Last chance to save on Digiday Publishing Summit passes is February 9

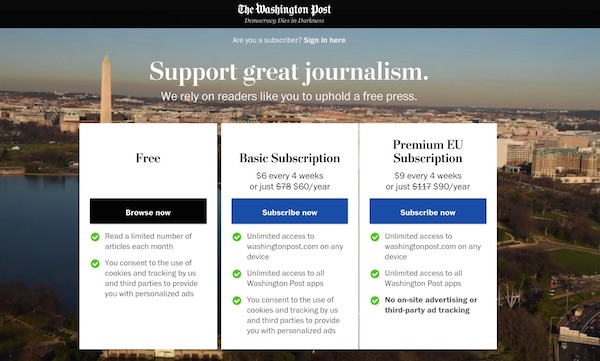

The Washington Post puts a price on data privacy in its GDPR response — and tests requirements

Some U.S. publishers have blocked visitors from the E.U. to their sites rather than comply with the wide-ranging General Data Protection Regulation to protect people’s online privacy. The Washington Post went an extra step and put up a paywall for E.U. visitors, upselling them to a $90 a year “premium EU subscription” in exchange for no ads — and the privilege of not having their data tracked. The premium subscription is $30 more than the cost of a basic online subscription to the Post.

“This is something we’ve been working on for a long time to create transparency, minimize friction for our readers and ensure compliance,” emailed Miki King, vp of marketing at the Post. “Our approach was to give readers an additional option beyond our consent-based offerings of free limited access or a subscription. We’ve now added a third option that offers no third-party tracking or advertising at a premium.”

The Post wouldn’t comment on the legal basis for the offer, but some question the offer’s legality. The GDPR requires businesses to justify collecting people’s online data, by getting their consent or through other means. The question is whether the Post’s offer flies in the face of the law’s requirement that consent be freely given.

Tim Turner, a U.K.-based independent consultant who trains companies in GDPR, said the Post is “forcing consent for the free option and making you pay for the tracking-free option. Forcing those who can’t/won’t pay to accept tracking seems to kill legitimate interests. Either way, I think it’s likely to be a breach.”

IAB Europe last fall published a paper saying that “private companies are allowed to make access to their services conditional upon the consent of data subjects.” Johnny Ryan, formerly head of ecosystem at anti-ad blocking firm PageFair, disagreed, saying the GDPR forbids such “tracking walls.”

“It’s all measuring what does it mean for something to be freely given,” said Gary Kibel, partner in the digital media, technology & privacy practice at the law firm Davis & Gilbert.

Kibel, who represents clients in advertising, publishing and ad tech, wouldn’t offer an opinion on the legality of the Post’s approach, but did point out that a question is whether this approach arises to the level of violating that “freely given.” Employees, for example, can’t be considered to be freely giving consent if their job depends on it. “Is viewing a website equivalent to that?” he said. “Probably not.”

U.S. publishers have reacted to GDPR with various strategies. Some like Tronc have simply chosen to turn away E.U. visitors. Gannett’s USA Today is offering a bare bones version of its site that some are noting as a far better user experience. The New York Times does not appear to be running any programmatic ads. (The Times has not responded to requests to confirm this.) The Post is taking a novel approach in literally putting a price on taking data-tracking out of the media equation.

The issue for ad-supported publishers is that their business model is predicated, to varying extents, on their ability to track and retarget people with ads. The Post tactic is reminiscent of how publishers have pushed back against ad blockers by asking or demanding that they disable the ad blocking software in order to access the site, or giving them the choice to pay for an ad-free experience.

Brian Kane, COO and co-founder of Sourcepoint, which helps publishers monetize ad blockers, predicts publishers will try a variety of options as they figure out how to balance access with monetization. Sourcepoint, for its part, has a consent management platform that lets publishers give users payment options when they are asked for their consent, and Kane said “a lot of publishers” are talking about trying it out. To be GDPR-compliant, he said, the CMP lets people dismiss that option and continue on to the site, though.

The move to cut off E.U. visitors altogether is likely to be a short-term approach, but as Kane and others have pointed out, it has larger consequences.

“There’s a problem with society in that we’re going to go back into our fiefdoms from an information-sharing perspective” he said. “Publishers have to figure out ways to fund their operations. [The CMP] is a way of marrying that strategy with transparency and data use, as long as you can thread the needle in terms of compliance.”

More in Media

Brands invest in creators for reach as celebs fill the Big Game spots

The Super Bowl is no longer just about day-of posts or prime-time commercials, but the expanding creator ecosystem surrounding it.

WTF is the IAB’s AI Accountability for Publishers Act (and what happens next)?

The IAB introduced a draft bill to make AI companies pay for scraping publishers’ content. Here’s how it’ll differ from copyright law, and what comes next.

Media Briefing: A solid Q4 gives publishers breathing room as they build revenue beyond search

Q4 gave publishers a win — but as ad dollars return, AI-driven discovery shifts mean growth in 2026 will hinge on relevance, not reach.