This story is part of Endgames, a Digiday Media editorial package focused on what’s next, what’s coming, and what’s being phased out in the industries we cover. Access the rest of our Endgames coverage here; to read Glossy’s Engames coverage, click here; Modern Retail’s coverage is available here.

In 2019, West Coast retailer Fred Segal hosted 75 different parties and events at its flagship store in Los Angeles.

Allison Samek, Fred Segal’s president, said the company’s namesake founder had intended for the flagship L.A. store to be a “daytime nightclub” at the core of the business, so events like film festivals and Friday happy hours made sense.

But by March of 2020, as the spread of coronavirus ushered in a pandemic, the 59-year-old retailer began thinking more about convenience. Samek accelerated the company’s digital growth plans, resulting in a revamped website featuring hundreds of additional products and expedited shipping options, including through Postmates. It also launched curbside pickup and an online concierge service, as well as a weekly virtual shopping event called Fred Segal Live. As a result, its site e-commerce has seen 200% sales growth year-over-year.

“Pre-Covid, it was hard not to have a great time in our stores; our customers, employees and the environment simply ‘vibe,’” said Samek. “Covid changed much of what we can do.”

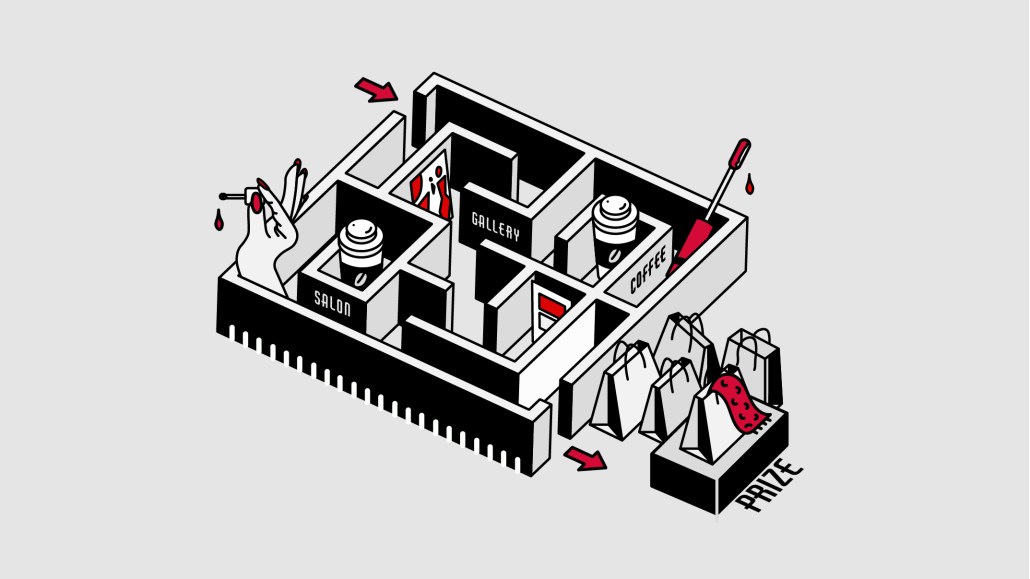

2020 was a tough year for U.S.-based concept stores. In April, less than two years after opening, New York’s 10 Corso Como store closed its doors. In addition to a restaurant and cafe, it featured an art gallery and bookshop. Founder Carla Sozzani, whose original, Milan-based location has been open for nearly 30 years, described the store as a “bazaar.“

Three months later, Neiman Marcus announced plans to close its store in NYC’s Hudson Yards shopping center, which opened in March 2019. Touted by the company as “retail theater,” the store featured a beauty salon and spa, a pop-up florist, three restaurants, and a kitchen offering cooking demonstrations, tastings and mixology classes.

Also in July, Brooklyn-based Kinfolk announced in an Instagram post that it was permanently closing. The store-cafe-nightclub, which was in business for 12 years, was described by the New York Times in 2014 as a “cultural hub.”

It’s not hard to see why the spread of a not-yet-curable disease would make the store-as-cultural-hub less appealing. But with fashion shoppers looking to their phones for inspiration and discovery, stores are now upping their game in other ways, focusing instead on ways they can deepen the relationships they have with their customers.

“If you’re going to leave your house and you’re going to go to a store, it’s about your experience, the customer service and being treated like a queen,” said Stacy Igel, founder and creative director of contemporary streetwear brand Boy Meets Girl, agreed. Since 2001, she’s sold her brand in retailers from Colette to Macy’s.

Igel said the Colette model of offering constant newness is what shoppers want in a physical shopping experience, but moving forward, they’re going to get it from pop-ups rather than look for it in permanent stores.

Elyse Walker, who opened her first multi-brand store in L.A.’s Pacific Palisades neighborhood in 1999, has remained laser-focused on her fashion offering, including maintaining a distinct point of view in the assortment — sexy, edgy, confident — and providing hands-on styling services to customers. She considered making room for a cafe in the company’s Newport Beach store, but decided it wasn’t worth the investment.

“If the store model is confusing to the client, they’re not going to take to it,” she said.

As Walker sees it, the ultra-personal service her company offers is what keeps customers coming back to its stores — a third store will open in Calabasas, Calf. in spring 2021. She and her team communicate with customers via FaceTime “meet-greets” and text messages, and offer a range of styling services including setting up a rack of outfit options in clients’ homes. Currently, 50-70% of the company’s sales are driven through its styling programs.

“I still believe in spending time with one person — and selling one person 10 items, versus 10 people one item,” said Walker, noting that doing so positioned her well for 2020. “When you’re shopping at home and can’t touch and feel the product, you really need to trust the person on the other end of the line.”

Courtney Hawkins, head of retail at The RealReal, said the luxury resale company’s new focus is small-format “core” stores of 2,000-3,000 square feet that will cater to sellers. The first version opened in Palo Alto in December, and a total of 10 will open “in the coming quarters,” in communities with a high density of existing sellers. Each will be equipped with the equivalent staff and services of flagships, including valuation managers and gemologists.

From 2017-2020, the company opened five large flagships in large cities including NYC, L.A. and Chicago, the latter of which is 12,000 square feet. Each is equipped with a cafe, selling locally sourced, sustainable products to reflect the company’s values.

Overall, The RealReal is “pivoting” to offer more convenience, Hawkins said. She noted that it launched buy-online, pick-up in-store; curbside pickup and curbside drop off, for sellers, at its stores earlier this year.

“The more we’re looking at stores, the more we’re looking at how they help with the online business,” she said. “We want customers to know they can get in and out, if they don’t have time. But if they want to spend a lot of time, we want them to know that’s available, too.”

More in Marketing

Zero-click search is changing how small brands show up online — and spend

To appease the AI powers that be, brands are prioritizing things like blogs, brand content and landing pages.

More creators, less money: Creator economy expansion leaves mid-tier creators behind

As brands get pickier and budgets tighten, mid-tier creators are finding fewer deals in the booming influencer economy.

‘Still not a top tier ad platform’: Advertisers on Linda Yaccarino’s departure as CEO of X

Linda Yaccarino — the CEO who was never really in charge.