Secure your place at the Digiday Publishing Summit in Vail, March 23-25

It has been an interesting start to the new year. Donald Trump is president, and fake news is a widely discussed phenomenon.

Although the exact definition of “fake news” has been severely distorted as people (including Trump himself) have hurled the term as an insult toward anyone they simply disagree with, data show that it remains a popular topic internationally. Since the presidential election, coverage of fake news has increased as reporters tried to explain why people who primarily got their news through social platforms couldn’t tell when they were sharing false stories, and how automated ad buying enabled the fake-news ecosystem.

“As reporters uncovered the sources of many of the fake-news stories, the global nature of programmatic selling and buying was revealed,” said Forrester analyst Susan Bidel.

Media coverage

For a few months the press has extensively covered fake news. Brandwatch found that since the beginning of October, there have been about 54,000 stories with “fake news” in the headline. As the chart below shows, the stories began coming out in waves after the election.

A MediaMath spokesperson said that awareness of fake news increased around the election because fake news was pushed out to confuse voters and influence the outcome of the election, when previously fake news had been relegated to fringe websites and distributed in lower quantity.

International coverage

The press coverage of fake news has extended beyond U.S. borders. Brandwatch data track only activity in English. But outside the U.S., there were about 10,000 stories with “fake news” in the headline since October. The U.K. had the most stories, with about 2,000.

“This is a global issue,” Bidel said. “Fake news will be a problem wherever fake-news generators can make money.”

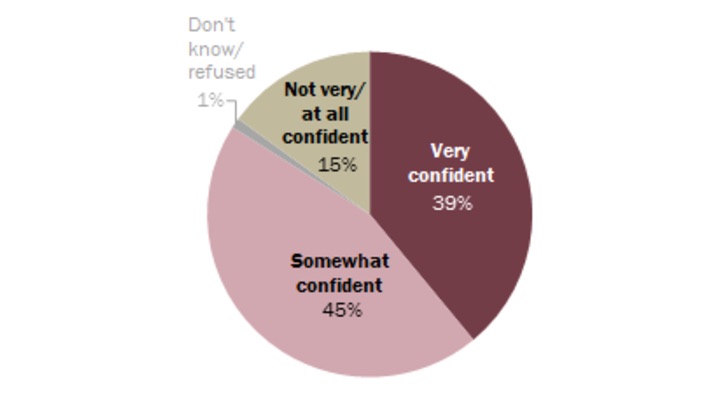

User confidence

Despite all the reports of people being fooled by false stories, a recent Pew report showed the majority of respondents were confident in their ability to detect fake news. But that confidence is often misplaced.

Social platforms

There is plenty of blame to go around when it comes to misleading content. But the role of social media in facilitating the spread of misinformation cannot be overlooked. As BuzzFeed reported, bogus stories were shared more frequently after Facebook altered its algorithm to emphasize friends’ posts over publishers’.

Even more damning, a survey from BuzzFeed and Ipsos Public Affairs found that people who use Facebook as their primary news source believed false headlines 83 percent of the time. After initially denying its role in the problem, Facebook addressed it by sponsoring fact-checking initiatives, hiring a media liaison and banning fraudulent websites from its ad network. But that hasn’t been enough to curb the misinformation from spreading.

“While all steps taken by all these entities to curb fake news are admirable,” Bidel said, “as long as fake-news generators can make money from their efforts, the problem won’t go away.”

More in Media

How medical creator Nick Norwitz grew his Substack paid subscribers from 900 to 5,200 within 8 months

Creator Playbook: Unpacking the strategy behind medical YouTuber Nick Norwitz turning to Substack to significantly grow his brand.

Media Briefing: In the AI era, subscribers are the real prize — and the Telegraph proves it

In an era where AI is eroding referral traffic and third-party distribution, a subscriber who pays directly has become the most valuable reader a publisher can own. Springer just bought over a million of them.

Layoffs hit LADbible Group’s social video team amid slower user-generated content growth

Social-first publisher LADbible is in the middle of a second round of layoffs to its social video team, having suffered massive drop-off in Facebook video engagement.