Secure your place at the Digiday Publishing Summit in Vail, March 23-25

With Facebook’s power growing, publishers scramble to connect directly with audiences

After years of guzzling at the platforms’ traffic spigot, publishers’ worst fears are coming true. The platforms have inserted themselves between publishers and their readers, making it harder for publishers to make money off them.

To counter, publishers are getting smarter about striking direct connections with readers, getting people to come to their sites where they have full control over audience data and monetization.

“The benefits accrue to whoever’s closest to the customer,” said Omri Bloch, the chief operating officer of Bounce Exchange. “[For publishers], you have third parties who effectively own the customer relationships. Publishers realize there’s an existential threat there.”

To reduce their dependence on these platforms, publishers are turning to variations on a common strategy: identify segments of their reader base that can be super-served, get them to check out unique content built on their own websites or newsletters, or even offline, and get them to subscribe or build the habit of visiting that content regularly.

“You can do a lot of things to form habits in people,” said Ben French, the vp of NYT Beta, the Times unit that’s been developing niche sections like NYT Cooking, Well and Watching to cater to readers’ interests.

Double-edged sword

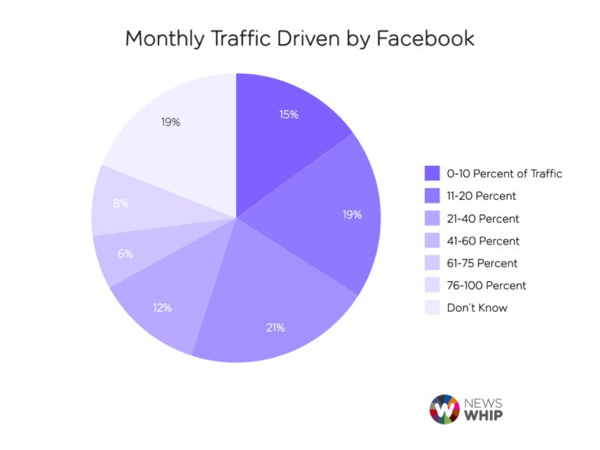

Facebook and Google are vital traffic suppliers for publishers. NewsWhip last month found Facebook alone accounts for 21-40 percent of traffic for one-fifth of all the publishers it surveyed. For another quarter of them, Facebook was responsible for 41-75 percent. Those same publishers deeply depend on Google, the long-reigning king of search, and both companies have been making moves to keep readers on their platforms.

Those moves are having a profound effect on how well publishers can monetize their audiences. Google’s speedy article format, Accelerated Mobile Pages, for example, does not support all ad types. Publishers have begun complaining that the ad revenue they generate from Instant Articles, Facebook’s fast-loading article template, already lower than what they can generate on their own sites, is going down. The Independent, for example, said the ad rates it has gotten for its Instant Articles have fallen by more than 15 percent over the course of this year.

Publishers have complained that while Instant Articles might load faster, they don’t provide anywhere near the kind of audience data that publishers can capture when readers visit their own sites.

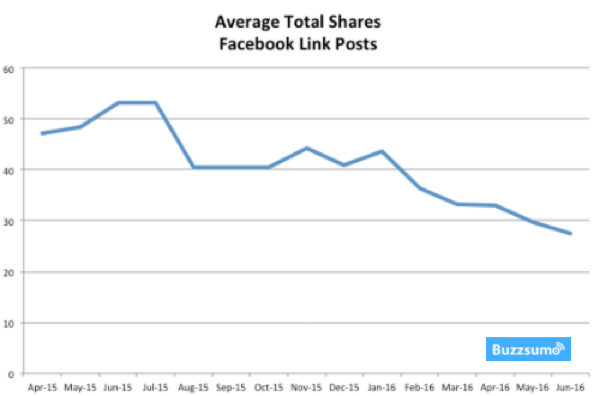

Publishers can eschew these new formats, but they do so at their peril: Social analytics firm BuzzSumo found last spring that the reach of link-based posts, which drive people from Facebook to publishers’ sites, has declined precipitously this year as Facebook has pushed Instant Articles, which members read without leaving Facebook.

Better mousetraps

Even when Facebook and Google were reliable sources of traffic for publishers, it was hard for publishers to get readers to stick around. To combat high bounce rates, publishers have been working to keep readers on their sites longer or capture them in the form of an email subscription or a site registration.

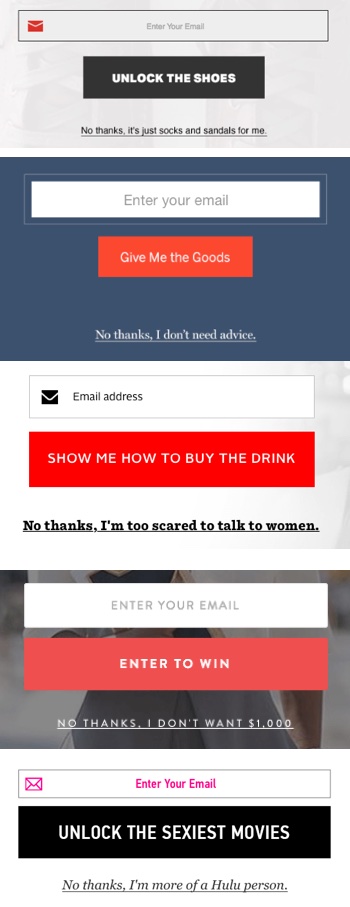

That has led dozens of publishers to a company called Bounce Exchange. The 4-year-old firm, which serves context- and user-specific calls to action to a site’s visitors, got started as a tool for e-commerce companies, but it realized in 2014 that its service could be useful to publishers, too. Today, Bloch said, Bounce Exchange serves “pretty much every major publisher in the U.S.,” with clients ranging from lifestyle publishers like Cosmopolitan and Playboy to vertical publishers like Four Hour Workweek and Fatherly (and, yes, even Digiday). Clients use its tools to drive everything from newsletter signups to subscriptions to purchases. “Those initial, legacy clients have expanded a great deal,” Bloch said.

Once a publisher gets a reader’s email address, however, more work is needed. Because not everybody responds the same way to email blasts, publishers including Fusion and VentureBeat use tools like Iterable to vary the cadence, tone and style of the newsletters, based on how recipients respond. “What you see almost all publishers out there doing is the same,” said David Rangel, Iterable’s vp of marketing.

Welcome mats

Once a reader is on the site, publishers are trying make sure they see content that’s relevant to them. That’s easier for niche publications than general-interest sites. For example, a cooking site can infer, using first- and sometimes third-party data, which of its readers are vegans, or which ones like grilling, and adjust the look and content a visitor sees accordingly.

But for general-interest sites, personalizing a page is harder. How do you decide what to show somebody who has read an article about Brexit, a review of a James Bond movie and recipe for Thai curry? It also creates a tension between catering to visitors and sharing the site’s breadth.

For The Wall Street Journal, the answer has been to shift from a one-size-fits-all subscription model to several different tiers of digital membership, using first- and third-party data to identify and segment its readers quickly. It’s also moving toward a point where every article recommended to site readers is unique to that reader.

For other sites, the answer is to make each section look and feel like a standalone media property. The New York Times’ sites Well, Cooking and Watching, three of the six editorial properties developed by NYT’s Beta team, are all technically part of the Times’ domain, and most are built off content that was originally published on the Times’ website. But each has a distinct look and feel.

“A general-interest publication is really a conglomerate of niche special-interest publications,” said Nick Edwards, co-founder of Boomtrain, a machine intelligence layer for marketers and publishers. “They need to become specialized in each of those areas they cover.”

Play by the rules

Of course, serving small communities on one’s sites and hoping its members bring friends will take you only so far. Publishers still need the platforms they live on now. “Owned and operated is the tip of an iceberg,” said Adam Rich, co-founder of Thrillist Media Group.

In fact, if you build a platform-based audience that’s big enough, you can still learn a lot about it, algorithms be damned. Over the last two years, CBS Interactive’s gamer site GameSpot went from having a minimal Facebook video presence to more than 140 million views per month by focusing on short clips, just the kind favored by Facebook’s algorithm.

GameSpot’s page engagement got so strong that, when GameSpot surveyed viewers on their gaming platform preferences, it got more replies from Facebook than from any other channel, including email and its own site. Those replies gave GameSpot a clearer picture of which consoles its readers used most and types of games they were most interested in, information it immediately brought to its ad partners. “That was a great stake in the ground for us,” said Michael Powers, a senior vice president at CBS Interactive.

Facebook and Google will surely continue to tweak their algorithms and their products over time. But as platforms and publishers both fight harder to hold onto their audiences, the need to make money on each visitor will intensify. “If you’re gonna get less people in the store,” said Mark Zagorski, the executive vp of Nielsen Marketing Cloud, “you better monetize the hell out of them when they get there.”

More in Media

Media Briefing: As AI search grows, a cottage industry of GEO vendors is booming

A wave of new GEO vendors promises improving visibility in AI-generated search, though some question how effective the services really are.

‘Not a big part of the work’: Meta’s LLM bet has yet to touch its core ads business

Meta knows LLMs could transform its ads business. Getting there is another matter.

How creator talent agencies are evolving into multi-platform operators

The legacy agency model is being re-built from the ground up to better serve the maturing creator economy – here’s what that looks like.