Secure your place at the Digiday Publishing Summit in Vail, March 23-25

‘The data hasn’t gone away’: How Facebook opened Pandora’s box of user data and has struggled to shut it

Years ago, Facebook made it possible for companies like Cambridge Analytica to access information like users’ full names, birthdays, religious affiliations, political views and work histories, whether a Facebook user had directly consented to share it with an outside company or not.

It’s unclear how many of those categories are included in Cambridge Analytica’s ill-gotten trove of Facebook user data on more than 50 million people. Facebook did not respond to a request for comment before press time.

But based on documents detailing the tools Facebook provided to developers that were used to collect the data that Cambridge Analytica received, it’s clear how easy it would have been for a company to collect such personal information through Facebook. And even as Facebook looked to lock down outside access to users’ information, the data it had previously made available likely still exists and has become even more valuable.

“There are people still sitting on most of this data,” said Jonathan Albright, research director at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism. “The data hasn’t gone away.”

How apps gained access to Facebook’s user data

In April 2010, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg unveiled Facebook’s Graph API, a tool for developers to receive data from Facebook to incorporate into their own apps and sites. For example, Pandora could ask people to sign in using their Facebook accounts in order to receive music recommendations based on their friends’ musical interests. But in opening up its user data to the likes of Pandora, Facebook was opening a Pandora’s box of people’s personally identifiable information.

For roughly five years, anyone with a little coding know-how could operate an app or site to collect data from people’s Facebook profiles and their friends’ profiles. So long as a person signed in to the app or site with their Facebook account, that app or site would receive personal information by default, including that person’s full name and gender, plus the full name and gender of each of their Facebook friends. The app or site could also ask for information like the person’s email address and relationship details as well as their friends’ birthdays and political views. Only if a person agreed to provide access to that information would they be able to log in and use the app or site.

This is akin to someone showing their driver’s license to get into a bar and that bar receiving a list of names and genders for every one of that person’s friends. The bar could ask for more information, like when each friend was born, where they work, their political views and their hometown. A person could decline to share that information, but then they wouldn’t be allowed in the bar.

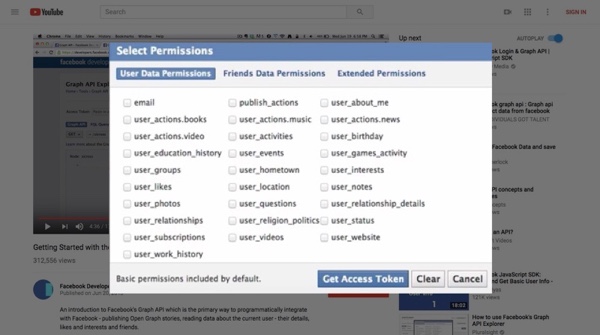

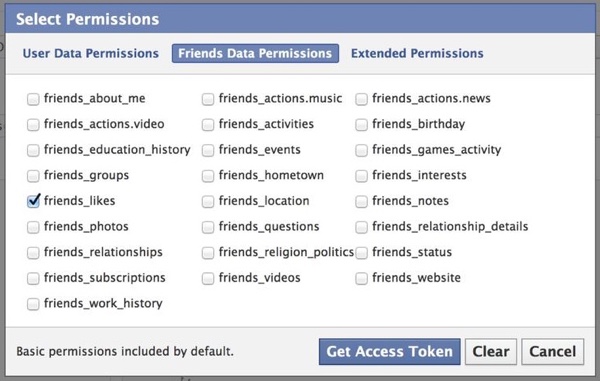

The data Facebook made available

The below images list all the Facebook information, beyond public profile information like name and gender, that a developer could request from the person signing into their account. The first image is from a video uploaded to the Facebook Developers channel on YouTube in June 2013. The second image is from a book published by O’Reilly Media in October 2013 titled “Mining the Social Web: Data Mining Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, Google+, Github, and More.”

In many ways, the data that Facebook allowed developers to access is not so different from the data that companies like credit-reporting firms collect and make available for ad targeting. Experian’s marketing division, for example, provides brands with audience segments that group people by political views, age range and education level. But a major difference is the data from those companies is aggregated and anonymized before brands can access it; the data that Facebook made available through its Graph API was not.

“Having direct individual-level [personally identifiable information] is unlike anything we’d even want access to within the agency,” said one agency executive.

By June 2013, Facebook had made it so simple for outsiders to get information about people’s friends that a limitation it cited was that developers could only get information about a person’s friends but not those friends’ friends.

“The amount of data we can access about the current user’s friends is very limited. For example, we can’t get the friends of these friends,” said Facebook product manager Simon Cross in the video uploaded to the company’s YouTube channel for developers in June 2013. The video demonstrates exactly how developers could use Facebook’s Graph API to pull information from the Facebook profiles of not only the person who signed into the developer’s app or site using their Facebook account but also that person’s friends.

Less than a year after that video was uploaded — and three years after settling with the Federal Trade Commission over a failure to protect users’ privacy — Facebook decided to limit the amount of data that could be accessed about a user’s friends. Starting April 30, 2015, Facebook no longer allowed developers to receive the list of a person’s friends by default when that person signed into their site or app using Facebook. If the person agreed to give the app or site permission to access their friends list, the app would only be able to collect public profile information, like a friend’s name and gender.

Data in the wild

By that time, it was too late. The data was already out in the world, and Facebook relied largely on an honor system for developers to abide by its policy against sharing the data they had collected with others who had not been given permission to access it. That honor system has holes, as the Cambridge Analytica scandal proves. As reported by The Intercept, The Guardian and The New York Times, a researcher named Aleksandr Kogan used the original, leaky version of Facebook’s Graph API to collect Facebook information from people and their friends and then was paid to share that data with Cambridge Analytica, which used it for President Donald Trump’s 2016 election campaign.

As alarming as the ease with which companies could access this data is the data’s lasting value, which continues to this day.

Since the data was not anonymized and could include a person’s full name, birthday and gender, the data can still be used to target people with ads on Facebook. Facebook’s Custom Audiences tool allows advertisers to aim their ads at people based on information, including their first and last names, dates and years of birth and gender. Those identifiers can be used in combination, so that anyone with access to people’s names, birthdays and genders accessed through Facebook’s Graph API can still use that data to target them with ads using Custom Audiences as well as people similar to them using Facebook’s Lookalike Audiences.

Another issue is the fact that the data included people’s actual Facebook user IDs, which are Facebook’s version of a Social Security number. While Facebook disabled the option to use these IDs for Custom Audience targeting in 2014, they can still aid in this targeting. For example, if someone has only a list of actual Facebook user IDs, they can use Facebook’s Graph API to fetch the full names of each user associated with those IDs and then use those names for Custom Audience and Lookalike Audience targeting. And for a time, they could have even used this data to acquire people’s phone numbers.

For nearly two years, advertisers could use a Facebook-provided tool to compare how different lists of people’s information, such as their email addresses or phone numbers, overlapped and determine the phone numbers of people who had not previously provided them to an advertiser, according to a Wired report published in January. Facebook fixed the issue in December 2017 and said it hadn’t found anyone using it to extract people’s information. But for a time, the company also wasn’t aware how Cambridge Analytica accessed its data, and Facebook has not yet been able to ascertain how much of that data Cambridge Analytica still holds.

Data wrangling

Facebook is beginning to address this legacy data issue. The company announced March 21 that it plans to scrutinize apps that had accessed large amounts of user data before the Graph API change that was announced in 2014, audit those suspected of misusing that information and ban the ones that misused it. Facebook will also notify people whose information had been collected and misused by apps such as the one at the center of the Cambridge Analytica controversy, disable data access for apps that a person hasn’t used within the last three months and only allow apps to request people’s full names, profile photos and email addresses when they log in using their Facebook accounts unless the apps submit to a review and are approved by Facebook to request more information.

However, turning off access to this data is not the same as undoing that access. For example, the data that Kogan’s app had acquired was handed off to Cambridge Analytica. Facebook’s audits may be able to trace these exchanges. But they may not.

Facebook could disarm this data, to an extent, by disposing of the Facebook user IDs that outside apps have collected. It could refresh all of its user IDs, or at least those of people whose information was collected and misused. And, as people review the apps that accessed their information, Facebook could give individuals the option to request their Facebook user IDs to be reset, even if none of those apps are found to have misused their data. A Facebook spokesperson did not address by press time whether the company will enable these user ID resets.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Facebook’s actual user IDs could be used for Custom Audiences and Lookalike Audiences targeting. Facebook disabled that option in 2014.

More in Marketing

‘Nobody’s asking the question’: WPP’s biggest restructure in years means nothing until CMOs say it does

WPP declared itself transformed. CMOs will decide if that’s true.

Why a Gen Alpha–focused skin-care brand is giving equity to teen creators

Brands are looking for new ways to build relationships that last, and go deeper than a hashtag-sponsored post.

Pitch deck: How ChatGPT ads are being sold to Criteo advertisers

OpenAI has the ad inventory. Criteo has relationships with advertisers. Here’s how they’re using them.