Secure your place at the Digiday Publishing Summit in Vail, March 23-25

‘Trying to let our hair down’: How The New York Times is getting creative with push notifications

In June, The New York Times dropped seven emojis — two taxis, two hot dogs, a pencil, a heart and the Statue of Liberty — in a mobile push notification to promote its magazine’s all-comics issue on city life. Eric Bishop, who oversees push at the Times, said he started out thinking three emojis would be good (and already more than the Times had ever put in a push), but Jake Silverstein, the magazine’s editor, argued for more, saying: “I think we can make this even more fun and delightful.”

The push is a constrained medium, with limits on characters and visuals. But because push is becoming so important as a way to drive traffic to articles, the Times and other publishers are finding new ways to (ahem) push its expressive limits.

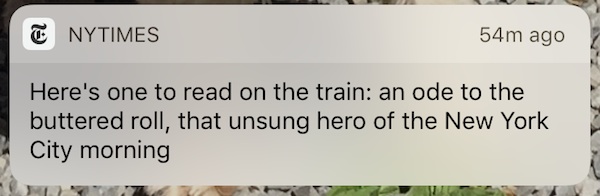

When the Times set up a dedicated push notifications team two years ago, its pushes were basically headlines without much context. Since then, it’s tried to make them more conversational and contextual, keeping in mind the personal nature of the lock screen and knowing people may just want to read the push and not click through.

“We’ve been trying to let our hair down a little — to be more internet-y,” Bishop said.

The Times isn’t alone in trying to make its pushes more conversational. CNN, too, has experimented with this approach, treating the push as appointment reading and pushing out stories that aren’t necessarily breaking but tap into interests people feel strongly about, like parenting.

The Times has a three- to eight-person team on its news desk that handles pushes, among other things. The team sends out around three a day on a typical day, or on really busy days, as many as eight or 10. But it spread the word about why pushes matter, and it’s worked. Individual reporters now lobby for their stories to be pushed; notifications’ wording are labored over in Slack; and even masthead editors get involved.

“It’s a big change for the newsroom to be thinking so much about push,” Bishop said. “I’m getting emails from reporters. That never happened before. And certain editors are pushing notifications all the time.”

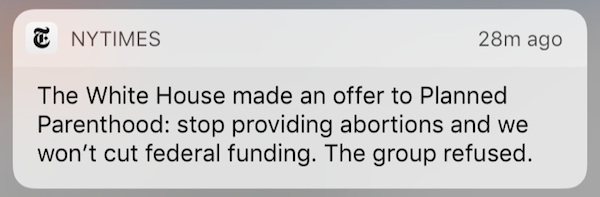

Increasingly, the notifications are being written collaboratively or by the reporters themselves, especially when the story in question is a sensitive one. Political reporter Nicholas Confessore has emerged as an in-house expert. His “Special Report: The wealthiest American families have built a private tax system for the rich. Here’s how it works.” push was a top performer for the Times.

Like so many aspects of distributing news, publishers still are at the mercy of platforms when it comes to pushes. On Apple News, for example, where publishers can turn on notifications, some stories don’t render well, so the Times may not push those. Apple and Android have different push systems and features (Android devices display fewer words than Apple devices, for example), so publishers have to write pushes with both platforms in mind.

Still, at a time when publishers’ traffic is increasingly coming through social side doors, the pushes still are an important way to get people to publishers’ own mobile apps, where they control the experience and monetization. A good push will drive three or four times as many swipe-throughs to the Times’ app.

“Any time we push anything, you see a big spike in readership on a story,” Bishop said. “And it’s not uncommon for half of the traffic in the app to come from the push.”

More in Media

How medical creator Nick Norwitz grew his Substack paid subscribers from 900 to 5,200 within 8 months

Creator Playbook: Unpacking the strategy behind medical YouTuber Nick Norwitz turning to Substack to significantly grow his brand.

Media Briefing: In the AI era, subscribers are the real prize — and the Telegraph proves it

In an era where AI is eroding referral traffic and third-party distribution, a subscriber who pays directly has become the most valuable reader a publisher can own. Springer just bought over a million of them.

Layoffs hit LADbible Group’s social video team amid slower user-generated content growth

Social-first publisher LADbible is in the middle of a second round of layoffs to its social video team, having suffered massive drop-off in Facebook video engagement.