Secure your place at the Digiday Media Buying Summit in Nashville, March 2-4

Greg Hankerson, founder of Phoenix-based boutique furniture company Vintage Industrial, has been fighting plagiarized designs on Alibaba’s platforms, especially Taobao, for the past two years. Hankerson first got in contact with Xinghao Wang, senior manager of intellectual property protection and innovation for Alibaba, in August of 2016 when he complained that Alibaba’s intellectual property protection reporting system didn’t work and suggested that the media would cover his unpleasant experience on the platform.

That November, Hankerson sent Wang 404 listings for products that he believed were counterfeits and another 397 listings last March. To date, Alibaba has taken down around 20 percent of the product listings he reported, according to Hankerson.

“Wang was willing to help, but the counterfeiting situation is not getting better on the Alibaba platforms,” Hankerson says. “When you take two plagiarized photos down today, you find another four the next day, which is frustrating.”

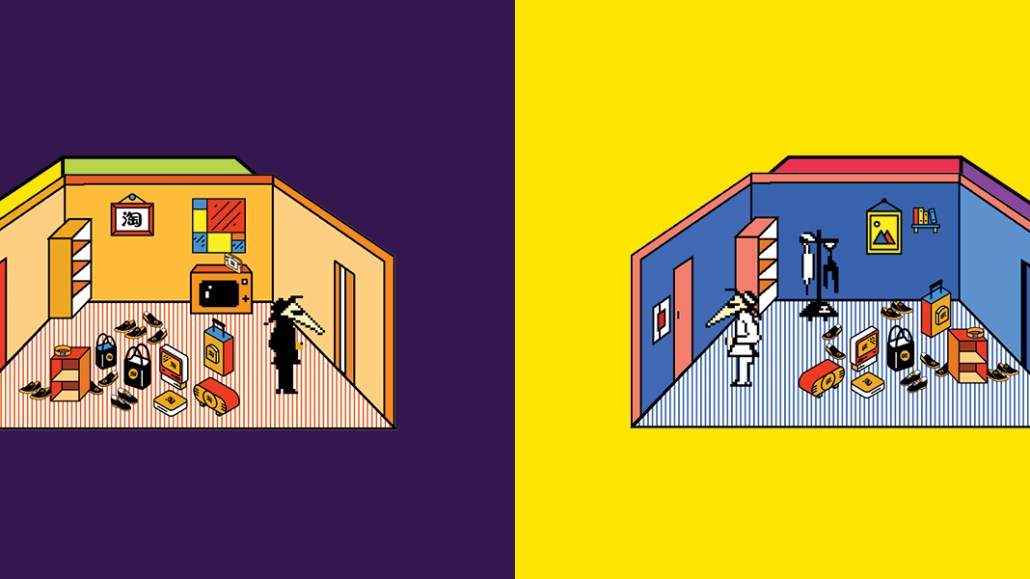

Alibaba says it has employed big data and proprietary technology and works with law enforcement to minimize fakes on its e-commerce platforms. Taobao, which is often compared to Amazon, still has a big reputation for selling knockoffs, which threatens its image with Chinese shoppers as well as its plans to expand into other markets. For the second year in a row, the United States has put the site on a blacklist for sales of counterfeit goods and IP rights violations.

Hankerson says the images of the plagiarized designs he discovered are stored on Alibaba’s cloud content delivery network, and many of them are tied to product listings on Alibaba’s platforms, especially Taobao. For instance, an industrial console with three drawers from Vintage Industrial that costs at least $5,795 can be found on Taobao for as little as $93, and a $12,595 crank table base from Vintage Industrial is listed at less than $50 on Alibaba.com.

Hankerson’s experience resembles that of some well-known brands on Taobao. A quick search on the platform surfaces a fake Gucci men’s belt for around $45 and a $31 tracksuit with a logo similar to Adidas’.

An Alibaba spokesperson says the company has enacted “rigorous measures to ensure that the merchants on its platforms meet the highest standards of integrity.” Alibaba uses big data to scan all new and existing Taobao accounts to prevent the setup of new accounts where the prospective merchants use fake IDs. Alibaba also uses identification techniques like facial recognition to ensure that people seeking to open a store are who they say they are. Using its proprietary technology, Alibaba has found and banned “hundreds of thousands of merchants” for selling IP-infringing products on its platforms, the company spokesperson says.

In January, Alibaba hosted a meeting in Guangzhou, China, with members in its anti-counterfeiting alliance, including Burberry, to tighten IP rights protection through law enforcement, test buying of products and Alibaba’s own online IP protection platform.

During a fireside chat with Charlie Rose at Alibaba’s Gateway conference in Detroit last year, company chief Jack Ma described counterfeiting, IP infringement and cheating as a “cancer” for his business. “There were a lot [of fakes] at the beginning, but you need to fix it,” Ma said onstage. “Today, more than 100,000 brands partner with us. We are the leader in anti-counterfeit and IP protection.”

Still, Alibaba landed on the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative’s 2017 list of “notorious markets” for the second year in a row. “A high volume of infringing products reportedly continues to be offered for sale and sold on Taobao.com, and stakeholders continue to report challenges and burdens associated with IP enforcement on the platform,” states the USTR report released in January of 2018.

Trade group American Apparel & Footwear Association addressed the USTR’s decision in a statement: “Many of our members have reported improvements on Alibaba platforms especially those related to procedures and timelines for takedowns. … At the same time, others have reported ongoing problems on Alibaba platforms, particularly Taobao.” AAFA declined to further comment on the decision.

Michael Zakkour, vp of China practice for Tompkins International, a supply chain and distribution consulting firm, thinks the USTR is biased because counterfeiting is not specific to Taobao, and Alibaba made a big effort over the past year to ensure it wouldn’t show up on the “notorious markets” list.

“There are fakes on Rakuten in Japan, Amazon in the U.S. and Europe and eBay in the U.S., so how can Taobao be the only e-commerce platform on the USTR’s ‘notorious markets’ list?” says Zakkour. “Nobody offers stats to prove that counterfeiting on Taobao is more rampant than other e-commerce platforms.”

Taobao’s business model, which largely consists of third-party sellers, might be partially at the root of the counterfeit issue. With its business-to-consumer platform Tmall, Alibaba charges a brand to open a store, takes a commission on each product sold and makes money through advertising. On Taobao, advertising is the main revenue stream. That means Tmall merchants are typically first-party sellers and rights owners themselves, so they understand IP protection well, while Taobao is filled with third-party sellers who know less about IP protection.

“Fakes don’t exist on Tmall, and counterfeit on Taobao is getting better,” says Zakkour. “There is external and internal pressure for Alibaba to tighten IP protection. If consumers can’t trust the merchandising on its platforms, they will move elsewhere. And Alibaba’s motivation is not to risk the company’s global reputation for selling a few knockoff handbags. It would be silly otherwise.”

But Hankerson’s experience says otherwise. On Feb. 2, he found another 5,000 listings and photos of his company’s products circulating on Alibaba’s cloud content delivery network, and he is now eyeing legal action. “Alibaba has deep pockets. The company should have the technology to block counterfeit listings, and it is liable for damages,” says Hankerson. “My photos are copyrighted with the [U.S.] government, and I told Alibaba repeatedly to take them down, but it’s like falling into a rabbit hole. I want to go after those guys to stop this practice. It’s not fair and shouldn’t be allowed.”

More in Marketing

Thrive Market’s Amina Pasha believes brands that focus on trust will win in an AI-first world

Amina Pasha, CMO at Thrive Market, believes building trust can help brands differentiate themselves.

Despite flight to fame, celeb talent isn’t as sure a bet as CMOs think

Brands are leaning more heavily on celebrity talent in advertising. Marketers see guaranteed wins in working with big names, but there are hidden risks.

With AI backlash building, marketers reconsider their approach

With AI hype giving way to skepticism, advertisers are reassessing how the technology fits into their workflows and brand positioning.