Secure your place at the Digiday Publishing Summit in Vail, March 23-25

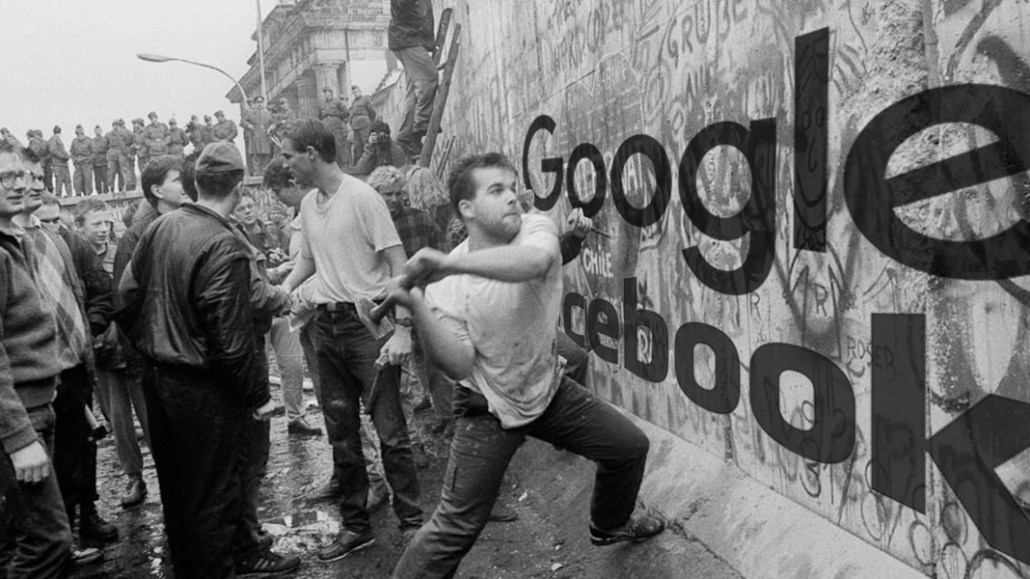

Media companies are speaking up against the dominance of Facebook and Google

This article is a free preview of the new issue of Digiday magazine, our quarterly print publication that’s distributed to Digiday+ members. To find out more about Digiday+ — and to subscribe — please visit the Digiday+ section.

It was April 2016, and BuzzFeed had just exploded a watermelon on Facebook Live, making it Facebook’s most-watched live video to date. BuzzFeed was flush with $3.1 million in Facebook money, making it the media company the platform paid the most to make live video content, ahead of even The New York Times and CNN. Just a few days later, onstage at Facebook’s F8 developer conference, BuzzFeed founder Jonah Peretti expounded on all the live video the viral content company could make for Facebook, including even a game show. Facebook and BuzzFeed seemed to be arm in arm, marching into the brave new world of live video.

That was then. These days, Peretti’s spiel has turned into a rant at conferences, to media outlets and to BuzzFeed staff that Facebook needs to share more of its news feed revenue with publishers. It’s a bold statement for a media company that literally built its business around Facebook. It signaled more broadly to the rest of the media landscape that the platform-publisher imbalance wasn’t just hurting traditional media.

“It’s in Facebook’s interest to share news feed revenue, not because it’s good for the world, but it allows Facebook to have some control over what’s showing up in the news feed,” Peretti later said in an interview with Digiday. “It would drive a lot of benefits for their business and help some media companies have better models.”

It used to be that criticizing the mighty platforms was something media executives would only do behind closed doors, in hushed tones. The fear, as Wired Editor-in-Chief Nick Thompson recently referenced on the Digiday Podcast, is Facebook has a dial somewhere that can be turned to cut off media that gets too uppity.

But now, publishers are at the end of their ropes, and even formerly ardent Facebook boosters like Peretti are finding their voices. The biggest target is Facebook, due to its audience reach, influence and frequently changing strategy that publishers have scrambled to keep up with. The feeling at many publishers is they got a raw deal. They helped Facebook by feeding it content to keep people engaged, and Facebook has meanwhile taken a huge chunk of their business through a better ad system.

Peretti is joined by other publisher critics, chiefly News Corp chief Rupert Murdoch and his top newspaper executive, Robert Thomson, who in blunt and sometimes florid terms charge that the tech giants are damaging journalism’s business model and should do more to compensate media companies. According to Wired, Murdoch has gone further, bluntly threatening Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg last year that they would attack Facebook unless the platform did a better job of compensating publishers. Since then, Thomson has laid out terms: “carriage fees” that Facebook would pay publishers. Facebook hasn’t dismissed the idea, either; Campbell Brown, news partnerships chief at Facebook, responded “never say never” when asked about it at the Code Media conference in February.

Justin Smith, CEO of Bloomberg Media, has been using his perch to warn other publishers about the danger of rushing head-first into giving their content to distribution platforms. Linda Yaccarino, ad sales boss for NBCUniversal, has become an evangelist for fixing digital advertising, which has included bashing Facebook for failing to meet the measurement standards that television is held to. “It was after years and years of the inability of the industry to keep up with consumer behavior, which was frustrating all of us to a boiling point,” she says.

Media executives are still lobbying the platforms behind closed doors. But by speaking publicly, they hope to sway advertisers that are spending more and more of their budgets with the platforms. They also are holding out the possibility that Facebook truly fears: a united front to impose stringent regulations on it either in the U.S. or Europe. Media wields outside influence when it comes to swaying public opinion. And the leverage media has — something Murdoch is well aware of — is denting Facebook’s public image and standing with government officials and regulators.

Indeed, after years of going from strength to strength, Facebook had a rough 2017. Sure, profits continued to soar, but the aftermath of the U.S. presidential election and questions about what role Facebook played dogged the company. On a parallel track, the media has been falling out of love with Facebook for years.

Starting in 2015, Facebook introduced Instant Articles and paid publishers to make live and news feed video for the platform, giving publishers hope that they could build a real business on the platform. But the revenue hopes never really panned out, and Facebook kept changing tack on video, which was exasperating for publishers that organized themselves to give the platform what they thought it wanted. Whole companies got venture capital funding on the basis of those hopes. All the while, Facebook was sending less organic traffic to publishers.

Around that time, Jason Kint, CEO of digital publisher trade association Digital Content Next, crunched the numbers and found that all the growth in digital advertising was going to Google and Facebook, which became his cause célèbre.

“You’re always looking for simple ways to describe to the market that it’s not right,” Kint says. “It’s pretty hard to argue most of the growth going to two companies is healthy.”

At the same time, public opinion started turning against Google and Facebook after the discovery of “fake news” leading up to and during the 2016 election, which gave media companies leverage. There’s growing awareness about the addictive nature of technology. In 2017, the News Media Alliance, a trade group representing 2,000 newspaper companies from the Times to McClatchy, began to seek an antitrust exemption from Congress so its members could negotiate collectively with the platforms. Along with the exemption, David Chavern, CEO of the News Media Alliance, has been lobbying the duopoly to provide subscription, brand, data and revenue support to publishers.

“You’re trying to highlight the problem for Google and Facebook, you’re trying to make policymakers aware of this problem, you’re talking to the broader public about the fact that this is not a legacy versus digital problem,” Chavern says.

In some ways, U.S. media execs are catching up to some of their counterparts in Europe, where suspicion of and opposition to U.S.-born tech giants runs deep, there are influential media companies like Axel Springer and there’s a long history of sensitivity to privacy concerns. The U.S. media hasn’t overtly asked for the platforms to be broken up or regulated, which seems like an unlikely outcome. But if publishers are entering the acceptance stage of their loss of faith in platforms, they’re getting more vocal.

The tech companies are at least listening, and then some. Facebook, along with Google, is testing subscription support for publishers. Google has expanded its fast-loading mobile pages to accommodate more article formats and introduced an ad-blocking version of Chrome that quality publishers hope will lead to higher ad demand for their own sites. Chavern is hopeful there will be progress on his antitrust initiative this year. There’s extra urgency now with research highlighting the decline in society’s trust in social platforms and the potential rub-off effect of that on publishers, along with consumer brands, when they appear on those platforms.

In the U.S., though, the number of people speaking out is still limited to just a handful. The vast majority of publishers use Google for their ad stack; Google and Facebook still contribute some 70 percent of publishers’ referral traffic. There’s still a pervasive fear that in speaking out too loudly or too often, someone at Facebook will turn a dial and turn off their referral traffic entirely.

“There’s no upside to being in the public on this,” Kint says. “They can’t survive without them.”

More in Media

How medical creator Nick Norwitz grew his Substack paid subscribers from 900 to 5,200 within 8 months

Creator Playbook: Unpacking the strategy behind medical YouTuber Nick Norwitz turning to Substack to significantly grow his brand.

Media Briefing: In the AI era, subscribers are the real prize — and the Telegraph proves it

In an era where AI is eroding referral traffic and third-party distribution, a subscriber who pays directly has become the most valuable reader a publisher can own. Springer just bought over a million of them.

Layoffs hit LADbible Group’s social video team amid slower user-generated content growth

Social-first publisher LADbible is in the middle of a second round of layoffs to its social video team, having suffered massive drop-off in Facebook video engagement.