Secure your place at the Digiday Publishing Summit in Vail, March 23-25

Why forecasting is so hard, from Hurricane Joaquin to the Kardashians’ e-commerce play

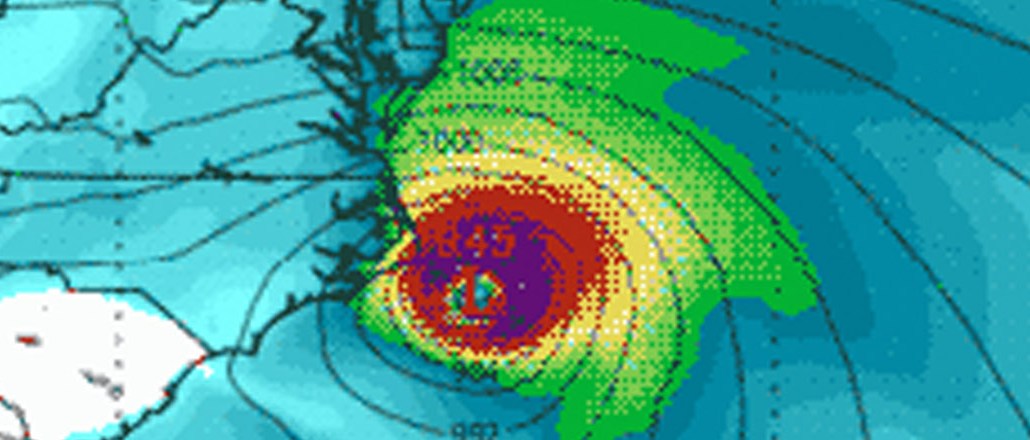

After nearly a week of vital watches and warnings from The National Hurricane Center, Hurricane Joaquin tapped out early, leaving the Southeast battered, but the Northeast with a sunny Sunday. Online, though, another storm is brewing: Kardashian Beauty, the reality royalty’s cosmetics line, is gearing up to launch its own e-commerce platform, marking the first time the products will be sold directly to consumers.

“We’re in a world of hypothesis and assumption,” said Erin Dwyer, svp of global e-commerce and social at Haven Beauty, which manages the brand’s marketing. “All of this is going to launch, and we could be close to the money, or we could be really off.” Like the NHC, Dwyer will have to identify behavioral patters and predict the future, tracing her consumer’s experience from awareness all the way down to sale. But understanding complex customer journeys and predicting outcomes is far from easy.

To understand why predicting a force of nature (be it a Category 4 storm or a Kardashian commerce play) is so tough, we asked James Franklin, branch chief of the NHC’s hurricane specialist unit, how he reads the data, why it’s still not a perfect science, and more.

Crystal ball or time machine?

Hurricane forecasters design their models to predict two main things: the track or path a storm cuts across the map and its intensity at various junctures in time and space.

As Franklin describes it, tracking a storm is fairly simple: “The features that push [a storm] around are usually pretty big and easy to measure.” But intensity’s different. The physical forces that whip a storm into a frenzy actually take place on a smaller scale. That’s where statistical data comes in.

“You look at 15 or 20 years of past data of hurricane behaviors,” said Franklin. “You see which factors are correlated [to a storm’s intensity] and which ones aren’t.”

Marketers, on the other hand, start in reverse: In the case of attribution, they already know whether or not a purchase or other type of conversion or brand engagement activity has been made. It’s their task to determine how heavily each marketing factor impacted that decision. Only then can those models be used for any form of prediction.

The missing link: Good data, right analysis

Hurricane forecasters do share marketers’ frustration: “A big part of the limitation and the reason that forecasts go awry has to do with our ability to measure,” said Franklin. “We just can’t measure the environment with sufficient accuracy and detail to get the models off to a good start.”

Nobody needs to remind marketers, whose key indicators can be downright ephemeral. “You could be out trying someone’s makeup, love it, go buy it online, and we’d have no idea what influenced it,” said Dwyer. “For all we know, a cover of Vogue could have hit with one of the sisters on the cover.”

Even when the key factors are known, there’s another level of complexity. “It’s A + B + C = sale,” said Dwyer, “and maybe B has much more influence, but C reminded them and made [the sale] happen sooner than expected. One of the biggest frustrations is the timing. It’s not always a linear path.” This makes attribution analysis and interpretation essential.

The human factor

So, on the surface, predicting whether a consumer will make a purchase or how they’ll respond to an ad follows the same logic: Identify the important factors, collect enough data, then run the models. But as soon as you break that surface, the differences are glaring.

“Prediction in physical systems is subject to physical laws that govern the way objects behave,” said Franklin. That’s not the case when you’re predicting human behavior.

“There’s an entire interconnected ecosystem that we have to consider,“ said Dwyer. “Humans are not simple, and we can’t think that they’re going to fall into line.” And unlike hurricane forecasters, marketers don’t have 15 to 20 years of consistent data to work from. But if the nut is cracked, Dwyer is hopeful about the predictive potential.

“If social’s a heavy element [in the attribution model], it tells you something very different than if it’s email and search,” she said. “One’s very editorial, one’s very transactional. [The model] could tell you how to shift your whole marketing plan based on how your consumers experience your content.” This payoff only happens when attribution takes into account the relative worth of each channel, campaign and tactic.

More from Digiday

Best Buy wants to be the hub for AI-powered hardware like glasses, laptops

The tech retailer is looking for growth, as its revenue was essentially flat this past fiscal year from the year before, at almost $42 billion.

Future of TV Briefing: OpenX adds attention targeting for CTV ads backed by TVision

This week’s Future of TV Briefing looks at a new ad targeting option for CTV advertisers wary of people staring at their phones while an ad airs.

AI surfacing is messy: Data shows publisher visibility and traffic often misalign

Reports tracking publishers in AI chatbots abound but conflicting rankings and uneven referral traffic reveal the murkiness of AI visibility.