Last chance to save on Digiday Publishing Summit passes is February 9

Last June, Vanity Fair launched The Hive, its first vertical outside the storied magazine, with a roster of star writers and social-first strategy. But to Mike Hogan, the magazine’s digital director, the brand was significant in another, less obvious way.

“To launch it all internally and have it happen on time and without major glitches is a new experience for us,” he said.

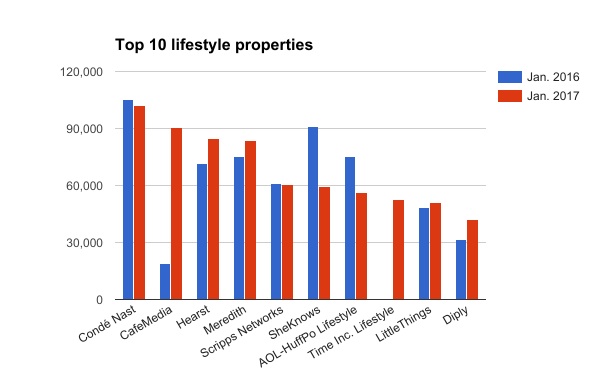

If Condé Nast’s glossy magazines are first-class, its digital operation for years has been a distant second. With its strength in print ads, digital wasn’t a priority. Forget about being ahead of the curve: It took years just to get magazines their own websites; Vogue.com didn’t launch in earnest until 2010. For the most part, Condé titles treated their sites as promotional vehicles for driving print subscriptions. It continued this approach even as other magazine companies like Hearst and Time Inc. were beefing up their digital capabilities and talking ambitiously about going toe-to-toe with digital natives like BuzzFeed and Vox Media.

The lack of investment made it hard to keep what digital talent the company had and to attract digital ad dollars. John Wagner, group director of published media at PHD, said that Condé Nast saw its competition as other legacy print publishers, and it led with print even when the advertiser was asking for digital.

The company has quietly been catching up, though. In 2014 it named its first chief digital officer, Fred Santarpia. In the two years since, Condé Nast’s digital audience grew 76 percent while time spent on the sites has increased 132 percent, per the company. “It’s a great start,” he said.

‘Pop-up on top of pop-up’

Collaboration is a matter of survival for modern publishers. Digital is a scale game, and the silos that worked fine for print magazines would hold them back online. The company’s brands were losing ground to faster-growing, nimbler digital pure-plays like BuzzFeed. At a point, there were as many as 15 content management systems in use, which made it hard to distribute large volumes of editorial content to partners like Facebook or Yahoo and sell advertising across titles. Employees who moved from one brand to another often had to be retrained in the new system.

“We were incredibly hard to work with,” said Santarpia, who had come from the same position at Condé Nast Entertainment, the company’s video arm. “Not only were our sites incredibly slow, but you’d get pop-up on top of pop-up on top of pop-up.” The digital staff was “complacent” and lacking in mobile skills. “I didn’t have experienced designers. I didn’t have data scientists.”

Other legacy publishers Time Inc. and Hearst have modernized by pooling editorial resources and pushing titles to share stories. But forcing that kind of collaboration would be tricky at Condé Nast, whose famous print titles including Vogue, The New Yorker and Wired had long run as staunchly independent businesses. The challenge for Santarpia was to balance the need for efficiency without cramping the brands’ individuality.

Balancing scale with independence

Santarpia decided that there should be certain principles every site would have to adhere to — there would be no more annoying pop-up ads, for example, and sites had to load fast, a requirement that he said led to “many fights with editors on a new product because it didn’t meet a site speed.”

He centralized functions like audience development, research and social media but dedicated experts in those areas to the individual brands. All 21 brands would be migrated to a homegrown content management system called Copilot, which would help sites publish and innovate faster. All in all, he’s turned over 65 percent of the digital staff.

Being on a common platform made it easier for brands to syndicate their articles outside the company. There were more platforms than ever demanding publishers’ content, and while it was up to each brand to decide their distributed strategy, they would all use the same Copilot interface to plug into Apple News, Facebook Instant Articles and Google’s Accelerated Mobile Pages. It’s also made it easier for brands to share tools and features. A tool Vanity Fair created that lets it A/B test personalized article recommendations is now used company-wide.

“We wanted the individual brand strategy to choose what they’re going to focus on,” Santarpia said. “It’s very easy to get to templatizing everything. That’s not who we are. We very much value the individuality of brand voices.” At the same time, he said, “scale and quality are not mutually exclusive goals.”

Cooperation is still largely left up to the brands themselves. There’s no mandate that brands publish stories from sister brands, but if they want to, Copilot is supposed to make that easier, too.

Vanity Fair’s Hogan said there was concern about how the transition to Copilot would go, but Santarpia played the part of football coach, saying, in effect, “I’m not going to mess with your content vision, I’m going to provide the support necessary to have success in digital.’ That was the right answer.”

Beyond cutting load time and growing traffic, Copilot’s benefits have differed from site to site. For GQ, Copilot made it easy to test different content recirculation modules, said Mike Hofman, GQ’s executive digital director. Changes like that have helped increase time spent on GQ.com 117 percent year over year.

“The best CMSs make everyday tasks easy and out-of-the-ordinary ones possible,” Hofman said. “What you see is a lot of brands experimenting and sharing their learnings and the actual features themselves.”

Going for engagement, not clicks

The timing for these strides is good, as advertisers growing increasingly aware of the problems that a scale-obsessed digital media model has wrought and are becoming more interested in how sites are engaging with audiences instead of just their sheer volume of clicks. Condé Nast’s digital revenue increased 22 percent in 2016 and now accounts for 30 percent of total revenue, according to the company.

Buyers said the company has done a lot to improve its digital sales talent, their pitch and the products themselves. Greg Smith, head of investment at MEC, said the company is still too print-centric and expensive and their ideas often feel prepackaged, but that it’s done a good job of wrangling the brands so agencies can buy ads on multiple brands at once. “Their pride, sense of entitlement can be off-putting, but at least they’re not seeing themselves as a commodity,” he said.

PHD’s Wagner said the publisher has done well to use its first-party data to match ad campaigns to their target audiences, position itself against digital-only competitors and increase its traffic without sacrificing editorial quality.

“They’re definitely staying pure to who they are as a company,” Wagner said. “They’re not going down that, ‘let’s get the click.’”

Condé Nast needs to do more to show younger planners and buyers that it should be thought of the same as digital-only publishers, though, Wagner said. “Having a seat at the table is more important for them when their pure-play competition is champing at the bit to come in every day.”

Going forward, the massive audience gains of the past couple of years are expected to taper off, and the challenges will be for the company to find growth through personalization and new product launches like The Hive. Later this year, the company will also face another big task as it migrates its international editions to Copilot, one Santarpia doesn’t take lightly.

“It is exponentially harder because you have each country doing their own thing and within each country, each brand doing its own thing,” he said. “It’s a couple years behind, but the good news is, they’ll benefit from the things we’ve learned.”

More in Media

In Graphic Detail: The scale of the challenge facing publishers, politicians eager to damage Google’s adland dominance

Last year was a blowout ad revenue year for Google, despite challenges from several quarters.

Why Walmart is basically a tech company now

The retail giant joined the Nasdaq exchange, also home to technology companies like Amazon, in December.

The Athletic invests in live blogs, video to insulate sports coverage from AI scraping

As the Super Bowl and Winter Olympics collide, The Athletic is leaning into live blogs and video to keeps fans locked in, and AI bots at bay.