Given the challenges of digital media, commerce is a tempting way for publishers to create new revenue streams by extending their brands. But slapping commerce links on articles can lead to the impression that the editorial side is for sale, damaging the publisher’s credibility.

Some publishers have gotten around this quandary and sell products that are — or on their way to becoming — a meaningful revenue stream. The key is making sure the products are in keeping with the publisher’s brand of journalism. We talked to three of them about their approaches.

The New York Times Store

The Times has been selling Times-branded memorabilia since 1998, but it made a big investment in its retail operation two years ago, hiring an experienced retailer Joseph Adelantar (Links of London, Land’s End) and expanding into other, non-Times-branded items like art, collectibles and high-end housewares. Last year, the Times’ “other revenue,” which includes the store and other brand extensions, brought in 5 -10 percent of total revenue of the Times, up 3 percent primarily through store sales.

The store’s biggest sellers are still the Times-branded merchandise like its birthday book that contains copies of the newspaper’s front page from each birthday of the recipient’s life ($179.95) and Special Day book containing newspaper articles from a given day ($99.95).

But the Times also has had success with products that it sources or creates exclusively through high-end or specialty retailers, like a personalized wooden pie box ($49.95) that sold out in two weeks.

Since the store is meant more to engage with Times readers than to be a big moneymaker, the Times has to be careful to pick items that are in keeping with the brand and match the high quality that people expect of the Times journalism. “I think our readers really look to us to curate items that reflect their lifestyle, so we’re not going to be as commercial in what we do,” said Adelantar, executive director of retail. “The readers did not want us to sell things like apparel or perfume but were open to memorability and tableware.”

Monocle Shop

What started as a service for readers eight years ago now accounts for 17 percent of the revenue for Monocle, the high-end lifestyle magazine started by globetrotting tastemaker Tyler Brûlé. Monocle now has six brick-and-mortar shops from London to New York to Hong Kong that sell exclusive or co-created products for its discerning, mostly male audience — like its Porter Overnighter Bag (£350; “Ideal for a night jaunt to Paris or a long weekend at sea”) or Geografia Sectional Globe (£25; “a perfect tool for you and the youngster to colour in the places you’ve visited while also learning about the earth’s structure”). The products also are sold online here.

Brûlé himself is actively involved in the product selection process. During an interview, he noted he was testing out a pair of slip-ons. About a third of the products Monocle develops are things he finds on his own travels. “There was a very nice leather company in Frankfurt that I came across when I was doing a speech in Germany,” he said. “We went and tracked down the company. They had a business-card-holder-meets-wallet, and based on that, we ended up doing something that was a super slim-line card holder. Something you would take to a cocktail reception that would fit in your pocket and not leave a bulge.” It’s about time.

The revenue is nice, but the store serves other important purposes: The locations can do double duty as an editorial bureau in far-flung cities; provide free advertising for the magazine; and serve as a source of audience intelligence. “We never have to talk to advertisers about audience research,” Brûlé said. “We talk to them every day. We see what they’re buying. It gives us regular, firsthand contact with our buyers.”

Slate Picks

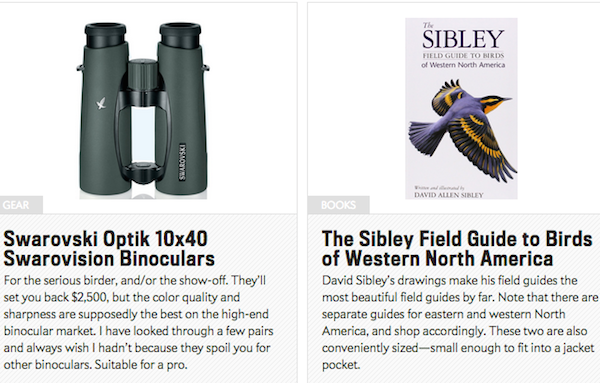

The highbrow news and culture publication makes use of one of its best assets — its well-known journalists — to select the products it sells in its Picks section. Like Oprah’s book club, the idea is that vice chairman and editor-in-chief Jacob Weisberg or senior editor Emily Bazelon can influence sales of products they recommend (like Runner’s World magazine or “Breaking Bad” DVDs, respectively). Readers click through to Amazon and other retailers, which give Slate gets a portion of the sale (typically publishers get 5 percent). Living the Slate life doesn’t come cheap; best-sellers include these $2,500 Swarovski binoculars in Slate’s bird-watching collection and this Toto Washlet ($349.86).

Dan Check, vice chairman of the Slate Group, said Slate is working on how to sell products directly, which enables Slate to keep more of the revenue, and publish recommended collections more often without overtaxing the staff or tread on Slate’s editorial integrity, because “we recognize that the editorial voice is at stake.”

Image courtesy of Monocle.

More in Media

In Graphic Detail: The scale of the challenge facing publishers, politicians eager to damage Google’s adland dominance

Last year was a blowout ad revenue year for Google, despite challenges from several quarters.

Why Walmart is basically a tech company now

The retail giant joined the Nasdaq exchange, also home to technology companies like Amazon, in December.

The Athletic invests in live blogs, video to insulate sports coverage from AI scraping

As the Super Bowl and Winter Olympics collide, The Athletic is leaning into live blogs and video to keeps fans locked in, and AI bots at bay.