Last chance to save on Digiday Publishing Summit passes is February 9

The Guardian was always the trust-fund kid of newspaper publishers: While others had to cut to the bone, The Guardian could rely on an endowment to not worry about bleeding money. The time has come for The Guardian to make it on its own.

Last week, the paper laid out a three-year plan to cut 20 percent of its losses this year, about £54 million ($77 million), and lay the groundwork for growth by 2018. As part of the changes outlined in its memo, Guardian editor-in-chief Katharine Viner and chief executive David Pemsel propose a re-vamped membership scheme, centralized data teams and a new ad model focusing on video and branded content.

Here’s how the Guardian can drive a profit.

Scale solves a lot of problems.

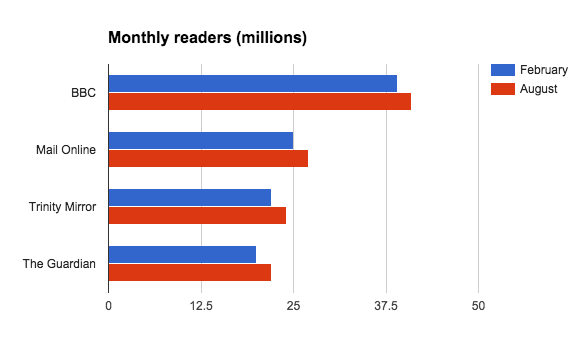

Unlike other newspapers, The Guardian has embraced an “open” model that means its content must remain freely accessible. The problem: Such a model can only work at much larger scale. Right now, The Guardian attracts just 22 million unique visitors a month and has hovered around this mark since early 2015, according to comScore, which simply isn’t enough to operate a 500-plus newsroom.

Viner and Pemsel said they are continuing to focus driving scale internationally in Australia and the U.S. The paper launched in the States in 2011 and currently ranks sixth in comScore’s newspapers category, reaching 12 percent of the desktop and mobile population. In Australia, it ranks fourth and reaches 10 percent of the desktop population. “Neither of these countries has a queue of left-leaning competitor news organizations,” points out Douglas McCabe, CEO at Enders, giving the Guardian room to dial up its scale in these territories.

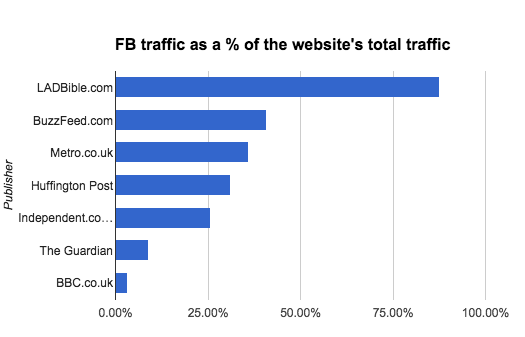

Social is another potential scale driver that The Guardian hasn’t fully cracked yet. According to Internet analytics firm SimilarWeb, when comparing the first half of 2015 with the second, Facebook desktop referral traffic to Guardian properties fell from 11 percent of all traffic to 9 percent.

Double down on membership.

But scale is only part of the battle, and, McCabe points out, doubling your audience doesn’t automatically mean doubling your revenue. The Guardian has conceded that it cannot drive profits purely through an online advertising model and has come back with a more formulated membership strategy.

Reluctant to offset losses by implementing a paywall, The Guardian launched its membership scheme in 2014. Prices range from £5 to £60 a month ($7 to $86), with different tiers offering a combination of tickets to masterclasses, events and contact with journalists.

In an email, a Guardian rep said it does plan to double reader revenue, though, and so plans to produce “journalism which only our members can access,” but a full-scale paywall seems unlikely.

It’s a note on semantics too, said McCabe — people will respond to a paid-for membership in a more respectful way than if it introduces a blanket paywall.

It’s perhaps this soft approach that has contributed to The Guardian’s losses, according to James Harris, global chief digital officer at Carat. “Their idealistic view of the world is part of the problem,” he said. “It’s the Jeremy Corbyn of the media word — it wants to give everything away for free, but it doesn’t make good business sense to do so.”

Inject more insight into branded content.

The Guardian won kudos for being among the first U.K. news organizations to open up an in-house content agency, Labs, in early 2014. Now a 450-strong team, it has been criticized for having burned through too much money too quickly. But digital revenues were up by 20 percent last financial year to £81 million ($115 million) with the bulk of this coming from display ads. Far from being a get-rich-quick scheme, content partnerships with brands is a long-term gain to build more trust with readers and more direct relationships with advertisers.

With more competition from branded content units from Telegraph, News UK, the New York Times and others, there are a couple of things the Guardian could do to keep it competitive, said Daniel Wood, head of media partnerships at Mediacom.

“Commercial content shouldn’t be the poor cousin of editorial,” he told Digiday. The Telegraph’s content house, Spark, is mindful of giving similar weight to commercial and editorial content. It can confidently do this because it has robust reader data and insight behind it, according to Wood. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this leads to better performing pieces of content for Mediacom’s clients, although he couldn’t disclose who.

The Guardian is still in the early stages of opening up its data to advertisers, and it is far from being universally implemented, according to Wood.

Centralize data teams to drive subscriptions.

The Guardian is focusing on bringing together the audience-insight and customer-data teams together, centralizing them in order to drive more relevance in advertising and in editorial, and so turn readers into paying subscribers.

“The FT’s analysts track not just ad performance (it grew subscriptions by 110 percent last year through a targeted ad campaign) but the content journey of the reader, continually optimizing, downgrading and upgrading content on the homepage so to encourage more subscriptions,” said McCabe. “It can make a significant difference.”

More in Media

Brands invest in creators for reach as celebs fill the Big Game spots

The Super Bowl is no longer just about day-of posts or prime-time commercials, but the expanding creator ecosystem surrounding it.

WTF is the IAB’s AI Accountability for Publishers Act (and what happens next)?

The IAB introduced a draft bill to make AI companies pay for scraping publishers’ content. Here’s how it’ll differ from copyright law, and what comes next.

Media Briefing: A solid Q4 gives publishers breathing room as they build revenue beyond search

Q4 gave publishers a win — but as ad dollars return, AI-driven discovery shifts mean growth in 2026 will hinge on relevance, not reach.