In times of belt-tightening, the Financial Times is making more data-informed decisions around audience development. For this reason, it is improving its approach to comments and commenters on site.

With a lot of conversation having migrated to social media, it’s not uncommon for some publishers — like The Telegraph, for example — to ax its comments section entirely. But the FT believes its readers are paying to be part of this community and to take part in the debate.

Up until recently, the strategy around comments was more about damage control. Last year, Renée Kaplan joined as head of audience engagement and has built up an 11-person team. Now that team is getting more proactive and is using comments as a tool for engagement. “For other media companies, the comment strategy is more about growth,” said Kaplan. “For the FT, we have a unique commitment to make something of these comments, the readers are entitled to being part of the quality conversation and what the community has to offer.”

Currently, FT readers can comment on news stories, analysis and opinion pieces, where the highest volume of comments is. The FT routinely disables comments on more explosive news stories, though — Russian politics, climate change, Islamic extremists — because little productive discourse took place here.

That said, here’s how its strategy is shaping up.

Putting a commercial value on the commenter.

Only subscribers can post comments; therefore, the FT already knows a lot about them. Not enough, though. Leading the research into understanding the commercial value of commenters is community manager Lilah Raptopoulos.

“We want to know whether they are, as we suspect, our most engaged users,” said Raptopoulos. “We need to understand what the commercial correlation is, what effect does a comment have on our subscribers, will commenters share more, or visit the site more often?” Anecdotally, the team has hunches about these hypotheses, but for now, this is a work in progress.

Extending the audience.

Comments have been also a springboard to bring in new, younger audiences, crucial for a heritage brand like the FT wanting to stay relevant.

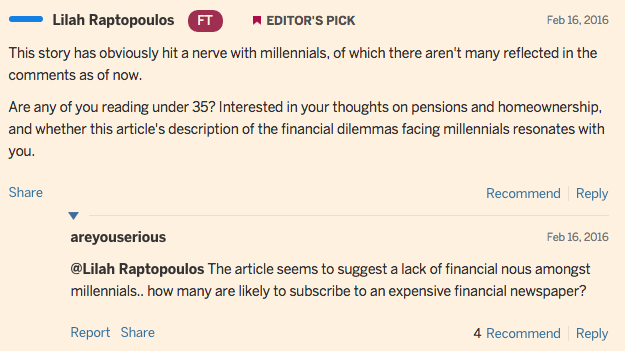

The comments on a recent story called “Why millennials go on holiday instead of saving for a pension” were overwhelmingly left by older readers and showed a real lack of understanding about young people. So Raptopoulos jumped in calling out for younger voices, and cross-promoted the call-out on social media too.

As a result, the FT received around 15 more comments from younger people. Kaplan thinks it’s unlikely they would have been subscribers; instead, they took the time to sign up to the one-month trial subscription which costs £1 for one month in order to comment. This led to its own piece on the most interesting comments, leading to another 150 comments.

Getting journalists to care.

In a shrinking newsroom, getting reporters to care about comments is a challenge, making it all the more important to have this data-informed research on the value of a commenter.

“Newsrooms tend to hate comments,” admitted Kaplan. “They’re a pain. There are trolls. People feel abused.” Kaplan’s team developed best practices, based on the minority of journalists who are already engaging with commenters. Tips included tricks for turning around a negative tone and for leading the conversation offline.

Shaping article ideas.

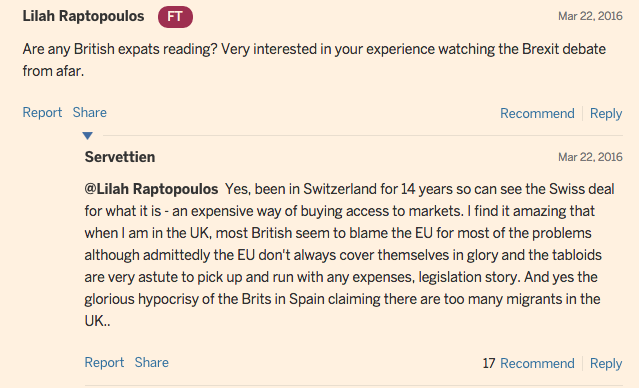

The FT is not typically a publication that goes in for crowdsourcing article ideas, but there are occasions where the personal experience of its readers is proving to be particularly enriching, triggering leads and story ideas.

Rather than hoping for the best from comments, the FT is playing with different formats in the space under articles and seeing which ones work the best for feedback. This private call-out box was placed underneath a news story about how Brexit would impact U.K. expats living in Europe. People could anonymously give feedback on their own experience knowing that their responses would help the journalism. It also went out in newsletters to subscribers interested in Brexit, and under other relevant stories. In 48 hours, the FT received 350 responses from U.K. expats in 45 countries, on their experiences, which are being used to shape an interactive piece for the site.

Trolls are subscribers too.

Just because the FT has a paywall, that doesn’t shield it from trolls. Like other publications, it will delete posts that are defamatory, personal attacks or outright false. Users usually have three strikes before they are shut down. Comments are moderated practically 24 hours a day, and if something is deleted or a warning is sent, Raptopoulos is in there saying why and linking to the guidelines.

But these people are paying for the privilege to engage in debate, so it’s a double-edged sword. “Outright banning is never the right approach,” said Kaplan. “We’re not here to censor.”

“We see the value of comments as fundamentally good,” adds Raptopoulos. “We’re more interested in encouraging better conversation than just chastising the bad.”

More in Media

In Graphic Detail: The scale of the challenge facing publishers, politicians eager to damage Google’s adland dominance

Last year was a blowout ad revenue year for Google, despite challenges from several quarters.

Why Walmart is basically a tech company now

The retail giant joined the Nasdaq exchange, also home to technology companies like Amazon, in December.

The Athletic invests in live blogs, video to insulate sports coverage from AI scraping

As the Super Bowl and Winter Olympics collide, The Athletic is leaning into live blogs and video to keeps fans locked in, and AI bots at bay.