Secure your place at the Digiday Publishing Summit in Vail, March 23-25

The digital video industry has a lot going for it: online video viewership is rising, advertising budgets are growing to match and big media players are acquiring digital content networks like Fullscreen and Maker Studios for hundreds of millions of dollars.

And yet, there are reasons to temper optimism, especially when it comes to digital video matching the enduring power of television, both with consumers and with big brands. We spoke to experts and crunched the numbers to debunk popularly held digital video myths.

Myth 1: Online video ads challenge the scale of TV advertising.

Digital evangelists have forecasted the impending “death of television” for years, pointing to young people who’ve cut out cable in favor of online video sources.

But in 2014, television remains a dominant force in the advertising landscape, with a scope and scale unrivaled by popular Web video portals like YouTube. In a June 2014 report, RBC Capital Markets analyst David Bank stated “the online video market poses little threat to the traditional network TV ecosystem.” To highlight the drastic contrast between the two markets, Banks asserted the advertising value of an entire week of YouTube viewership is equivalent to that of a single, first-run episode of CBS sitcom “The Big Bang Theory.”

“Is ‘The Big Bang Theory’ a big show? Yes,” said Bank. “Does its scale threaten the fabric of the rest of the TV advertising ecosystem? We do not think so.”

A “Big Bang” viewer sits through around eight minutes of advertising, while a YouTube viewer is exposed to far shorter, less frequent pre-roll ads, some of which can be skipped. Moreover, Bank noted, only around 16 percent of ad minutes in online video run against premium content, and roughly half of that inventory is available on properties owned by major media companies like CBS or ABC. Not accounting for those players, total advertising minutes for premium Web video inventory is less than 1 percent of cable networks’ inventory.

“If Winston Churchill had been a media planner, he would have said that television is the worst form of advertising except for all others that have been tried,” Pivotal Research analyst Brian Weiser told Digiday.

Myth 2: Digital marketing budgets are decimating the traditional media spend.

Some marketers shift resources from channels like television or print to increase their digital video ad budgets, as a recent study from AOL Platform’s Adap.tv shows. But another pair of reports suggests that digital spending isn’t cannibalizing traditional media spending by an increasing margin each year, as is widely believed.

The 2014 SoDA report from the Society of Digital Agencies, which surveyed digital marketers at brands, agencies and production studios, found a smaller group of client-side respondents are siphoning funds from traditional to digital budgets this year than in 2013. In the 2013 survey, 39 percent of client-side respondents said they were growing their digital marketing budgets by piping money from their traditional media budget, while only 25 percent of client-side respondents this year indicated they were piping resources from traditional to digital.

Duke University’s semi-annual CMO survey, meanwhile, shows CMOs predicting continued growth in digital and slight declines in tradition ad spending — but the trend for the past three years contradicts the notion that digital budgets across the board are swelling exponentially.

Myth 3: Web video inventory is nearly limitless.

Contrary to popular belief, the Internet does not offer unlimited video advertising opportunities. That was news to political strategists across the U.S. who sought to buy ad space on YouTube or other Web video platforms for the upcoming election, only to find out that the inventory they wanted was already booked.

On YouTube, “reserve buys” — pre-roll ads that can’t be skipped — are finite. Three weeks away from election day, YouTube’s reserve-buy inventory in battleground states like Alaska, Maine, Montana and New Hampshire is nearly gone, according to The New York Times. It’s a similar story at video hubs like Yahoo, Hulu and top news sites.

“Many political strategists don’t think of the Internet as something that can sell out,” Rob Saliterman, YouTube’s elections team chief, told the Times. “But in these smaller states, just as there’s a finite amount of TV inventory, there’s a finite amount of YouTube inventory.”

Myth 4: Online video accounts for nearly 10 percent of total video consumption.

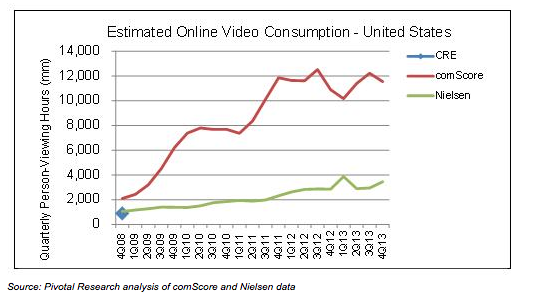

Data from measurement firm comScore states that roughly 9 percent of total video consumption happens online. That’s a far cry from Nielsen’s estimate, which is closer to 3 percent. Pivotal Research believes Nielsen’s total is much more precise.

There are a number of differences that could account for the stark contrast, like devices measured, but the largest one is likely methodology. The Nielsen data is passively collected, while comScore’s is actively solicited from survey respondents.

“When forced to choose between two sets of researchers and methodologies,” Weiser wrote in a March 2014 research note, “we would want to put more trust in a body that has experienced decades of collaboration with stakeholders, not to mention decades of institutionalized experience in research methodologies relating to seemingly mundane spheres as how to recruit a panel or how to ensure that biases are not built into a sample. … The trends implied by comScore always seemed unlikely to us.”

More in Media

In graphic detail: Middle-tier creators are fueling the next phase of the creator economy

Facts and figures behind the growing middle tier of creators who make less than macro creators, but convert more.

How medical creator Nick Norwitz grew his Substack paid subscribers from 900 to 5,200 within 8 months

Creator Playbook: Unpacking the strategy behind medical YouTuber Nick Norwitz turning to Substack to significantly grow his brand.

Media Briefing: In the AI era, subscribers are the real prize — and the Telegraph proves it

In an era where AI is eroding referral traffic and third-party distribution, a subscriber who pays directly has become the most valuable reader a publisher can own. Springer just bought over a million of them.