Secure your place at the Digiday Media Buying Summit in Nashville, March 2-4

Inside the Atlantic’s triumphant and tumultuous run during the coronavirus pandemic

During a rambling press conference last month, U.S. president Donald Trump blasted the Atlantic as “a second-rate magazine,” “a failing magazine” and “a third-rate magazine that’s not going to be in business much longer.”

It was the kind of habitual press bashing typically bestowed on the larger, more frequent targets of Trump’s ravings — CNN, The New York Times, or the Washington Post. But the Atlantic had hit a nerve. Jeffrey Goldberg, the publication’s editor-in-chief, reported that Trump repeatedly denigrated American soldiers who died in war as “losers” and “suckers.”

The article, published on September 3, and Trump’s subsequent ire placed the country’s attention once again on the 163-year-old Atlantic, which is enjoying its most relevant cultural moment since the 19th century. “My formula is fairly simple,” Goldberg said. “We’re too small to do anything but the biggest things.”

The Trump scoop provided a boost not only to the Atlantic’s renewed sense of importance, but to its bottom line. Last month, the Atlantic accumulated about 60,000 new paid subscribers, the best month on record since it launched a paywall last September. Since then, the Atlantic has lured in about 370,000 new subscribers (and has about 650,000 total subscriptions).

Figuring in minor discounts, the new line of business likely brings the publication about $20 million in revenue a year. “It turns out that the thing we like to do — which is really carefully-done, sweeping, ambitious stories — is the thing that the market wants,” Goldberg said.

The subscription windfall comes thanks to a red-hot editorial streak in which the Atlantic has distinguished itself by helping readers stop and make sense of a disorientating news moment. Before many Americans took the coronavirus seriously, James Hamblin grabbed the internet’s attention with his February 24 story “You’re Likely to Get the Coronavirus,” and science writers Sarah Zhang and Ed Yong have authored definitive stories throughout the pandemic, sprawling and sobering reads like “How The Pandemic Defeated America.” The Atlantic’s traffic peaked in March with about 65 million unique visitors, according to Comscore.

The groundswell of recognition has set the Atlantic on the way toward a goal shared by many outlets: evolving from an advertising-backed business to one supported chiefly by reader revenue.

That happy tale, however, conceals a bleaker, more familiar undercurrent. In May, the Atlantic laid off 68 staffers (about 20% of employees) amid a pandemic advertising crunch and abrupt halt to the live events industry, once one of the company’s most dependable revenue streams — about 20% of its revenue pre pandemic. The publisher loses millions of dollars a year, in part because of the erosion of the ad business, but also due to aggressive spending on editorial and product following the 2017 acquisition of a majority stake by Emerson Collective, the organization led by billionaire investor Laurene Powell Jobs, the widow of Apple founder Steve Jobs.

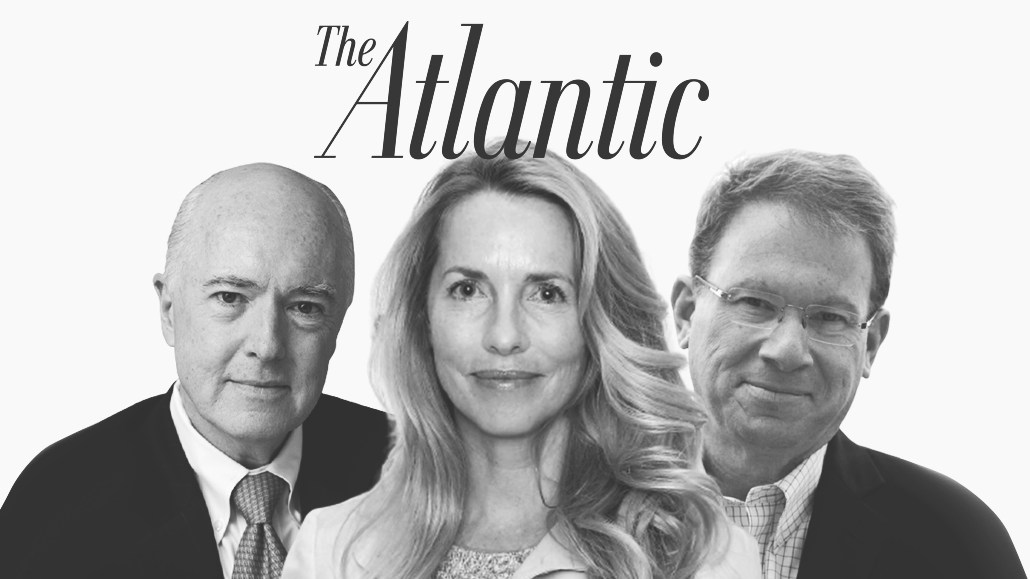

Meanwhile, a convoluted management structure makes it difficult to discern who is in charge of the path forward. David Bradley, the eccentric minority owner and longtime chairman, has been searching for a new CEO for a year after promising to transition out of management duties. He has bragged to those around him about interviewing more than 100 candidates, but the hunt continues for the person who will become the operational leader. In the meantime, Emerson shares oversight with Bradley and his band.

At the time of the sale in 2017, Bradley said Emerson would likely take over full control within five years, but last year indicated the arrangement might last longer. Bradley plans to remain on in a chairman emeritus role once the CEO is on board. “He has been put in charge of finding his successor for a job he doesn’t want to leave,” said one source with knowledge of the process.

The Atlantic has ambitious goals for the future: $50 million in consumer revenue by 2022. But whether that can push the publication back to profitability is far from clear. For now, The Atlantic’s financial future rests on Powell Jobs’ willingness to spend more of her fortune underwriting the publication. Two weeks ago, Emerson yanked its financial support for another of its media investments, the live events driven Pop-Up Magazine Productions, which shut down California Sunday Magazine. After years of fawning headlines like “Can Laurene Powell Jobs Save Storytelling?,” the philanthropist’s tolerance for losses clearly has its limits, even if that means showing media workers the door during a recession. Inside the Atlantic, staffers remain on edge.

“Emerson and Laurene aren’t investing in media to line their pockets with massive returns, but they do want media businesses, and a thriving media business is a self-sustaining media business,” said Michael Finnegan, the Atlantic’s president. “Not something they have to pour cash into year after year.”

From Emerson to Emerson

A decade ago, The Atlantic emerged as a surprising media success story. After purchasing the publication in 1999 for $10 million from media mogul Mort Zuckerman and suffering a series of money losing years, Bradley moved the magazine from Boston to Washington and hired James Bennet as editor and Justin Smith as its top executive. Their new formula became a roadmap for how to revitalize a print media operation: break down the wall between digital and print ad sales, cut costs, pump out more web traffic, and build a reliably money-generating events business. In 2010, the Atlantic began turning a modest annual profit.

With the company in the black, Bradley — who made his fortune through now publicly-traded consulting and research businesses — eventually told those around him that the next generation of his family had no interest in inheriting a publishing empire. He intended to cash out and, when scanning for potential billionaires, hit the jackpot with his first and only call: Powell Jobs, whose philanthropic and investment organization is named after one of the Atlantic’s founders, Ralph Waldo Emerson. In July 2017, the deal was announced. Emerson purchased 70% of the company for about $110 million, according to people familiar with the matter, and Bradley stayed on as chairman.

That was the Atlantic’s last profitable year. Almost immediately, Emerson infused the Atlantic with resources, growing staff by about 80 positions and bringing on well-known writers in the newsroom like George Packer, Anne Appelbaum and Jemele Hill.

According to those familiar with the Atlantic’s finances, the company made about $10 million in profit when Emerson invested. That soon flipped to a $20 million loss. While Emerson knowingly pushed the company into the red to make a meaningful expansion, growing the editorial, product, engineering and growth teams, the losses intensified as the wider advertising environment flagged. The Atlantic was used to digital ad growth of 30% year over year. But that began to slow and then move backwards in 2019, according to Finnegan.

Across the media landscape, a new model solidified — one based on diversified revenue streams in addition to advertising, like commerce and subscriptions. At The New York Times, the Washington Post, and the New Yorker, for instance — outlets that The Atlantic counts as peers — reader revenue, coupled with the journalistic sense of purpose from covering the frenetic Trump administration, drove a traditional “print” media renaissance (albeit not in actual print). The Atlantic’s leadership wanted to be a part of that movement, and they knew that the future of the business similarly hinged on turning digital readers into digital subscribers.

In September 2019, the long-discussed paywall arrived. Priced at $49.99 per year for digital access and $59.99 for print and digital (there is no monthly option), the Atlantic’s price tag is cheaper than competitors like the New Yorker, whose annual bundle and digital-only subscriptions are $149.99 and $99.99, respectively. Finnegan said that reader surveys drove the pricing, and that the company is now focused on getting legacy print subscribers to the new rates. But, “I think people could pay more, and we are certainly looking at price increases,” he said.

As the magazine quickly surpassed its original goal of 110,000 new subscribers over the first two years, competitors like Goldberg’s former boss at the New Yorker were noticing the impressive coverage. “The truth is, even though the New Yorker and The Atlantic are not the same in approach (why should we be?), it’s a good thing to see even your competitors being healthy and doing great journalism,” said New Yorker editor David Remnick. “Good for readers, good for the country.”

Of course, publishers big and small are mulling what the potential end of the “Trump bump” will mean for their businesses. Goldberg, for his part, doesn’t think that a post-Trump world will hurt The Atlantic’s momentum. “We’ve been explaining complex topics and the way American ideas work for 163 years,” he said. “I think we will continue to do that. The pandemic is not going away. The state of our culture is going to be fraught for a long time.”

In many ways, the Atlantic was well-positioned to rack up subscribers at this bizarre news moment. Writers at the magazine are allowed to write long, analytical stories. It has talented science, politics, culture, tech, and health teams. And the modern Atlantic has always been known for grand, talked-about pieces. Just not at this frequency.

Tony Haile, the founder of Scroll, said that he remembers Atlantic stories, such as Alex Tizon’s My Family’s Slave, frequently ranking among the top articles in terms of total engagement time when he led the measurement company Chartbeat. “The kind of the thing driving loyalty is the stuff The Atlantic has always been doing,” Haile said. “Those big crazy stories didn’t necessarily make that much money in the advertising years, but now act as a great anchor” when it comes to subscribers. And as that base grows, the company hasn’t abandoned its other lines of business. It launched Atlantic Brand Partners in an effort to strike larger, consulting-like deals with clients. Like many media companies, it has moved its events business online — with a much smaller team.

At the same time, the company remains in an interim leadership situation. Its last president, Bob Cohn, left in September of last year, with Finnegan taking on much of his duties. Privately, Goldberg, who has a chummy friendship with Powell Jobs, has groused about the crowded leadership structure, sources told me. (“We have great owners,” Goldberg said when asked about any frustrations).

People familiar with the matter say that Bradley has relished the opportunity to interview media executives for the position, so much so that they wonder whether he has slow-walked the process. Candidates for the position have included former Hollywood Reporter and Billboard chief Janice Min and Kevin Ryan, the founder of Gilt and Business Insider, though neither is still in the running. It’s unclear if there are any current candidates in talks.

Whoever takes over the company will do so in style — if workers are ever able to work in offices again, that is. Emerson purchased a new building in Manhattan’s Soho neighborhood prior to the pandemic, the company confirmed to Digiday. It will eventually be home to the firm’s offices as well as the magazine’s New York City presence — yet another splashy expansion.

A nervous newsroom

Goldberg said that the Atlantic has been punching above its editorial weight, taking on the Times and the Post with a far smaller staff, but it is still a sizable and expensive operation. Before the layoffs, the company had 150 editorial and 250 non-editorial employees. This spring, as the pandemic intensified, Atlantic staffers wondered if they would be the next media company to face furloughs or layoffs — or if they would be insulated thanks to their billionaire backer, who according to Forbes has a net worth of $19.6 billion. (Powell Jobs declined to be interviewed for this story).

When the layoffs did come down, the reductions were mostly targeted toward the parts of the business most immediately hit by the pandemic; on the business side, the events business and sales, and on the editorial side, the recruitment team, a handful of other staffers, and the video team (which, like at many media companies, had never really found a way to make money).

“We’re so proud of The Atlantic’s extraordinary journalism in 2020, from its coverage of Covid to its writing about race to its reporting on the Trump administration. We’re also thrilled by readers’ response, with record audiences and remarkable digital subscription growth,” said Peter Lattman, managing director of Media at Emerson and vice chair of the Atlantic. “It’s been a watershed year, and we’re confident the company is strongly positioned to excel in a post-pandemic world.”

Reporters and editors nevertheless took the cuts hard. “The layoffs were frustrating and blindsided the newsroom a little bit,” said one editorial staffer. “We thought we would have a clearer signal that cuts were going to be made.”

“I think management underestimated how painful it would be,” said another.

In recent weeks, however, employees say that morale has started to return to normal. Or as normal as it can be in this media environment.

“We talk to our colleagues and say that we all know the industry we’re in. Obviously, we’re living through unprecedented times,” said The Atlantic executive editor Adrienne LaFrance. “I do feel like we’re on solid footing, and it’s important for folks at The Atlantic to know that those decisions were made to keep us on solid footing.”

More in Media

From feeds to streets: How mega influencer Haley Baylee is diversifying beyond platform algorithms

Kalil is partnering with LinkNYC to take her social media content into the real world and the streets of NYC.

‘A brand trip’: How the creator economy showed up at this year’s Super Bowl

Super Bowl 2026 had more on-the-ground brand activations and creator participation than ever, showcasing how it’s become a massive IRL moment for the creator economy.

Media Briefing: Turning scraped content into paid assets — Amazon and Microsoft build AI marketplaces

Amazon plans an AI content marketplace to join Microsoft’s efforts and pay publishers — but it relies on AI com stop scraping for free.