Secure your place at the Digiday Media Buying Summit in Nashville, March 2-4

A History of Ad Tech Chapter 2: The Ad Net’s Golden Age

This is part of a series that explores the once lucrative and tumultuous ad tech industry. More from the series →

The online advertising business of the 1990s was a bubble fueled by venture capitalists eager to make the most of the online land grab. Although, the bursting of the dotcom bubble in 2000 arrested the “hockey stick growth” of online ad spend, not to mention investment in companies providing such services.

Arguably, the opening decade of the 21st century was pivotal for ad tech as society’s digital transformation went underway; Big Tech embraced advertising as a business model, and some of the most enduring businesses in the sector were founded. And, in a decade of highs and lows for the sector, the broader economic crash of the latter half of the 2000s helped fuel the rise of programmatic advertising.

The crash

Per Martin Kihn, a noted industry analyst, best-selling author, and podcaster, the decline of the broader digital sector had a gravitational pull on the fortunes of digital advertising. However, the botched merger of AOL and Time Warner solidified its malaise for years.

“AOL acquired Time Warner [in a $182 billion deal], and that just seemed ridiculous,” he says, adding. “There was this shady subscription [given its relatively unknown status in corporate America] ISP acquiring this 100-year-old empire, even at the time people said it was absurd, nothing was making sense.”

Kihn further notes, “That was the peak; everything started to fall from that point.”

The stock price of several ad tech companies that listed on the public markets during the initial wave suffered; even ad tech’s talisman DoubleClick felt the chill while others didn’t survive, such as web portal Excite (it went bankrupt in 2001), but there were some notable survivors.

Kihn points to 24/7 Media — a company that listed on the Nasdaq three years after its founding in 1995 and later merged with Real Media in a reported $2 million deal in 2001 — as an example of the survival instinct necessary to make it through such a baron time.

“That was an amazing story; they were going to go out of business; it was a near-death experience,” he notes while alluding to its 2007 purchase for $650 million by agency giant WPP. “They all wanted to quit in 2001, but [24/7’s CEO] David Moore wanted to keep fighting and said never give up.”

The recovery & the Golden Age of ad nets

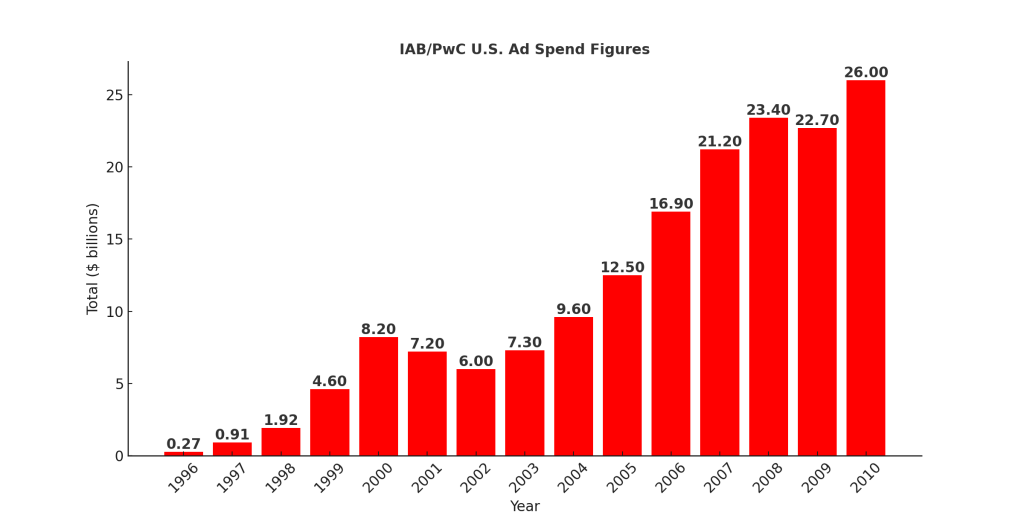

An examination of the IAB’s ad spend figures demonstrates just how steep and long the decline of the online ad industry was when compared with the halcyon days of the 1990s.

Spending dropped for two successive years after tipping the $8 billion mark in 2000, with growth rates only starting to resemble their 1990s growth levels in the mid-to-late part of the decade, see chart.

For Marketecure’s Ari Paparo, a serial entrepreneur in the space who joined DoubleClick in 2004, the early 2000s was the prime era for selling online media space via ad networks.

The value proposition of ad networks was helping publishers generate net new revenue.

“Ad networks existed from the earliest days of digital advertising because there’s this power law of distribution with the way publishers act,” he explains.

“You have the biggest publishers that get all the attention, and then you have this long-tail [of media owners], so there was a role for companies like 24/7 and DoubleClick to bundle up inventory and represent them to advertisers.”

For example, ad networks of the era included Specific Media (which now sits within Viant), BlueLithium (purchased by Yahoo for $300 million in 2007), and Ad.com (bought by AOL for $435 million in 2004).

Meanwhile, as the baron days of the early 2000s continued, and ad inventory prices were minuscule compared to the highs of the 1990s, ad networks shifted toward a performance marketing offering.

“That’s when you started to see the golden age of the ad network,” says Paparo. “You had a lot of these companies buying very cheap inventory, then using data and algorithms to take the cheap crap and turn it into gold for advertisers.”

Other reputed proponents of this model during the era were AdMob (purchased by Google in 2009 for $750 million), Quattro Wireless (purchased by Apple in 2010 for $275 million), Interclick (purchased by Yahoo for $270 million in 2011) and Undertone (purchased by Perion Network in 2015 for $180 million).

However, this golden era was one whereby publishers were often left shortchanged as transparency for buyers and sellers was an afterthought.

“The ad network could take enormous margins,” observes Paparo. “If both sides [of a media buy] were happy, everything got taken by the ad networks.”

Big Tech’s M&A run & the rise of programmatic

Industry observers also point to the (comparative) developing nature of the search advertising sector, given that Google launched AdWords – the industry’s most successful search advertising offering – in late 2000, as one of the reasons why high-margin ad networks were able to proliferate.

Meanwhile, as Google laid the foundations of its advertising empire in the early-to-mid 2000s – as it IPO’d in 2004 – executives at its (then) search engine rivals AOL and Yahoo also had their heads turned by the ad network model, as evidenced by their above-mentioned purchases in the field.

However, it was 2007 that became a pivotal year for the broader sector as the scions of Big Tech grew ever more acquisitive of ad tech.

In this passage of history, Google’s ascent to the pinnacle of the advertising industry is genuinely underway with its notable M&A activity, including the $1.65 billion purchase of YouTube in 2006.

While the name DoubleClick may not have had the name-recognition of the online streaming service YouTube, Google would pay almost double the amount ($3.1 billion) for the ad tech player in a deal that had to be cleared by the U.S. Congress in 2007.

During the intervening years, DoubleClick delisted from the Nasdaq in 2005 (this was part of the post-crash recovery plan of its PE owners’ Hellman & Friedman) and added several strings to its initial ad server offering.

The birth of programmatic

Ciarán O’Kane, a partner at investment firm First Party Capital, notes how the DoubleClick purchase – later complemented by Google’s 2010 purchases of SSP AdMeld for $400 million and Invite Media for $80 million – was a fundamental shift for the industry.

“Google was going to change the entire way that inventory was traded [with these deals],” he says. “They saw a huge opportunity to build an automated system.”

At that point, Google was not the only Big Tech player on the acquisition trail, with Microsoft acquiring AdECN – a company whose C-suite included the (then) little-known Jeff Green – for a reputed $70 million in 2007. This amount was a rounding error compared to the $6 billion Microsoft spent on fellow ad tech company aQuantive during the same year.

Not to be outdone, Yahoo also dug deep into its pockets for ad tech that year with its $680 million purchase of Yahoo. “That year, things really started to accelerate,” notes O’Kane, “And that’s when things started to change in terms of how media was executed.

Both O’Kane and Paparo (the latter of whom served as vp of rich media at DoubleClick throughout this era) note how the ad exchange offerings of all three ad tech companies proved attractive to their suitors that year.

The emergence of the ad exchange – Right Click Media CTO, and later AppNexus cofounder Brian O’Kelley is widely credited as the creator of such technology – during this era is regarded as revolutionary by most seasoned industry observers.

Initially, ad exchanges helped ad networks more efficiently trade their inventory with other aggregated sources of inventory supply, but this initial benefit was to come with later consequences, note observers.

“Right Media was effectively an ad server for ad networks,” explains Paparo, noting how (at this time) the Yahoo-owned technology operated more efficiently than DoubleClick’s ad exchange.

“This meant a single ad impression could be swapped between ad networks, which was great for ad networks as it made their supply and demand more efficient, but most ad networks didn’t realize that it was the beginning of the end for them.”

Paparo points to how the emergence of ad exchanges meant buyers and sellers, i.e. the companies that had formerly been blissfully unaware of the vast margins ad networks made, could eventually take more control, hence Big Tech’s interest.

“People realized that with the invention of the ad exchange, it could potentially transform [the media industry that formerly bought and sold ad space face-to-face] and become more like Wall Street. Any buyer could transact with any seller on the fly with their data in an optimized way,” he observes.

“For big companies like Google, Microsoft, and Yahoo, this was a huge opportunity, as they were already going this within their Walled Gardens. By owning an exchange, they could capture all kinds of media they weren’t already.”

Into the 2010s …

Away from the major M&A moves from Big Tech, 2007 also saw the founding of several of the most iconic independent ad tech companies with O’Kelley exiting Right Media after its Yahoo purchase to form AppNexus.

Meanwhile, terms such as ‘demand-side platform’ became popular with MediaMath (2007) plus The Trade Desk (2009) entered the fray. Simultaneously, their mirror image counterparts ‘supply-side platforms’ like Rubicon Project (better known today as Magnite), OpenX, and PubMatic all launched in 2007.

In the years to follow, such independent players benefitted from the macroeconomics generated in the wake of the global financial crisis of 2008, as VCs sought to put their ‘cheap money’ to work and take on Google et al. Similarly, an industry-wide appetite for thrift engulfed the media industry, and many saw ad tech as just the tonic, with media agencies increasingly taking the role as primaries in media trades in the 2010s.

This is the second in a series examining the history of ad tech. To read the full series, view here.

More in Media Buying

Future of TV Briefing: CTV identity matches are usually wrong

This week’s Future of TV Briefing looks at a Truthset study showing the error rate for matches between IP and deterministic IDs like email addresses can exceed 84%.

Canadian indie Salt XC expands its U.S. presence with purchase of Craft & Commerce

Less than a year after buying Nectar First, an AI-driven specialist, Salt XC has expanded its full-service media offerings with the purchase of Craft and Commerce.

Ad Tech Briefing: Publishers are turning to AI-powered mathmen, but can it trump political machinations?

New ad verification and measurement techniques will have to turnover the ‘i just don’t want to get fired’ mindset.