Secure your place at the Digiday Publishing Summit in Vail, March 23-25

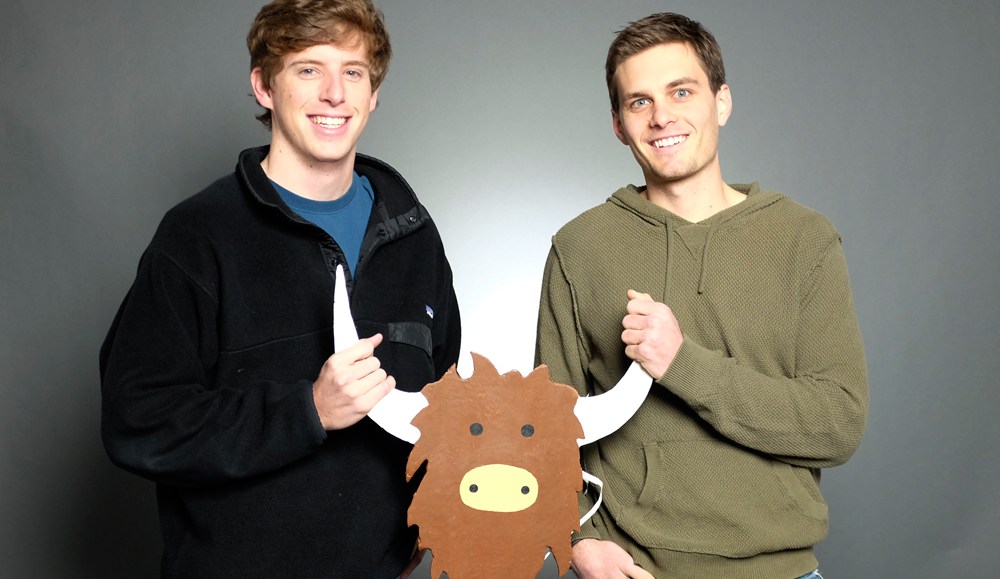

Brooks Buffington is well aware that his improbable name could just as easily belong to a professional wrestler, adult film star or scion from the northeastern U.S. And while he fits none of those descriptions, he does square with the “brogrammer” archetype. Buffington and his former Furman University fraternity brother Tyler Droll are the co-founders — and COO and CEO, respectively — of Yik Yak, the social media app that has swept across college campuses across the country.

Since Buffington and Droll unveiled it last November, Yik Yak has gone from a viral sensation at their alma mater to being used at 1,000 schools nationwide.

The app has attracted more than just coeds, too. Two weeks ago, Sequoia Capital invested $62 million in Yik Yak, reportedly valuing the anonymity-based social app at more than $300 million. The venture capital firm has an impressive track record to date: Its portfolio includes social media successes Instagram (sold in April 2012 to Facebook for $1 billion), Tumblr (sold in May 2013 to Yahoo for $1 billion) and WhatsApp (also bought by Facebook for a whopping $19 billion).

And Yik Yak accomplished all this despite the young founders’ relative lack of interest in social media. Neither uses Instagram or Twitter much, and they resisted the Snapchat craze that took over Furman their senior year, Buffington said. Facebook was “huge” for them in high school, but it had had lost much of luster by the time they graduated college. But it was their dissatisfaction with other social platforms — ones they found to be too public — that allowed them to identify and ultimately exploit an underserved niche.

“For creating a huge social media app, Tyler and I probably aren’t the biggest social media users,” Buffington told Digiday. “But we definitely took a lot of cues from the platforms we saw problems with.”

What they wanted was an app that would allow college students to post publicly but anonymously. Now, Yik Yak has millions of users, tens of millions of dollars in VC, hundreds of millions dollar in theoretical value, interest from Facebook and trepidation from advertisers that will eventually constitute Yik Yak’s revenue source.

A “local, anonymous Twitter”

Buffington and Droll met while pledging the same fraternity at Furman University, a small — 2,798 enrollees, according to U.S. News and World Report — liberal arts school in Greenville, South Carolina, with a notoriously homogenous student body. The Princeton Review ranked it the No. 1 college for “Little Race/Class Interaction.”

“We both shared a passion for apps and technology, and wanted to make something that would be huge and world-changing,” Buffington told Digiday.

Their first attempt, Dicho, an app that would allow users to simultaneously poll multiple friends, flopped. But the two recent college grads decided to try again, this time drawing inspiration from Twitter.

Droll was intrigued by anonymous Twitter accounts that had become wildly popular on campus, and he saw an opportunity in their success. His vision was to create create a “local, anonymous Twitter,” and that’s what Yik Yak became.

“I thought, there have to be more than five funny people on campus,” Droll said. “When the quietest kid sitting in the back of the class can share something and it can get to the top of a feed, it really levels the playing field.”

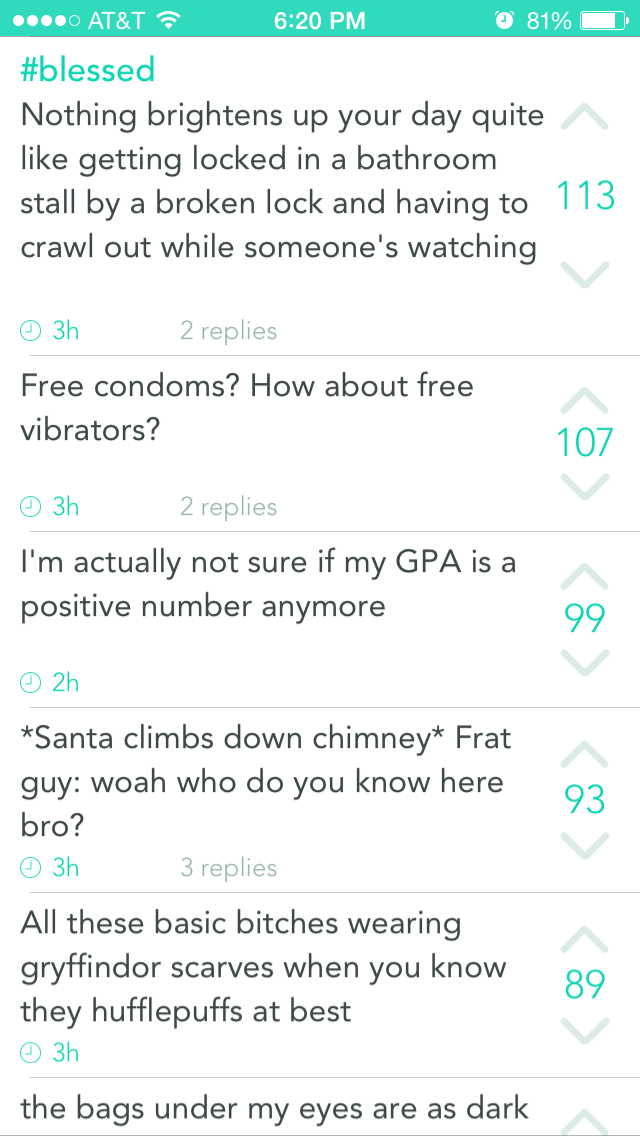

Unlike other social platforms based on following or connecting with certain profiles, Yik Yak would be entirely anonymous. There would be no profiles, and messages would be public and based upon location. When users opened Yik Yak, they would see a feed of anonymous posts contributed by other users in the area, turning into a digital bulletin board.

Integral to the service was an up- and downvote feature similar to that of reddit. The more upvotes a “yak,” or Yik Yak message, received, the more prominently it was featured in users’ feeds. Upvotes also increased a user’s “Yakarma,” a rating system that was tied to users’ devices, allowing them to gauge their popularity on the platform.

Buffington and Droll marketed the app launch by emailing student clubs, fraternities and sororities at Furman and other nearby colleges. From Furman, it spread to Georgia Tech University, then to University of Georgia.

The turning point was spring break in 2014. The number of schools at which Yik Yak was being used went from more than 30 to more than 300 in the weeks following that collegiate rite of passage. Now Yik Yak is active at “close to 1,000 schools,” Droll said.

“You’d be hard-pressed to name a major institution we don’t have a big presence at,” he said.

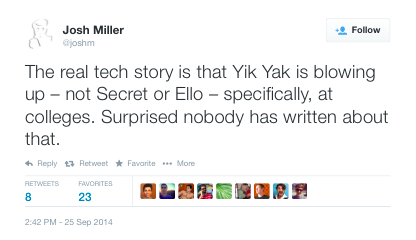

The app has become so popular on campuses, in fact, that Facebook — the reigning social media king that itself started as a college-based sensation — has taken notice.

Facebook product manager Josh Miller referenced Yik Yak “blowing up” at colleges in a September tweet he has since deleted. Miller and Facebook soon thereafter debuted Rooms, a Facebook-owned app.

That size isn’t reflected in comScore data, however, which put Yik Yak’s number of unique U.S. user at 1.8 million as of October. Yik Yak would not disclose how many users it has.

Tapping into identity fatigue

The co-founders attribute the app’s success to what some have called “identity fatigue,” Internet users’ growing weariness with having their digital communications attached to their real-world personas and thus susceptible to public scrutiny.

“Once you have a profile, you’re expected to act a certain way. People only post the best, most beautiful parts of their life on Instagram,” Buffington said. “On Yik Yak, you just put something out there, and if it doesn’t resonate with anyone, it’s not a reflection on you.”

And unlike every other social media platform, established or nascent, Yik Yak has shown a disregard for multimedia. Yaks only accommodate text.

But Yik Yak’s strength with users could ultimately prove its weakness as a business. Perusing the Yik Yak feed for this reporter’s alma mater yielded numerous hilarious posts and typical college chatter about pulling all-nighters and eating ramen. But it’s conversations about other college pastimes — drugs, casual sex, binge drinking, general pettiness — that might give advertisers pause, according to Ian Schafer, CEO of digital agency Deep Focus.

Droll said the platform will be looking to integrate local advertising in a few years. Like its Sequoia Capital brethren, Yik Yak wants to get 100 million members before it starts thinking seriously about advertising, and he doesn’t consider Facebook to be the app’s most immediate competition.

“This is the new Twitter,” Droll said. “A live pulse. A real-time feed of what’s going on.”

More in Media

Media Briefing: As AI search grows, a cottage industry of GEO vendors is booming

A wave of new GEO vendors promises improving visibility in AI-generated search, though some question how effective the services really are.

‘Not a big part of the work’: Meta’s LLM bet has yet to touch its core ads business

Meta knows LLMs could transform its ads business. Getting there is another matter.

How creator talent agencies are evolving into multi-platform operators

The legacy agency model is being re-built from the ground up to better serve the maturing creator economy – here’s what that looks like.