Secure your place at the Digiday Media Buying Summit in Nashville, March 2-4

From frenemy to friend: How Google won publishers over

In February, Facebook hosted dozens of media company executives at its offices to show its content and product plans. Earlier, it had held roundtable meetings with 100-plus publishers while former TV anchor Campbell Brown, now Facebook’s director of news partnerships, threw soirees at her Manhattan apartment with news and journalism bigwigs.

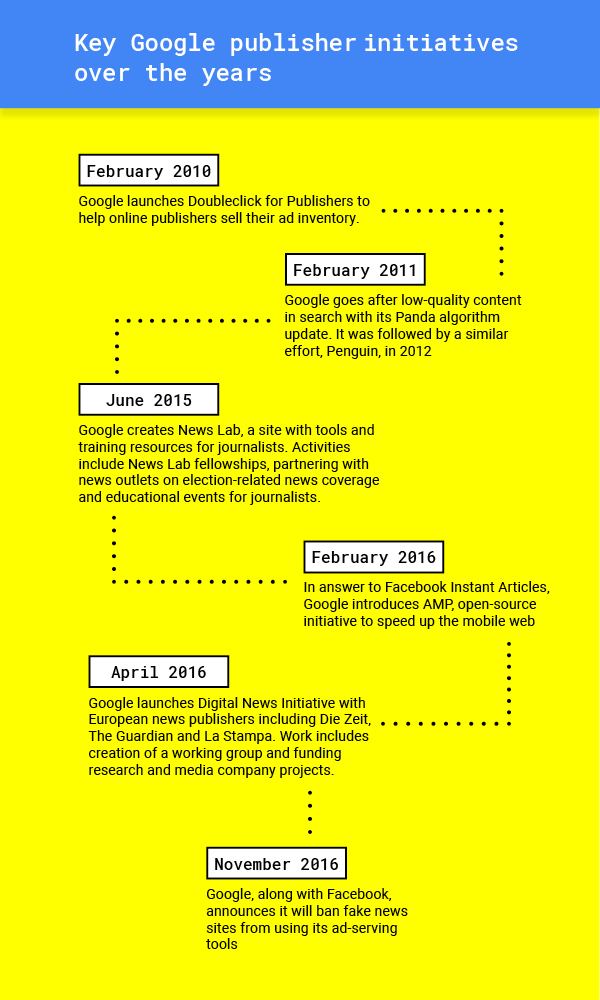

News industry veterans have seen this all before. To them, Facebook is borrowing from the playbook Google has been using for years. Google has long tried to work with publishers, even if not always satisfactorily, on ad monetization and search results. In the past couple of years, its approach has evolved to fund news projects and support industry conferences and events like the secretive annual gathering, Newsgeist.

No one is confusing this with altruism — Google has a business to run — but this approach has helped position it more favorably with publishers than that other platform giant, Facebook. At a time of fear and loathing of platforms, you find a lot more directed at Facebook than Google.

A complementary model

Much of this stems from a simple fact: Google has a different business model than Facebook. Google’s business revolves around search advertising, which means sending users away from Google. Facebook, other other hand, operated a proprietary, closed network that is dependent on keeping people on its site or app in order to show them ads.

What’s more, Google is further down the road of maturity than Facebook. It bought DoubleClick a decade ago. And with DoubleClick came Dart for Publishers, the critical infrastructure used by most publishers in managing their advertising.

“They had DFP and recognized the ability to leverage all the inventory publishers have,” said Michael Kuntz, svp of digital revenue for the USA Today Network. “From day one, they cut the publishers in. I don’t think it was out of the kindness of their hearts, but their interests align more organically with publishers. In the case of Snapchat, Twitter and others, they have a much different agenda that is geared toward launching new products and keeping people on their sites. Hopefully content is a part of that, but I haven’t seen any real evidence that they’re interested in working with publishers in a way for publishers to make meaningful revenue.”

David Besbris, vp of engineering at Google and its AMP project lead, said Google’s interests are “extremely aligned” with publishers. Google needs publisher content to keep people coming to its search engine, and publishers’ inventory drives its display advertising business. Google and publishers also both want to preserve the open web as a counterpoint to Facebook and Snapchat’s walled gardens. “We make money when our partners make money,” he said. “If there’s no information out there because the publishers have gone out of business, that’s bad for us.”

Charm offensive

That’s not to say the relationship has been without its ups and downs. Early on, publishers worried Google was siphoning off traffic by running snippets of their articles in search results. It’s faced a backlash in Europe by publishers and competitors who see the search giant as overly dominant and cavalier with privacy concerns. In its formative days, Google would ding publishers with algorithm changes — fretfully called “Google dances” — and publishers were mostly met with silence when trying to figure out why.

Google has used soft power to woo wary publishers, too. In 2015, Google launched the News Lab, a site with tools and training resources for journalists; and the Digital News Initiative in Europe, including 150 million euros in funding. Last year it introduced Accelerated Mobile Pages, its answer to Facebook Instant Articles, which loads publishers’ mobile article pages lightning fast in the app.

Efforts like these happened because Google was spending more time listening to publishers, Besbris said. Google realized that its size and panoply of products can be overwhelming for media companies. “Sometimes it’s the hug of death,” Besbris conceded. “We want to innovate all over the place. Sometimes it feels like we are just swarming people with options.”

“What is great about them is, unlike Facebook or Apple, they are emboldening and supporting people who are already doing work in those areas rather than coming in with what they think is best,” said Sasha Koren, editor of the Guardian U.S. Mobile Innovation Lab. “The news partnership with Facebook is about helping news organizations use the products they already have, like Facebook Live. It puts publishers in a bind because they need to be experienced, and it would be hard to say no to money to do live video when live video is potentially a big piece of the landscape. For Facebook, it seems to be more about trying to engineer things among journalists to help the platform, rather than have journalism be strengthened so the platform can be of use.”

Others see these efforts as a reaction to mounting opposition and competition. The News Initiative came at a time when Google was not only facing European dissent but its referral traffic share was declining and its competition has grown, with the likes of Apple, Facebook and Snapchat launching their own publisher initiatives, media analyst Ken Doctor wrote.

With great power…

Others point out that at the end of the day, there’s still great inequality in the relationship. “The reality is that their powerful business model and financial clout meant that most publishers, despite laments and protestations, simply did not stand much of a chance in sustaining much of a collective effort of their own and were eager to get the Google support to industry efforts,” said Raju Narisetti, CEO of Gizmodo Media Group and former svp of strategy at News Corp, referring to Google’s funding of journalism works.

“All the nicey-nicey with publishers doesn’t matter if you can’t deliver benefit to publishers in the actual product. Product is king.”

Until AMP, many publishers just had a transactional relationship with Google. AMP was a turning point in that it necessitated close collaboration. It gave Google the ability to show its interest in working with small as well as big publishers, and send the message that it shared their commitment to the open web.

When AMP came, there was a lot of anxiety about what it would mean for publishers’ autonomy. Google created a working group of publishers early on to get their buy-in, which impressed Salah Zalatimo, Forbes Media’s svp of product & tech. “I’ve not seen it done this proactively and robustly,” he said.

Google has also won over publishers with the attention it provides in the form of case studies, guidance and outreach. Each week, Zalatimo videoconferences with a Google team that help him get the most out of its products like AMP and Progressive Web App. “It’s allowed us to get our PWA much further along, must faster than we would have otherwise; they had a talk last week connecting AMP and PWA and featured us,” he said. “We don’t have that with Facebook.”

More fundamentally, AMP is seen as more publisher-friendly than Facebook Instant Articles. It’s open-source, so theoretically, publishers can bend it to their will to some extent, which is different from Instant Articles. Many publishers have said that monetizing on AMP is on a par with their own sites, and many also are getting increased search traffic there.

The friendly face

The public face of Google’s charm offensive is its head of news, Richard Gingras. Gingras has been evangelizing the message that Google and publishers have mutual interests. He’s had a long association with high-quality journalism, having been CEO of Salon Media Group and helped found the Trust Project, an effort to figure out how trustworthy journalism can break through the clutter, and which Google helps fund.

Gingras isn’t just a high-level Google exec with journalism experience, he has direct influence over product, said Vivian Schiller, a former Twitter and NPR executive. That wasn’t the case when she was at Twitter, she said. “That cannot be overstated,” she said. “At the end of the day, all the nicey-nicey with publishers doesn’t matter if you can’t deliver benefit to publishers in the actual product. Product is king.”

Publishers still have plenty of sticking points with Google. Search is still a black box, although at least it’s mysterious to everyone. AMP is eating the web, but some publishers say they still can’t monetize their AMP pages as well as their regular mobile pages. AMP also limits publishers’ ability to replicate elaborate story formats, and for some publishers, that’s part of their signature brand. It’s nice that Google’s responsive and AMP is flexible, but that also shifts work to publishers, and puts heavier burden on small ones that are light on resources.

“That’s always putting the onus back on publishers,” Koren said. “They haven’t satisfactorily said, ‘We understand this is an issue.’ And monetization is an issue.”

And the risk of seeing Google — or any platform — as a good friend is that publishers may grow too dependent on it for revenue and traffic, which could be a problem if the platform’s strategy changes and stops being aligned with publishers’.

The New York Daily News has a single Google account team serving it, which gives the platform a holistic view of the publisher’s needs, a position that Facebook is still trying to catch up to, said Grant Whitmore, evp of digital at the tabloid. For now, that makes life “pretty easy,” he said. On the flip side, he said, “It’s not 100 percent altruistic; the more they help, the more we rely on them.”

More in Media

Digiday+ Research: Dow Jones, Business Insider and other publishers on AI-driven search

This report explores how publishers are navigating search as AI reshapes how people access information and how publishers monetize content.

In Graphic Detail: AI licensing deals, protection measures aren’t slowing web scraping

AI bots are increasingly mining publisher content, with new data showing publishers are losing the traffic battle even as demand grows.

In Graphic Detail: The scale of the challenge facing publishers, politicians eager to damage Google’s adland dominance

Last year was a blowout ad revenue year for Google, despite challenges from several quarters.