Image courtesy Pinterest

More in Media

In Graphic Detail: The scale of the challenge facing publishers, politicians eager to damage Google’s adland dominance

Last year was a blowout ad revenue year for Google, despite challenges from several quarters.

Why Walmart is basically a tech company now

The retail giant joined the Nasdaq exchange, also home to technology companies like Amazon, in December.

The Athletic invests in live blogs, video to insulate sports coverage from AI scraping

As the Super Bowl and Winter Olympics collide, The Athletic is leaning into live blogs and video to keeps fans locked in, and AI bots at bay.