Last chance to save on Digiday Publishing Summit passes is February 9

“If you publish good stuff and let people read it, they’ll subscribe.”

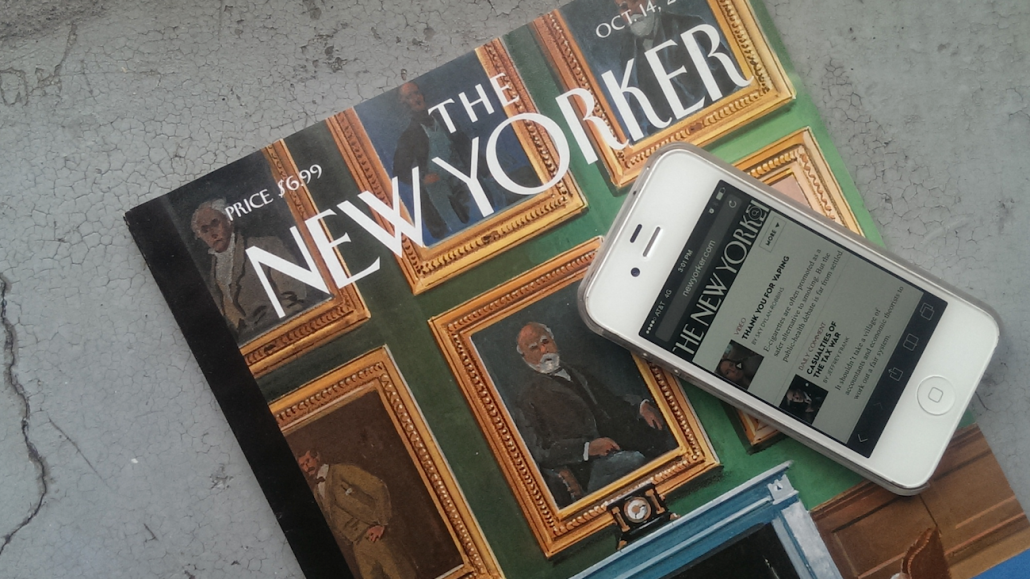

So says NewYorker.com editor Nicholas Thompson, summing up the strategy behind The New Yorker’s new paywall, which went live Tuesday. With the new system, which will let readers read six articles a month before asking them to pay up, The New Yorker hopes to turn some of its most frequent readers into its newest paying customers. The announcement ends the three-month free access period for The New Yorker’s content, which many readers used to binge on articles from the magazine’s archive.

And the strategy’s working. Thompson said that The New Yorker’s subscriber rate actually increased during the free-content period. “Now that we have a paywall and a way to force people to subscribe, we hope that it will go up even more.”

Thompson added that The New Yorker’s paywall, and its six-article limit, the magazine took a particularly data-driven approach to figure out how people were reading and how to craft the most effective paywall for their habits. He explained that, and more, in a recent interview with Digiday. Excerpts:

The New Yorker announced the paywall back in July but finally implemented it yesterday. What’s been going on the last few months?

One of the big reasons we wanted to open up the archive was to see how many stories a month people would read, and to see what kinds of stories people who read to certain levels were reading, and then to try to make our best guess where we should set the meter.

And you landed on six articles a month?

It seemed like it was a number that a lot of people would reach. We also figured that the people who would reach it are also the kind of people who would probably want to keep reading lots of our stuff. Our data suggests that there are tons of people who read more than six stories a month.

So this was all data-driven?

We looked at a couple of things, but yes, data was a big part. If you set the article limit at one free article a month, you may reach many people, but you’re also going to reach many people who aren’t ready to subscribe. You set it at 15 articles, the people you reach are going to be almost certain to subscribe, but you’re not going to reach as many of those people. So we chose six. We looked at the data but also at what feels fair. In the past we used to unlock one feature and two critics’ pieces a week. Now we’re producing all this extra blog content. Does six stories feel right? It’s a balance between the data, what seems fair and what our instinct is.

Were there any other surprises in there?

We have seen if you look at article-completion rates for people who have clicked on links in The New Yorker Twitter feed, the completion rates are pretty high. But if you look at stories clicked on through standard non-New Yorker Twitter feeds, those completion rates are a lot lower. It does show that building that affinity does get people to read stories from beginning to end.

People had fun posting reading lists of archival stuff to get through before it disappears. Did you see those?

It was heartening, this nice Internet meme. But it was a little misguided. It’s not like the stories are locked up — you can still read six a month. If you’re the kind of person who reads more than six stories a month in The New Yorker, but you’re not the kind of person who is going to pay a dollar a week for The New Yorker, we have lots of stuff for you. And that’s a pretty small set of people. Those lists were fun, and I thought they mostly had good taste.

The new paywall treats a shorter New Yorker blog post the same as a magazine feature story that took months to write and edit. Does that devalue magazine content or increase the value of the blog content?

That question was a hard one, and one of the hardest things think through with this process. The advantage of counting magazine stories and blog posts the same is that it’s much clearer and easy to understand. Most people who go to the site don’t know what is a magazine story and what is a blog post. From watching people interact with the site, they treat them more or less the same. It’s simple, it’s clear, it’s easy to understand. But it also shows how much we value the regular blog posts we put up.

Readers treat a 15,000-word piece of reportage the same as a 1,000-word blog post?

It was an interesting conversation, but we decided that simplicity and clarity should win out.

You’re also trying to up the quality of those blog posts, right?

Yes, the percentage of the blog content written by staff writers has gone up over the past few month. That’s very much integrated into this whole decision. Obviously, they’re blog posts. They’re engaging in conversations about things that happened today or this week. They’re not things that a reporter spent six months on. But we’re going to have the same people writing them, and we’re going to have them feel as close as possible to the magazine stories. Your meter will be charged the same either way.

While all of The New Yorker’s articles are behind the paywall, its video content isn’t. What’s the thinking there?

A lot of sites keep their video open. That’s just because advertising rates are so high on videos that we’re just keeping them unlocked.

More in Media

Brands invest in creators for reach as celebs fill the Big Game spots

The Super Bowl is no longer just about day-of posts or prime-time commercials, but the expanding creator ecosystem surrounding it.

WTF is the IAB’s AI Accountability for Publishers Act (and what happens next)?

The IAB introduced a draft bill to make AI companies pay for scraping publishers’ content. Here’s how it’ll differ from copyright law, and what comes next.

Media Briefing: A solid Q4 gives publishers breathing room as they build revenue beyond search

Q4 gave publishers a win — but as ad dollars return, AI-driven discovery shifts mean growth in 2026 will hinge on relevance, not reach.