Secure your place at the Digiday Publishing Summit in Vail, March 23-25

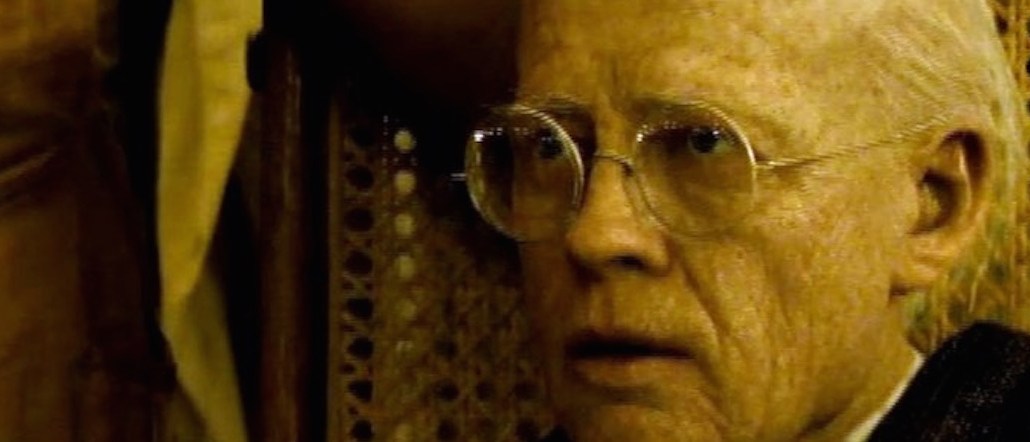

In 2008, John Greiner-Ferris was at work in a Boston-based agency when a co-worker came around with a wagon of beer and Solo cups full of ice. The wagon stopped at every cubicle on the floor except his.

Greiner-Ferris was 53. His co-workers were all under 27.

“It was like a fraternity house,” he said. “I ran through all the reasons in my head why I was singled out. There could be a lot to it. But then I realized there wasn’t, and it was just the most obvious one: I was old, and so I was invisible.”

Greiner-Ferris’ story will come as no surprise to those in the agency world who don’t happen to be a millennial. Over conversations with executives in the agency space, Digiday has been able to discern a growing phenomenon of agency discrimination against employees over the age of 50.

It manifests in multiple ways. For example, agency executives proudly tout how the average age of their shops is a green 27. Another example emerges from the accounts of people who say they were pushed out of agencies when they turned 50 or 55. “Age discrimination is rife against both genders,” said one former agency employee who preferred not to be named.

It’s a two-pronged problem. One, there is an assumption, often wrong, that older employees don’t understand social media. And there’s the fact that younger staffers often just come cheaper.

The growing pace of digital makes people think that older people “can’t do digital” or “don’t get social,” said Greiner-Ferris. In one job interview at a Boston-based shop when he was in his mid-50s, he was asked where he “learned” how to do social media. “It was as if someone was asking me ‘where did you learn brain surgery?’” he said. “Social media is not that hard to figure out.”

One agency executive said shops often want clients to see young people on digital accounts so they feel more “confident” in the company’s abilities. Greg March, CEO of Noble People, said that the benefits of younger employees happen to be both a valid and a convenient excuse. People rave about platforms and how only young people understand them as an excuse. But the truth is, agencies, squeezed by clients, are saying “yes” to lower-margin work. “It puts pressure on raises,” he said.

Everything but age

There’s also the much more obvious “younger people are cheaper” argument. “There is this feeling in this industry that younger is better,” said one agency employee. “And nine times out of 10, it’s driven from a financial efficiency standpoint.” (To be fair, that also cuts both ways: One media agency executive said many CEOs will expect younger people to work for cheap simply because they’re young and then the CEOs take years to promote them.)

It’s actually been a good year when it comes to people waking up to discrimination in the industry. The suit brought by former J. Walter Thompson CEO Gustavo Martinez by his longtime chief communications officer Erin Johnson brought into stark focus deeply rooted issues of sexism and, to a lesser extent, racism, in the industry. More recently, the very public ousting of Publicis’ head coach Kevin Roberts forced a necessary conversation about how far we’ve really come when he claimed in an interview that the gender debate is “over.”

In May, former RAPP U.S. president Greg Andersen sued his employer, accusing then-RAPP CEO Alexei Orlov of wrongful termination, retaliation and discrimination. While most of the attention focused on the sexual and racial harassment Orlov allegedly subjected employees to, Andersen also claimed age discrimination, saying that Orlov told him he “did not want the company filled with people in their 40s or 50s.”

The reference to ageism was made in passing, but it underscores an important point: Gender discrimination is somewhat easier to identify. And for agencies, it’s easy to say that they’re trying to fix it. Racial discrimination is harder prove. And when it comes to charges of ageism, there is a lot of room for plausible deniability.

On the recruiting end, people say it’s no secret that the search process values youth. “Singly, the most undervalued commodity in this business is experience. It’s overlooked in favor of the bright shiny object,” said Jay Haines, founder of executive search firm Grace Blue.

The problem, though, is that youth can’t run a company. Agencies need people who can run a $50 million business, have 15 years of digital experience. But when they hire, they tend to overlook anyone who is 50 or 55. “I see an unconscious bias to hire the young gun or the up-and-comer all the time,” said Haines. Experienced players in his recruiting shortlists are often removed quickly, he said. Often, they end up in “second-tier markets” if they stay in the agency world at all.

Duff Stewart, CEO of GSD&M, puts some of the onus on the older employees themselves. The youth obsession of today’s culture isn’t anything new, he said. The problem is that technology is evolving more quickly — and when some people get to their mid-50s, they get complacent. They start “drifting away” because they don’t keep up.

“You have to push yourself with curiosity and restlessness,” he said. “You can’t get comfortable. We always will need someone who can do great print ads, but we don’t need 22 people who can.” Many of his peers who did not end up in the C-suite moved on and either went to smaller markets or started to teach.

Other than the obvious fact that people should not be discriminated against because of their age, executives also lament the fact that a major human element is lost when older people leave the business. Experience counts for a lot in sticky situations that demand experience. And when older people are cut in favor of younger employees, a key part of the agency-client relationship is lost, said March, who said it takes years to hit grooves with co-workers and client contacts. “If a company can stay focused on higher-margin work, it won’t force them to go as young and it’ll allow them to keep older employees longer,” he said.

As such Christian Hughes, co-founder of Cutwater, said that agencies and employees need to focus on retraining for new skills. “You have to naturally keep yourself current,” he said. “Don’t be like my dad, who used to have his emails printed out.”

Sorry, you can’t sue

Easy enough to say. But people are still routinely let go simply for not being young — and legal action is not usually an option. Robert Ottinger, founder of employment law firm The Ottinger Firm, said that age discrimination is particularly hard to prove. A defense like “young people are cheaper” is actually perfectly legal. There’s also the “bona fide occupational qualification” argument, which employers can use to successfully argue that digital skills are more prevalent among young people. And historically, there’s little precedent: Gross v. JBL financial services, a seminal Supreme Court case in 2009, effectively made it close to impossible to successfully argue age discrimination: “You’d have to argue a systematic replacement of people, so usually it would need a class-action suit,” said Ottinger.

Which is why there are so few age-discrimination cases: Gross v. JBL essentially set a precedent that to sue on basis of age, age would have to be the only cause. It couldn’t be gender and age, for example. That’s one explanation why it’s impossible to put a number on the number of people who have lost their jobs — rightly or wrongly — due to their age, said Ottinger, whose own firm takes almost no age cases.

For Greiner-Ferris, who quit the agency world after almost a decade, it was a no-brainer to not sue. “The people I worked for have a lot of money, and I didn’t have money or time,” he said.

But he acknowledged he’s luckier than many: “My wife has a full-time job, and I have the ability to say, ‘OK, I’ll try something else,’” he said. “There were people I knew who, when they got fired, weren’t as lucky as me.”

Greiner-Ferris is now the founder of the Boston Public Works Theater Company, as well as the artistic director of the Alley Cat Theater Company. “One of my theaters is nationally recognized,” he said. “Guess how I did it? Social media.”

More in Marketing

‘Nobody’s asking the question’: WPP’s biggest restructure in years means nothing until CMOs say it does

WPP declared itself transformed. CMOs will decide if that’s true.

Why a Gen Alpha–focused skin-care brand is giving equity to teen creators

Brands are looking for new ways to build relationships that last, and go deeper than a hashtag-sponsored post.

Pitch deck: How ChatGPT ads are being sold to Criteo advertisers

OpenAI has the ad inventory. Criteo has relationships with advertisers. Here’s how they’re using them.