Secure your place at the Digiday Publishing Summit in Vail, March 23-25

Each month, like clockwork, CNN issues a press release crowing about its “dominance” in digital news and pointing to its comScore rankings, boasting an audience “larger than any other outlet in multiplatform visitors, mobile visitors, video starts, millennial reach and social following.”

One of the core promises of digital media and advertising has always been its measurability. Marketers would finally know “which half of their ad budget was wasted,” and publishers who could build engaged, loyal and sizeable online audiences would be rewarded accordingly.

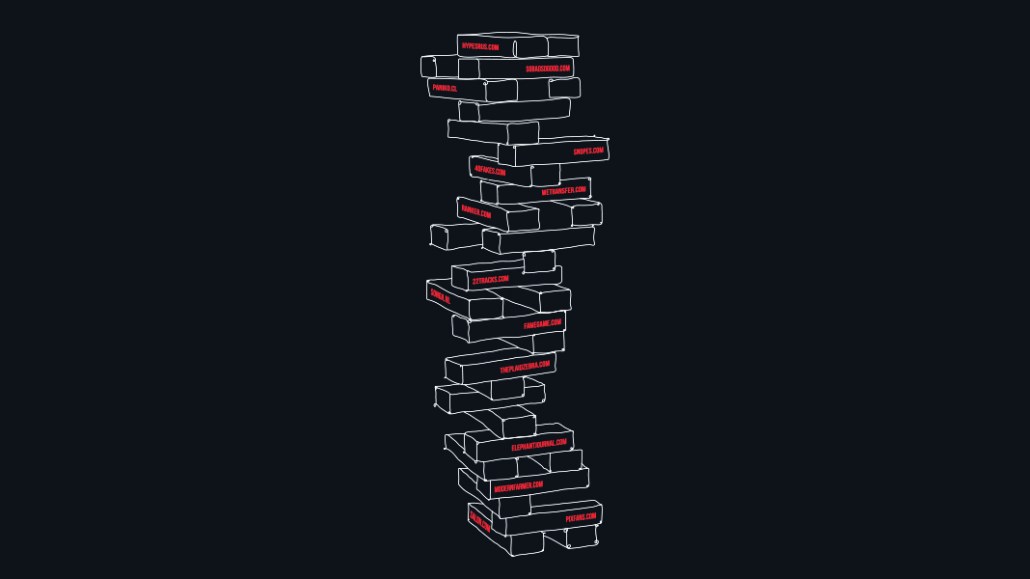

As major audience measurement companies such as comScore — and big platforms such as Facebook and YouTube — gained traction, publishers have spent the past 20 years figuring out how to make their audiences look as large and as appealing as possible — to investors, to advertisers, to business partners and to consumers.

Finding ways to inflate comScore audience numbers has proved perhaps one of the most important and beneficial audience tactics over the past decade, for a variety of reasons. One is that media buyers and advertisers have historically been fixated by comScore rankings, and comScore’s top 100 site list in particular. Even today, many media buyers say they’re frequently asked by clients or by managers to limit their scope to comScore’s top 50 or top 100 list when putting together media plans.

With that in mind, publishers have had every incentive to force their way up comScore’s rankings. There’s a variety of ways to do this, including purchasing traffic from content recommendation services and social networks or from much less-salubrious vendors for a fraction of the price.

One classic technique has been the comScore roll-up, through which a media company or publisher can have traffic from other sites counted towards their comScore numbers, therefore boosting their overall reach. Publishers such as Complex, and Refinery29, Condé Nast and others have used this technique to better arm themselves in pitch meetings with advertisers.

Vice Media is another well-known practitioner of the roll-up. Recent comScore reports show that “Vice Media” reached nearly 70 million uniques in July. Vice.com proper, however, attracted just 27 million, but it was bundled along with traffic from scores of other properties including Salon.com, Banker.com and Snopes.com, among others. Is it technically true that an ad buy with Vice Media could reach 70 million people? Sure, but those people won’t all be on Vice.com.

Vice declined to comment.

According to comScore, this feature was designed to help media companies and publishers sell advertising across networks of sites and properties. “Due to the dynamic nature of content and advertising partnerships within the digital space, comScore had to find a solution that enabled publishers to aggregate together their reach across all of these entities such that they could represent their full reach in ad planning scenarios and pitches,” a company spokeswoman says.

Some ad buyers question how those numbers are presented by publishers and interpreted by the market.

“Experienced digital planners should know the difference, but without digging deep it’s easy to mistake a large ‘property’ with a particular site having high traffic,” says Marcus Pratt, vp of insights and technology at media buying agency Mediasmith. “Vice can come in and say in their pitch deck that they reach almost 70 million monthly uniques.”

Media buying agency The Media Kitchen says it no longer subscribes to comScore, partly because of the tactics publishers employ to force themselves up its rankings.

“The way we approach it now is just working with publishers to test and learn. It’s far more effective than trying to go to someone on the outside, such as a comScore or Similar Web,” says Jonathan Kim, the agency’s digital engineering director.

It’s not just advertisers that are swayed by big numbers. During the digital media investment boom at the middle of the decade, scale was all the rage. Facebook was aiming firehoses of traffic at publishers’ sites, and seemingly the only metric that mattered was who could amass the largest audience, regardless of its quality or loyalty. Investors bought in, at least partly, on the notion that bigger audiences equalled better businesses.

But the world is moving on. Investors and advertisers now realize there’s more to an audience than drive-by traffic, and Facebook, Google and other platforms have decided they’d rather keep their users inside their own walls than lead them off to publisher sites anyway.

Publishers are still welcome to fill the platforms with their content, of course, but only in the form of video that lives natively on those platforms themselves. And as publishers and platforms lean more heavily into video, they’re looking for new ways to boost viewer numbers. Let the games begin.

More in Media

How creator talent agencies are evolving into multi-platform operators

The legacy agency model is being re-built from the ground up to better serve the maturing creator economy – here’s what that looks like.

Why more brands are rethinking influencer marketing with gamified micro-creator programs

Brands like Urban Outfitters and American Eagle are embracing a new, micro-creator-focused approach to influencer marketing. Why now?

WTF is pay per ‘demonstrated’ value in AI content licensing?

Publishers and tech companies are developing a “pay by demonstrated value” model in AI content licensing that ties compensation to usage.