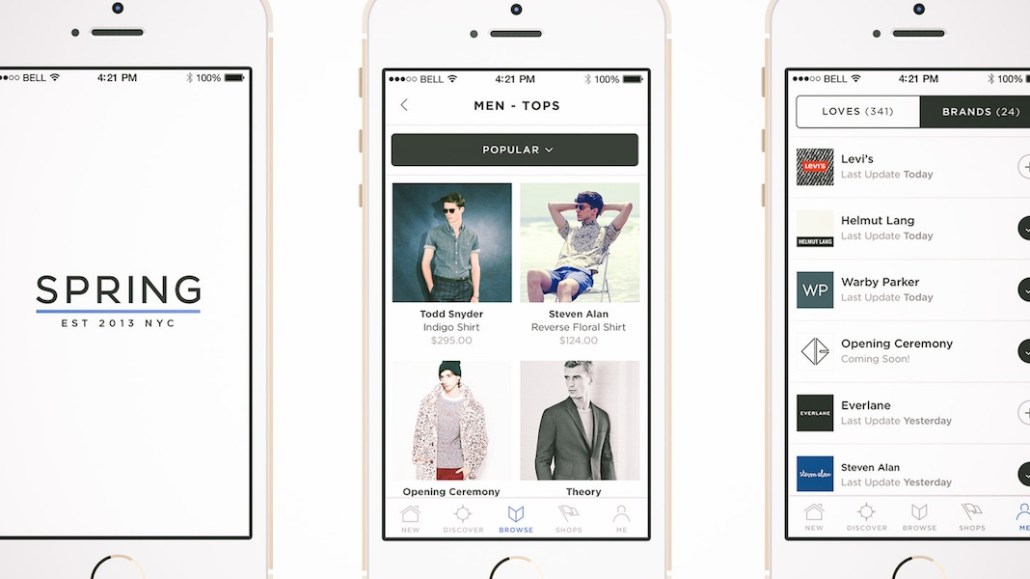

Spring launched in August 2014 with a clear goal: to become the No. 1 mobile shopping app for fashion. Built with user experience top of mind, Spring wanted to make the notoriously difficult mobile checkout seamless: To purchase, customers simply had to store their credit card, then swipe their finger on a product. At launch, 150 brands were on board, including Carolina Herrera and Public School.

Positive press from publications like Vogue and Wired poured in. The verdict: Spring was poised to change the way we buy on our phones.

Today, Spring has 36 million venture capital dollars in its pocket and is said to be seeking more. Up from the launch group of 150, 3,000 brands are now on its marketplace. It has one major app redesign under its belt. According to founder and CEO Alan Tisch, the company has consecutively grown its gross sales by 20 percent month over month, for the past 18 months.

There are cracks, however, in its model.

Spring has shifted away from its mobile-first philosophy, now selling through an e-commerce store. The thousands of brands have turned it into an aggregator, rather than a curator. That stellar monthly growth? Sources close to the company attribute it to constant promotions, a slippery slope for any retailer.

The app that was pitched to brands, investors and customers as the ultimate mobile marketplace for fashion has backpedaled. It has also changed its identity. When asked to say simply what Spring is, Tisch said: “We’re delivering a personal shopping assistant that lets you shop your favorite brands and discover new ones, and offers the best customer experience anywhere, all at the same time.”

So what happened to the app?

The mobile-first marketplace … or maybe not

Founder Alan Tisch, a certified tech guy who launched mobile-facing initiatives like NYC Big App and spent time at flash-sale site Fab, saw the opportunity for Spring in 2013 after feeling “app fatigue.” He knew that while people may download retail and brand mobile apps, the majority of their time is only spent in a handful of apps. He founded Spring as the one-stop mobile marketplace for shopping fashion, grouping together popular brands under one roof and offering easy checkout (no clumsy credit card fields).

The first version of Spring.

But, as many retailers have come to realize as they retire their own mobile apps, acquiring customers in the app space is difficult and expensive. In November of 2015, a little over a year after launch, Spring opened up its e-commerce store.

“The change to focus on e-commerce was a big deal,” said a former employee, who chose to remain anonymous. “We launched a website just to have the web presence without selling, and then a few months later, there was a huge roadmap for our web strategy. Everyone was asking, ‘Are we still app first?’ We were told, ‘We just need to be where the customer is right now,’ and we had to work around that decision.”

While e-commerce is an effective acquisition channel for mobile app users, internal priorities shifted. Web engineers were hired, and after the e-commerce switch was flipped, revenue and traffic sources very quickly moved over to the web, according to multiple past employees. The mobile app, as a revenue and traffic driver, became secondary to the company once said to be creating the first “mobile-first shopping mall.”

Tisch, however, refutes this claim, saying that both traffic and revenue are still “more than 50 percent mobile.”

Going back on its mobile-first premise was like a bait-and-switch for brands who joined specifically for the mobile hook. A representative at a brand, who chose to remain anonymous, said the move to e-commerce diluted Spring’s value.

“The proposition was outlined as a 100-percent app experience on mobile,” said the representative. “When you move away from that, it feels less curated. It was a mobile experiment for us, and now, it’s a question mark as to whether we’ll stay.”

Casting a wide brand net

Spring’s appeal to brands at launch was its free-to-join policy, low commission and promise for mobile exposure and transactions. The initial premise was to create a marketplace that was curated, with a particular focus on lesser-known brands.

As it scaled, however, it drifted away from those early promises.

“It’s too hard to compete with established retailers if you go after the same brands,” said the former employee. “It’s also really hard to stay cool if you go mass — but if you want to make money, you go mass. We started with Public School, then suddenly, everywhere you looked, you saw Michael Kors. There’s definitely a balance between the two, but it’s hard to harness.”

Eventually, Spring shifted its mantra to being a “mobile-led shopping mall.” That meant trying to be everything to everyone, and it quickly swelled its brand partners. Back in 2015, the company said it was adding as many as 15 new brands a week.

“With wholesale accounts, ‘Who else are they selling?’ is a question. When you’re competing in a specific corner of the market, you care about the brand adjacency,” said a brand marketer selling on Spring. “That integrity has to be protected. When we saw who else they were working with, it was, ‘Whoa, it’s everyone.'”

However, the major shift didn’t occur until the company invited retailers, including Saks and Neiman Marcus, to serve as the middlemen.

“A major bump in the road was when we decided to allow retailers on the platform,” said the former employee. “We struggled a lot with that decision, because we had made a promise to the brands that their relationship with the consumer would be direct.”

The employee said that selling wholesale product through retailers on Spring was necessary in order to get brands wary of the platform into the marketplace. By working with existing wholesale retailers, like department stores, Spring could get brands on board without having to appeal to them individually. From Tisch’s point of view, the move was made in order to get brands who do the majority of their sales through wholesale onto the app.

“It felt like we were going back on our promise,” said the former employee.

“Who are you and why do you exist?”

With 3,000 brands in its arsenal, offering a wide range of product categories and price points, Spring’s own identity is hard to determine.

Sources close to the company say that Spring didn’t do enough to carve out a strong point of view. When you become an aggregator similar to ShopStyle and Lyst, who are you and why do you exist?

Spring’s e-commerce store.

“Spring missed out on building a brand at the same time as it scaled growth,” said Ana Andjelic, global strategy director at Havas Lux Hub. “Without a strong perspective, you don’t have customer loyalty. You’re just competing on price. Then you become known as a discount destination.”

A brand that sells on Spring found the retailer’s consistent promotions to be a turn-off.

“We made it very clear we would not participate in those promotions,” the representative said. “When you start going down that road, it’s dangerous. You train your customer. Look at J.Crew.”

The representative added that other marketplaces, like Harper’s Bazaar’s ShopBazaar and Farfetch, have a clear identity, which Spring appeared to lack. Meanwhile, a former employee said that while the company was hitting its monthly sales goals, it was at the expense of constantly putting items on sale and posting promotions to a platform called DealMoon, which is popular with Chinese customers.

Shopping for the next generation

With its eye on the future, Spring’s saving grace is that Tisch has made it clear he’s prepared for slow and steady growth.

His goal is that, eventually, regular users who visit the Spring app or website will get a daily edit of products personalized to their tastes and lifestyles, to help whittle down the overwhelming selection of product. The task, now, is giving customers a compelling reason to keep coming back.

“It’s a really difficult category to innovate in,” said Cheryl Cheng, a partner at Blue Run Ventures. “In fashion, you can’t be utilitarian. People need to remember to come back to you, and that’s built on emotion and loyalty. Net-a-Porter didn’t become Net-a-Porter overnight.”

More in Marketing

YouTube’s upmarket TV push still runs on mid-funnel DNA

YouTube is balancing wanting to be premium TV, the short-form powerhouse and a creator economy engine all at once.

Digiday ranks the best and worst Super Bowl 2026 ads

Now that the dust has settled, it’s time to reflect on the best and worst commercials from Super Bowl 2026.

In the age of AI content, The Super Bowl felt old-fashioned

The Super Bowl is one of the last places where brands are reminded that cultural likeness is easy but shared experience is earned.