Secure your place at the Digiday Media Buying Summit in Nashville, March 2-4

‘In China you have to use it’: How WeChat is powering a mobile commerce boom

A diner eats with a group of friends and splits the check by sending a QR code out to his party — each of whom can automatically pay their portion of the bill with the tap of their phones. That same diner can use that very same app to buy movie tickets after dinner — and then hail a cab home at the end of the night.

That’s not all, either. The same single app lets him create a pair of custom Nikes, send an order to the nearest Starbucks, browse Burberry’s latest runway collection, count the number of steps he takes each day, plan a family vacation, upload and share photos with friends, order delivery, host a conference call and keep up with the news.

While such an app sounds implausibly futuristic, for WeChat’s 600 million monthly users, the seamless experience is a daily fact of life. WeChat, founded by Tencent in 2011, has built an infrastructure for mobile commerce within the walls of a singular app, simultaneously catering to the mobile-first consumers of China and solidifying its leadership in the same market, one that far outpaces the U.S.

“It’s an ecosystem,” said Yichi Zhang, a Chinese native and co-founder of the agency McGann-Zhang, which has offices in both Beijing and L.A. “In China, you have to use it.”

Zhang said that WeChat’s user experience is what developers in every industry in the U.S. — from tech, to publishing, to retail — are striving to build on mobile.

“They’re doing things we’re simply not doing in the U.S.,” said Brian Buchwald, CEO of consumer intelligence firm Bomoda. “Imagine if you were going to start a city from scratch. Rather than having to deal with all the infrastructure created 200 years ago, you could hit the ground running on the latest technology. That’s what China’s doing — they’re accessing markets for the first time through mobile apps and payments.”

China’s mobile-first consumers

Mobile commerce in China grew simultaneously with e-commerce, which became ubiquitous in the mid-2000s, when China’s major online marketplace, Alibaba, launched its e-commerce store Taobao. Consumer behavior in China is the inverse of what it is here: In the U.S., research tends to happen on mobile while purchases take place online; those in China who own desktops will do research then look to their phones to make actual transactions.

In lieu of credit cards, two major online payment systems have emerged as China’s major facilitators for m-commerce transactions: Alipay, owned by Alibaba, and mobile messaging platform WeChat’s mobile wallet, WeChat Wallet.

“There’s a battle between Alibaba and WeChat to make the easiest, most integrated payment system in the world,” said Buchwald. “Alibaba’s advantage is being the world’s largest marketplace. It was around before WeChat, but it’s a desktop-first product. WeChat was built with a mobile-first mentality.”

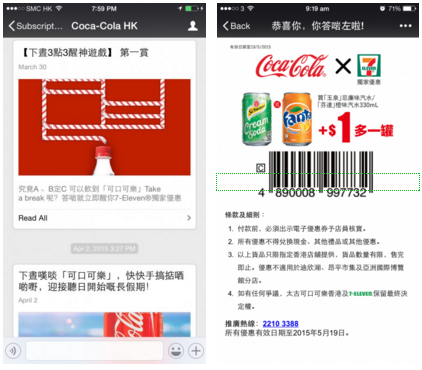

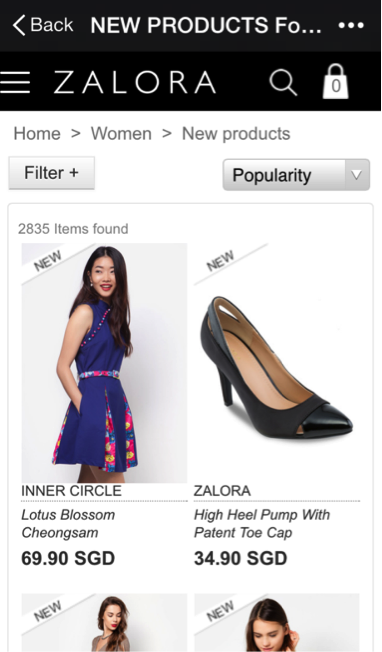

To compete with Alibaba, WeChat has been stitching together a mobile marketplace for service and product-driven companies. According to Zhang, the mobile checkout process can be as simple as scanning a QR code, a prominent facilitator for transactions in WeChat. Retailers like Yoox and Zalora have fully functional mobile stores built into the app. Taxis can be booked, bills paid and products purchased with a few taps.

“The payment process is seamless. It takes 30 seconds, and you don’t get out of the app at any point,” said Zhang, who pointed out the laborious steps that could rack up precious minutes spent on mobile in America — searching online, opening a mobile Web browser, entering credit card information or heading to PayPal, all the while bouncing between apps and tabs.

China’s mobile commerce market has greatly eclipsed that in the U.S., with China’s mobile sales outnumbering the U.S.’s by 450 percent. According to an eMarketer study done in July, mobile spending in China is expected to hit a global record high in 2015 of 49.7 percent of all e-commerce in the country, with projections for 2019 setting the percentage of mobile commerce transactions at 71.5 percent of all online retail.

This year, eMarketer expects m-commerce purchases will total 22 percent of all online sales in the U.S., and it’s much slower growing. By 2019, eMarketer predicts the percentage of mobile sales will inch up to 28 percent.

Building a mobile home for big brands

In 2012, WeChat opened up its platform for businesses to create official accounts; McDonald’s China was the first to join in. Initially launching coupons and branded games, McDonald’s started accepting WeChat payments in 2015 on a small scale, to sell a special line of toys. At the end of this year, the company expects to roll out the payment option for all of its products. In McDonald’s mobile WeChat store, customers can also order delivery and locate stores, according to Regina Hui, director of communications for McDonald’s China, who added that McDonald’s has 6.3 million fans on its WeChat account. Fans are akin to followers.

“Apart from distributing news, we offer also tailor-made promotions for our fans, and it’s become an important CRM platform for us,” said Hui. “When WeChat payment is fully available, the data behind will become even more comprehensive and powerful.”

Other brands that have joined WeChat’s marketplace to connect with users include Nike, Burberry, Starbucks and Coca-Cola. For sneaker companies, luxury designers and beverage companies, WeChat’s broad and engaged user base represents a goldmine of untapped data.

That mobile consumer data is not something to overlook, considering just how much time the country’s population spends on the mobile Web: 87.4 percent of China’s Internet users regularly access the Internet via phone. In the U.S., 74.6 percent of Internet users access the Web over the phones, according to eMarketer data.

“There’s a big cultural difference in terms of consumption habits between the U.S. and China,” said Haixia Wang, eMarketer’s Asia Pacific analyst. “In China, people are eager to try and experience, and they’re not stuck in certain habits.”

Rivaling China’s mobile dominance

In the U.S., one-tap mobile payments have been introduced by Facebook, Pinterest, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube and Google. Individual retail mobile apps, like Amazon, Sephora and Macy’s, offer simple transactions for those who are willing to download, keep credit card information on file and frequently shop within the app. But there is no one-stop shop.

The proliferation of buy buttons means that adoption has been slow, with different solutions jostling to become the mobile user’s one-tap checkout of choice. ApplePay is the closest answer to WeChat Wallet and AliPay, but in June, 33 percent of iPhone 6 users reported using the service at checkout where it was available, according to a survey by Pymnts.com. That percentage had fallen from 48 percent in March.

One system, however, could imitate WeChat’s capabilities in the U.S. In the past year, Messenger has evolved from a Facebook feature to a standalone app — to a blossoming platform. An army of comparable features include apps-within-the-app, like payments, voice and video calls and an equal monthly active user count of 600 million. According to Mark Zuckerberg, it’s a “platform of the future.”

Nir Kshetri, a professor at the University of North Carolina’s Bryan School of Business and Economics, said that WeChat’s biggest strength is its retention. Where Alibaba surpasses WeChat in terms of transactions — facilitating about 50 billion per day — WeChat’s 600 million monthly users give it an advantage, especially around consumer data and behavior.

Those numbers are eye-popping, and some are speculating that, due to its saturation, China’s e-commerce market will be surpassed by another burgeoning region: Southeast Asia. Sheji Ho, CMO of e-commerce solutions provider aCommerce, wrote that the region is mobile-first — more so than even China — with a trajectory to grow even faster than China’s.

Ho added that while Southeast Asia is a promising region for m-commerce, it still has room to improve: User experience isn’t where it needs to be for the mobile-first consumer.

Technological advancements in China, however, are still barreling ahead. Zhang said that Alipay is testing payments by physical recognition — technology that enables shoppers to check out at a store, even ones as generic as the supermarket, by scanning a distinct physical feature, like a tattoo.

In the U.S., while the kinks of mobile UX are still being ironed out across all apps, mobile-first users are just arriving.

“I have a daughter who’s 17 months old, and I watch her on the iPhone,” said Buchwald. “She’s much more in tune on it than I am, and when she’s 10 years old, she’ll never know anything other than electronic and mobile payments. That’s where the Chinese consumer is now.”

More in Marketing

WTF are tokens?

When someone sends a prompt or receives a response, the system breaks language into small segments. These fragments are tokens.

AI is changing how retailers select tech partners

The quick rise of artificial intelligence-powered tools has reshaped retailers’ process of selecting technology partners for anything from marketing to supply chain to merchandising.

YouTube’s upmarket TV push still runs on mid-funnel DNA

YouTube is balancing wanting to be premium TV, the short-form powerhouse and a creator economy engine all at once.