Secure your place at the Digiday Media Buying Summit in Nashville, March 2-4

‘The inevitable maturation of the industry’: Desktop ad blocking is past its peak

Through the middle of the last decade, desktop ad blocker usage soared as adoption of the software moved beyond techies and gamers and into the mainstream. But signs suggest that meteoric rise is well past its peak.

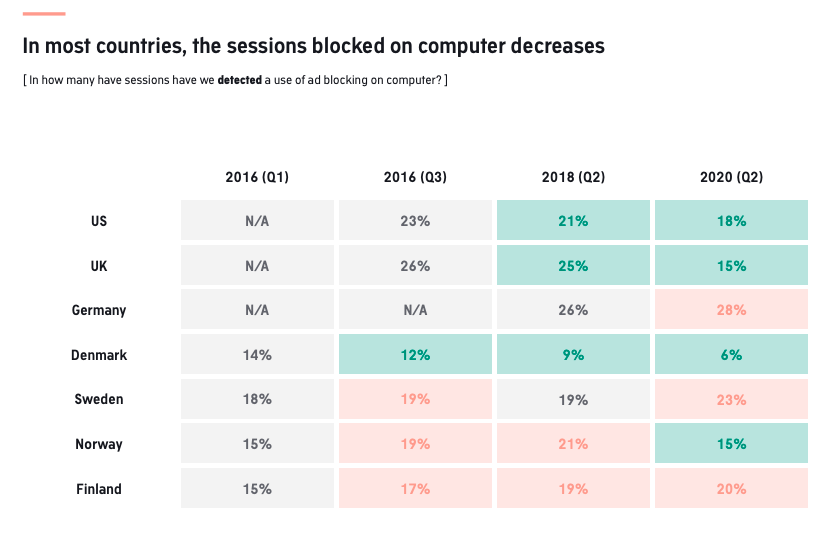

An online survey of more than 14,000 participants in the U.S., U.K., Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Norway and Finland conducted by martech company AudienceProject found fewer respondents said they used ad blockers in 2020 than four years ago.

In the U.S., for instance, 41% of respondents said they used an ad blocker in the latest round of the survey — conducted between April and June 2020 — versus 52% in 2016. (However, the 2020 number was slightly higher than the 39% of those surveyed who said they used an ad blocker in 2016.) In the U.K., the number of people saying they use ad blockers has steadily declined: 47% in 2016; 41% in 2018.

AudienceProject also attached an ad to the online survey and used its measurement technology to detect whether the respondents were actually using blocking software at that moment. In most countries, the sessions blocked on a computer decreased in 2016 and 2018 versus 2020 — though there were slight increases recorded in Germany, Sweden and Finland.

Data from consumer insight company GlobalWebIndex’s latest quarterly survey of more than 100,000 global participants on average also found those saying they used an ad blocker had declined: To 42% in the second quarter of 2020, down from 49% in the year-ago quarter, 46% in 2018 and 48% in 2017.

There are a few intertwining theories as to why fewer people are using ad blockers on their desktops — ranging from the shift to browsing on mobile devices, to publishers and tech companies asserting more discipline around the display of annoying ads like pop-ups and autoplay videos with sound on.

Ben Williams, director of advocacy at Adblock Plus owner Eyeo, acknowledged via email that ad blocking on desktop computers has dropped off since the “halcyon days in the summer of ’16” primarily, he said, because fewer people are browsing on desktop computers.

While desktop ad blocking has declined, mobile ad blocking rose globally by 64% between 2016 and 2019 to 527 million users, according to a separate report released in February from Blockthrough, a company that helps publishers recover revenue lost to ad blocking. That growth was mainly driven by users in Asia and India — particularly through adoption of the UC mobile browser, which was estimated to have more than 400 million monthly active users at the end of 2019.

Mobile ad blocker user growth hasn’t yet been as profound in the U.S. and European markets. AudienceProject’s research found just 7% of respondents in the U.S. were detected to be blocking ads on mobile devices in 2020, up from 5% in 2018.

Much has changed in the ad industry since Williams‘ “halcyon days” of blocking in the middle of the last decade. Legislation such as the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation and the California Consumer Privacy Act have forced publishers to be more upfront about the data they collect for advertising purposes and the value users receive in return. (Some publishers even moved to prevent ad blocker users from viewing their content.) And as ad blocking grew in popularity, the digital advertising industry was forced to be more introspective about the types of ads that annoy users.

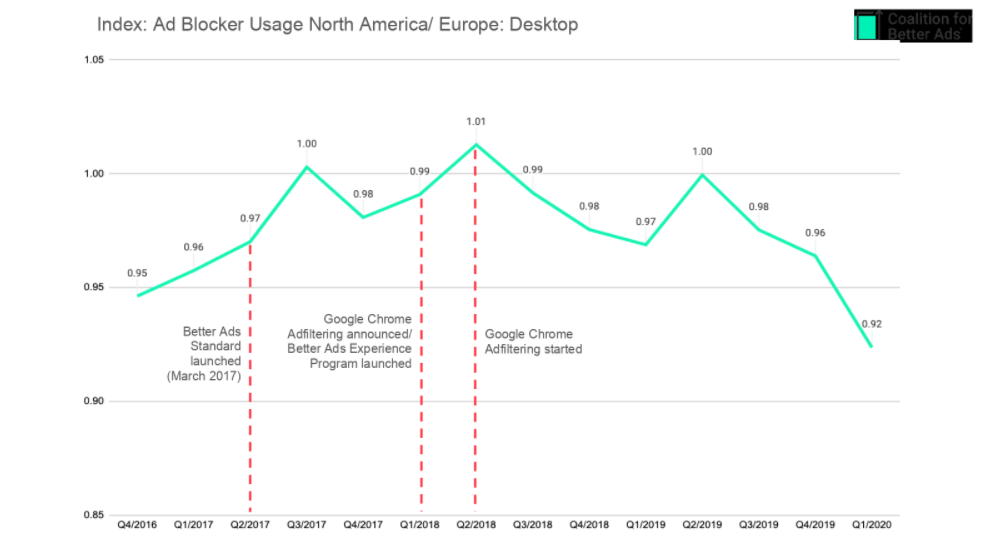

In 2016, a group of companies and trade bodies including Google, GroupM, Procter & Gamble, the Interactive Advertising Bureau and the World Federation of Advertisers formed the Coalition for Better Ads. Overseen by law firm Venable, the cross-industry group identified over a dozen intrusive ad formats that the industry should seek to avoid. In 2018, Google’s Chrome introduced a filter to automatically block out ads that don’t meet the Coalition’s ad standards.

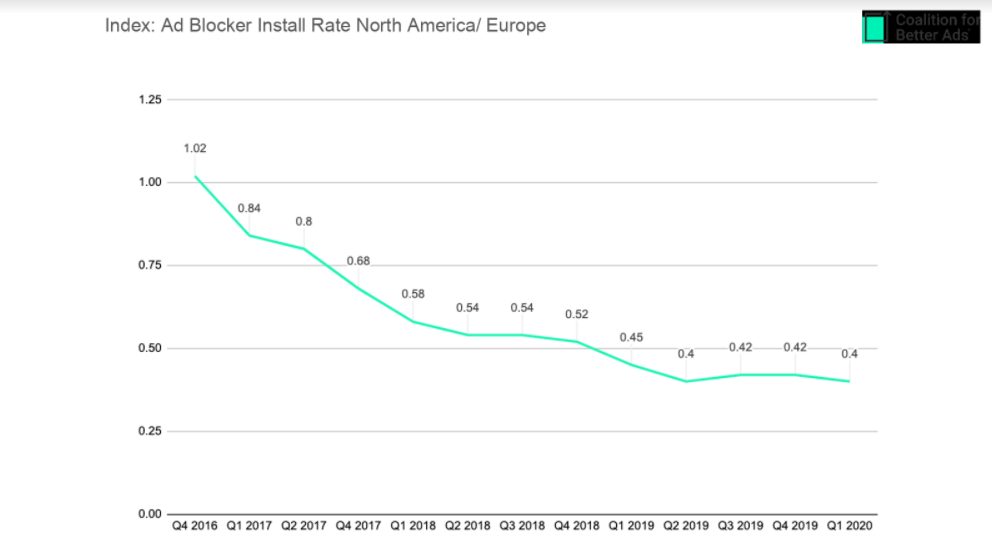

Neal Thurman, director of the Coalition for Better Ads, said the ad blocker install rate on desktop Chrome in North America and Europe has dropped 60% since discussions about forming the group began in late 2016 and the first quarter of 2020.

While not wanting to take the all the credit, Thurman said: “Our standards have had some impact in cleaning up the worst of the worst experiences that really pushed consumers to stop ad blocking.”

“It’s the inevitable maturation of the [digital ad] industry,” he continued. “We’ve proven ourselves — all the numbers show we’re now bigger than TV and print combined — now it’s time to figure out what eggs we broke getting there.”

In the early days, ad blocking was primarily driven by browser extensions. Now browsers are offering anti-tracking and ad-blocking features as standard. On anti-tracking front, those include Apple Safari with its Intelligent Tracking Prevention feature; Firefox’s Enhanced Tracking Protection; and Microsoft Edge’s Enhanced Tracker Prevention. Elsewhere, mobile browsers including UC Browser, Brave, Opera Mini and Adblock Browser block ads by default.

“We have seen a diversification in the types of ad blocking,” said Blockthrough CEO Marty Krátký-Katz. For example, its previous research methodology for observing ad blocker use — inferred by the number of downloads from the open source EasyList blocklist — doesn’t capture the Firefox browser’s blocker when users choose the “strict” setting, which uses the Disconnect.me blocklists. In general, “there’s more dark matter,” especially as some ad blocking software is designed to go undetected, Krátký-Katz said.

At the same time, the AudienceProject survey suggests users’ attitude toward ads might be changing. To be sure, around half of the respondents it surveyed had a negative view towards ads on websites. But in countries like the U.K., fewer respondents had a negative attitude towards those ads in 2020 (54%) than in 2018 (57%). However, in the U.S., more respondents had a negative view this time around (47%) compared with 2018 (42%).

“Ad blocking has evolved into ad filtering in that same period: Today, most ad-blocking products allow ads to pass if they are more respectful of user experience,” said Williams. “This means more ads in more sessions, but fewer annoyed users — even the ‘ad blockers’ — and that’s a good thing.”

More in Media

From feeds to streets: How mega influencer Haley Baylee is diversifying beyond platform algorithms

Kalil is partnering with LinkNYC to take her social media content into the real world and the streets of NYC.

‘A brand trip’: How the creator economy showed up at this year’s Super Bowl

Super Bowl 2026 had more on-the-ground brand activations and creator participation than ever, showcasing how it’s become a massive IRL moment for the creator economy.

Media Briefing: Turning scraped content into paid assets — Amazon and Microsoft build AI marketplaces

Amazon plans an AI content marketplace to join Microsoft’s efforts and pay publishers — but it relies on AI com stop scraping for free.