Secure your place at the Digiday Media Buying Summit in Nashville, March 2-4

Nick Denton, the co-founder of Gawker Media, is known for his penchant for measuring the impact of his blog network. Gawker started rewarding bloggers based on traffic back in 2008 (later switching to monthly uniques). His latest obsession is the company’s sharply increasing revenue growth, which is displayed on a monitor that’s mounted on the main floor of the Gawker headquarters in Manhattan’s Nolita neighborhood.

“Did you see the sales chart?” he says, his voice rising in excitement. “We’re about to hit our target for the whole year.”

Denton is talking to Erin Pettigrew, one of his managers, who readily shares his enthusiasm. Eight years ago, she started as a sales intern; today, she’s vp of business development. And she just may be the second most powerful person at the company.

Pettigrew, 31, oversees Gawker’s e-commerce business, which is driven by a combination of links in editorial articles and posts by a team of writers that work for her. Commerce is one of Gawker’s most important and fastest-growing business segments, accounting for at least 10 percent of revenue. Gawker has generated $52 million in gross sales for retailers year to date this year, surpassing last year’s total. Gawker still gets more than half its revenue from banner ads, but Denton believes the day isn’t far off when e-commerce will account for a third of the company’s revenue, with the rest split between native ad and banner ad revenue.

Pettigrew is the person leading that charge — but she probably isn’t how you’d picture your typical Gawker employee. Completely lacking in the Gawker’s hallmark snark and knowing irony, she exudes professionalism in her demeanor, work ethic and appearance. She has an earnest and serious mien and is prone to making pronouncements like, “We want to figure out how to remove the barriers of telling stories” and “We’re not interested in supporting the old-school latency of storytelling.” On her personal website, she describes how she planned to read an annual report each weekend “to educate [her]self more formally about business at a high level.”

The anti-Denton

In all of this — and more — Pettigrew is the anti-Denton: While he has lived his urbane life in the spotlight publicly embracing a tell-all philosophy, she is reticent. When Denton pushes her to share examples of Gawker’s business success with a reporter, she replies firmly: “I’m not talking numbers.” In an office where scruffiness is the default look, she is invariably polished in a way that wouldn’t be out of place at Hearst or Condé Nast.

“She’s not the stereotypical Gawker employee,” says Ray Wert, who headed Gawker’s car site Jalopnik and who overlapped with Pettigrew at Gawker for seven years. “She’s not a  Williamsburg hipster. She is not, and has never been.”

Williamsburg hipster. She is not, and has never been.”

Indeed, Pettigrew grew up in Lexington, Kentucky, the daughter of two physicians. Home was a thoughtful place of ideas, but she dreamed of going to New York, attracted by its diversity of people and ideas and the sheer size of it all. The Internet became her obsession. She spent her free time in high school the way many girls her age did — writing blogs — and also in ways they didn’t: writing code and learning about Google AdSense and affiliate links.

Indulging in these interests wasn’t merely escapism; it became a means of literal escape. It was by reading online forums that she figured out how to get into Yale. While studying there she worked on the side, fixing students’ computers. After a brief stab at pursuing a dance career in New York — chasing a dream in a move she now characterizes as “regret minimization” — Pettigrew decided she didn’t want to go into a career she knew was “not a growing sector.” So in 2005, she answered a Craigslist job posting for an entry-level position at Gawker.

She was a quick study. Pettigrew moved from intern into ad ops and building sales products. She ultimately added responsibility for business development in 2012, exploring new ad products and revenue partnerships. Among other things, she’s currently experimenting with a new ad format that’s a mashup of native and paid performance advertising. She now even plays a role on the company’s steering committee that deals with questions of company strategy.

But it’s e-commerce where she’s having the most immediate (and visible) impact.

Perhaps just as important, if not more, is that she has Nick Denton’s trust. As much as Denton prizes Gawker’s ability to turn bloggers into Internet stars, he has come to recognize that “the quality I prize more than even intellect is being able to trust someone.” He also noted, “At the core of any organization, you need glue.”

If the talented stable of Gawker writers is the glitter, Pettigrew is that glue. “I want everything to work, but I want it to be simple and elegant,” Denton says. “Sometimes, people I work with best counterbalance that.”

The rise of Gawker

The unlikely ascension of Gawker has become something of publishing industry lore. Denton, now 48, was a little-known outsider when he founded it in 2002. He and his founding editor, fellow flamethrower Elizabeth Spiers, rankled the establishment with unorthodox tactics like paying for tips and outing closeted gay people.

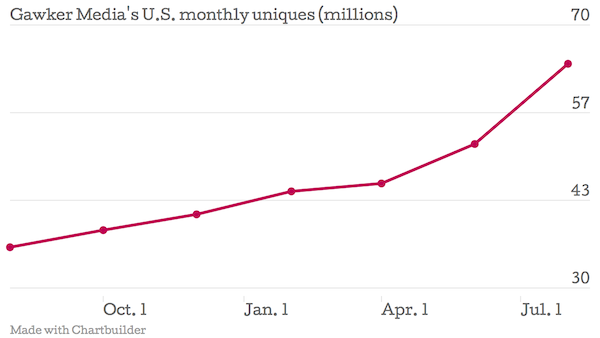

Since then, it has grown from its eponymous media gossip site to a 280-person company with seven other niche sites including Jezebel, Gizmodo and Jalopnik. Collectively, they reach nearly 54 million unique visitors, as of September, according to comScore. That puts the network ahead of stalwarts like The Wall Street Journal and upstarts like Vice and Business Insider and in the company of The New York Times. Gawker still has its mischievous sensibility, with the independent blogger at the core of its business model. But at age 12, it looks and acts increasingly like a mid-sized media company.

Denton is the quintessential company founder — hands-on, even to the point of writing and responding to commenters. Now that it’s a midsize company, he has to loosen the reins if he wants to continue to expand. Denton, for his part, is taking baby steps in this direction. He’s recognizing a new level of managers like Pettigrew, acknowledging in a recent company newsletter the need for patience and pledging to give only “minimal guidance” for an upcoming project. “I have to stop being in control of every single pixel,” he says. The company even has an operating committee now, the closest it has to a management group.

In Pettigrew, Denton has found someone who can both champion his projects and figure out how to see them through. “It’s a rare quality – someone who likes ideas and is practical,” he says of her. Pettigrew echos Denton’s fiscally conservative ethos, saying things like, “I don’t want to be buying candy we don’t need to eat” and “constraint breeds creativity.”

“It’s continued to be a fight tooth and nail for him to let anything go,” said Ray Wert, who headed Gawker’s car site Jalopnik. “When people push back, he grows frustrated. One thing Erin has done an excellent job at is finding an area of untapped potential that is in line with Nick’s overall goal and pursuing it with gusto. She’s done an excellent job of setting the expectation bar with her projects in such a way that there isn’t a lot of pushback. Nick’s never going to fully give up control of Gawker Media. But if he were to, Erin would be the best candidate for CEO.”

Denton maintains he has no plans to turn over the company. “I don’t think about that,” he says. “I do think about setting up the company to continue to grow at the pace we have, or even faster. I want us to have an impact on the way people communicate online.”

Beyond the banner

A few years after founding Gawker, Denton realized, as did others, that he had to think beyond the standard display ad. Ad and click-through rates for those ads were plummeting. A new wave of competition was growing up around him, starting with companies like Engadget, TMZ and Weblogs, and later intensified by VC-funded news sites like Vice, Vox and BuzzFeed. “If we’re going to survive here,” he told himself, “we need to behave more like a company, a professional organization.”

Like many publishers, Denton joined the stampede for native advertising. He created a content division within the advertising department that would work with clients to create editorial-like ads, and, unusually, assigned an editor, Jalopnik’s Wert, to lead it (Wert has since left to start Tiny Toy Car, a digital ad studio, but continues to stay involved with Gawker, which is a client).

Denton then raided that quintessential prestige media company, Condé Nast, for his head of sales, Andrew Gorenstein. He has begun expanding internationally through partnership agreements. And he has expanded the company’s reach into e-commerce.

With ad revenue hard to come by online and even more so in print, commerce is an area other premium publishers have tried to tap into. That doesn’t mean they’ve had much success at it.

For starters, the two goals are fundamentally at odds; publishers ultimately want their readers to stick around, while driving commerce means sending them off the page to make a purchase. Few publishers want to go all in and get into the business of being retailers. So most settle for the standard (and low-risk) revenue-share model, where publishers get only a tiny portion of each sale. The commission varies widely depending on the product category, but according to Skimlinks, a third party that manages e-commerce for publishers including Gawker as well as Time Inc. and Hearst, the average cut its publishers receive on a sale is 5 percent.

Then there are editorial risks. Publishers have long recommended products to readers, but once they start to receive a cut of the sale, their motives become subject to scrutiny. (The Washington Post found this out when it awkwardly inserted “buy it now” buttons into news articles, including, most notably, one about a controversial new cover for the book “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.”) So it’s no wonder few publishers have made e-commerce a significant source of their revenue.

Gawker’s foray, led by Pettigrew, is a notable industry exception. The company drives people to purchase, then collects a cut of the sale. Buy buttons are included in editorial articles like this one on “geek tools” that take people to retailers like Amazon, Walmart and New Egg, as well as “Deals” and “Sponsored” posts produced by Pettigrew’s commerce team of writers like this one featuring deals on home goods.

All this happened somewhat serendipitously. Gawker Media first started using e-commerce links on Gizmodo, its gadget site. Gawker was using its publishing platform Kinja to surface relevant links within articles. Once Denton realized that Kinja could also be used to plug relevant e-commerce links into posts they began to appear regularly on Gawker’s other blogs like car-focused Jalopnik, gaming site Kotaku and Lifehacker.

“When we started working with them, they were resistant for a while,” says Skimlinks co-founder Alicia Navarro of Gawker’s use of commerce links to drive editorial and native content. “Then they became easily leaders in the space. They were the first to create process and structures around optimizing it. And they’ve reaped the reward.”

Denton may have put Gawker on the map by eviscerating public figures like Rupert Murdoch and Rob Ford, but these days, he’s just as excited about how his blogs drive people to purchase. Pettigrew says Gawker’s conversion rate (defined as the percentage of people who complete a purchase after clicking an e-commerce link) is 8 to 12 percent, compared to 4 to 5 percent for Amazon. (Independent research puts the overall e-commerce conversion rate at 2 to 3 percent.) Denton chalks that up to Gawker’s editorial credibility and its product recommendations.

“Our performance is better because there’s a kind of credibility,” he says. The conversion rate, Denton says, “may be my absolute favorite data point, because it may be the only thing that shows virtue is rewarded. That, more than anything, makes me believe this is a long-term, viable financial business model that isn’t going to be dependent on the vagaries of banner advertising.”

Growing its commerce revenue will mean scaling those buy links throughout the network, which won’t be without its challenges. Commerce links are most natural on sites that cater to people when they’re in a buying frame of mind, which is why they’re most prevalent on blogs like Lifehacker, Jalopnik and Gizmodo. That presumably would make them less suited to sites like feminist blog Jezebel and the flagship Gawker. Gawker could risk losing some of its edgy sensibility if it takes the practice too far. It’s one thing to see gadgets pop up on Gizmodo, but the occasional sewing machine and pots and pans can seem out of place.

But Denton waves off such concerns. Jezebel and Gawker carry plenty of cultural and entertainment coverage that’s suited for e-commerce. “From an editorial standpoint, I’d like to have more service journalism,” he says. “I don’t think there’s anything inconsistent with that.”

In a sense, that defiance remains true to Gawker’s origins. Denton prides the company on being independent, in contrast with his rivals that are “drunk” on VC financing. The line is that being independent gives Gawker more editorial freedom than it would have if it were beholden to outside investors. “We pay our bills on time.” Yet he admits there are constraints: “We don’t do prestige projects. We can’t afford to.”

Gawker isn’t above blatant traffic ploys, either, as in with A Compilation Of People Fucking Up The Ice Bucket Challenge, which got more than 16 million hits. But all in moderation. “We don’t do as much as BuzzFeed,” Denton says. “We play the Facebook game, too. But we don’t do it with the same enthusiasm.”

For now, it’s good to be Pettigrew. Fresh from a sabbatical and honeymoon, Denton is planning Gawker’s physical move into posh Union Square digs next spring, the most external sign of his empire’s growth. And Pettigrew, having grown up at Gawker, understands Denton as well as anyone and has come around to his risk-taking ethos, without losing her firm grip on the details of executing programs.

Back at the Gawker headquarters, Denton has a chuckle at Pettigrew’s expense.

“You thought commerce was a risk,” Denton says to her of her earlier Gawker days.

“There’s a side of me that wants to do it more,” she replies, reflectively. “You have to do it, or else you’re going to stagnate.”

More in Media

Media Briefing: Turning scraped content into paid assets — Amazon and Microsoft build AI marketplaces

Amazon plans an AI content marketplace to join Microsoft’s efforts and pay publishers — but it relies on AI com stop scraping for free.

Overheard at the Digiday AI Marketing Strategies event

Marketers, brands, and tech companies chat in-person at Digiday’s AI Marketing Strategies event about internal friction, how best to use AI tools, and more.

Digiday+ Research: Dow Jones, Business Insider and other publishers on AI-driven search

This report explores how publishers are navigating search as AI reshapes how people access information and how publishers monetize content.