‘A crisis boiling under the surface’: Agencies confront employee burnout

Within VaynerMedia’s New York Hudson Yards office is a quiet space meant to be a meditation room for agency employees to relax, filled with adult coloring books, a salt lamp and a chair.

For at least one agency staffer, it has become a safe space for panic attacks and crying sessions, known among her and some of her peers as the “cry closet.”

They happen when things get too tough at work. “Being at work exacerbated my problems because it made me face the fact that I felt very unfulfilled in my job because I felt that I was very bad at it.”

This staffer is not the only one. Agency staffers are reporting high levels of burnout and being worried about their mental health. For some, it’s linked to the very nature of the agency industry itself — hectic and relentless, dependent upon client whims and, these days, fraught with layoffs and other uncertainty.

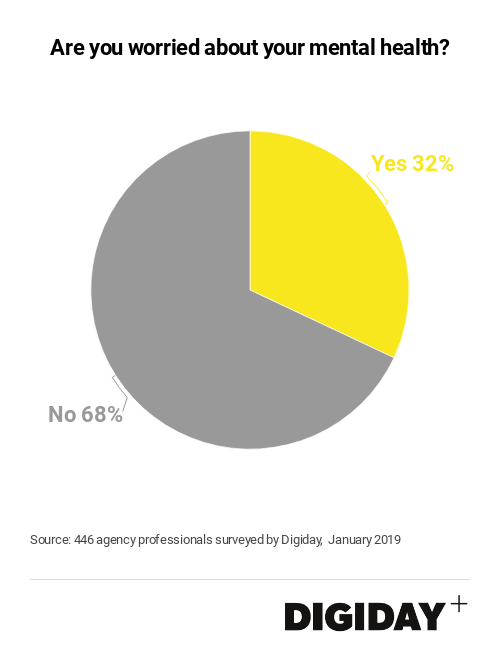

In research conducted by Digiday+, 32 percent of agency professionals reported being worried about their mental health, and it doesn’t matter what kind of agency, whether media or creative. This was across both media and creative agencies. This is about in line with national statistics: Mental Health America found that about 35 percent of employees in the U.S. have workplace stress that they say affects their lives. Burnout is a hot topic: A recent article examined how errand paralysis, stress and the idea that you should simply be working all the time have contributed to millennials as the burnout generation.

The Digiday survey, done of 446 agency professionals early in 2019, points to a correlation between mental health and the number of hours agency professionals are working a week. About 40 percent of people who work between 50 and 59 hours a week said they were worried about their mental health, compared to 27 percent of those surveyed who work between 40 and 49 hours a week who said they were worried.

Maddie Marney became a freelancer last year after eight years of working at media and creative agencies, often putting in 80-hour work weeks. Feeling burned out was a big reason.

“I could never make plans. You never knew if there was something during the day that would prevent me from going to a dinner or happy hour,” she said. “There were some days I would leave the office at 7:30 p.m., only to go home and log back on.”

Stephanie Nadi Olson, founder of Atlanta-based freelance organization We Are Rosie, now nine months old, said that around 900 members of the organization’s 1,100 freelancers left the agency world because they were overworked, underpaid or physically exhausted. Some people, she said, have left the country and are freelancing abroad, feeling like they couldn’t get out of that cycle without a dramatic, clean break.

“For people who are perfectionists or type A, or people who are just don’t want to be viewed as failures, it can create this psychological trauma,” she said. “They feel like, in order to be successful in this environment, I have to be unhealthy, emotionally worn out and exhausted. Not every agency is morally bankrupt, but a lot of them are.”

There is also a connection between salary and mental health — and, therefore, junior staffers are reporting higher levels of mental health problems. Of those surveyed, 41 percent of those making less than $50,000 a year said they were worried about their mental health, while only 28 percent of those who make $100,000 or more said they are worried about their mental health.

Ad agencies are people businesses. Big accounts mean more work; there are often tight and sometimes unreasonable deadlines. Margins are squeezed, and salaries, especially for those starting out, can be low. Turnover is high. At some agencies, that kind of cyclical burnout is built into the way things work: According to one vp at a social media agency, their agency will bring people on, work them 60 to 70 hours a week and then, when they leave for better opportunities, repeat the entire process over again.

‘Unspoken, urgent issue’

Dealing with burnout and mental health issues is still something not talked about freely at agencies. In a culture that is obsessed with creativity and driving success, it can be difficult to admit a problem.

Stephanie Redlener, founder of culture consultancy Lioness and managing director of talent strategy at consultancy DDG, works with ad agencies like Havas and companies like MetLife and IBM to develop their work culture and strategies to maintain talent. She calls the issue a “silent epidemic.” “It’s an unspoken, urgent issue,” she said. “People are ashamed to talk about it.” The issue, she said, hurts an industry already struggling to recruit and keep talent.

For people with predisposed mental illnesses, the industry’s harshness can make things worse. Aaron Harvey, owner at creative shop Ready Set Rocket, said his stressful work environment and long hours are exacerbated by obsessive-compulsive disorder, which he has struggled with since he was 10. In the mornings, he was pitching CEOs on creative campaigns, but by night, he would be drinking heavily, doing drugs and causing himself self-harm. One day, he found himself starring in the mirror as he held a butcher knife to his throat.

“It’s a crisis boiling under the surface,” said Harvey, who has, since his suicide attempt, has undergone treatment and has launched his own nonprofit Made of Millions to help people with mental illnesses. “When you put people in a pressure cooker, you’re going to have people boil over.”

Fixing the issue at agencies is not easy. Governing bodies like the 4A’s host training workshops for managers, distribute materials that talk up wellness and offer accreditation to those doing a good job. But there’s only so much they can do. Agencies have added things like nap rooms. Some agency professionals say governing bodies should mandate hours worked or a way to compensate overtime hours despite salaries. “Mandating hours is really difficult especially in our industry because it is driven by clients,” said Simon Fenwick, 4A’s evp of talent, engagement and inclusion.

One thing is for sure: Meditation rooms and ping-pong tables are not going to cut it anymore

More in Marketing

Star power, AI jabs and Free Bird: Digiday’s guide to what was in and out at the Super Bowl

This year’s Big Game saw established brands lean heavily on star power, patriotic iconography and the occasional needle drop.

In Q1, marketers pivot to spending backed by AI and measurement

Q1 budget shifts reflect marketers’ growing focus on data, AI, measurement and where branding actually pays off.

GLP-1 draws pharma advertisers to double down on the Super Bowl

Could this be the last year Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, Hims & Hers, Novartis, Ro, and Lilly all run spots during the Big Game?