Anyone who has ever published a news story can tell you that it’s nice to have readers. That’s why every day, editors from dozens of the Web’s most reputable, highly trafficked business publications — Bloomberg, Business Insider, Quartz, to name just a few — pitch Dan Roth with their best, most timely stories. Roth and his team scour the pitches, looking to aggregate those most likely to resonate with their own audience of 86 million U.S. visitors.

A vast majority of the 7,000 posts that will go up on Roth’s site that day will be “edited” by machines, not humans, and targeted to the users most likely to read them: Managers will be served stories about leadership, pig farmers stories about pork belly prices.

But precious few stories will be hand-selected by Roth and his editors. These will be placed prominently, yielding hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of referral visits.

Editors rarely find themselves having to pitch stories to other editors outside their publication. But the kind of sway Roth has makes him quite unlike other editors. The outlet he edits? LinkedIn.

You may know LinkedIn as either a “professional network” or “that job hunting tool I once signed up for and now spams my inbox.”

But LinkedIn has also grown into a formidable media company. And when you examine the multiple aspects of LinkedIn’s media operation — a popular and growing native-ads business; tens of millions of potential “content producers” churning out nearly 40,000 posts per week at zero cost; a personalization engine; a staff of top-notch, in-house engineers able to refine those platforms and possibly develop new ones; an audience that’s larger, wealthier and more engaged than that of the average website and the luxury of not having two robust non-media-related revenue streams — you realize it may very well be the most formidable title in business publishing and Roth, the most powerful man in business journalism.

The social network

In October 2002, Reid Hoffman convened a team of four former colleagues to create a new kind of social network. The idea was simple: People would create profiles (digital résumés, essentially), add colleagues to a contact list and then share employment opportunities through that network.

LinkedIn officially launched seven months later on May 5, 2003. The first week brought in 2,708 signups, a fraction of the 8,000 Hoffman had been hoping for.

There were skeptics from the outset. “If you can’t search for people outside your own network, it is useless,” someone named Nadeem commented on a blog post about the launch. Another complained that the service would draw unnecessarily rigid lines between people’s personal and professional lives. And there was some concern that adding photos to profiles would turn the network into a dating site.

The doubters were soon proven wrong. By the end of 2005, LinkedIn had more than 4 million members and the company itself had grown out of three offices. The site introduced its first paid products that year: premium accounts for job-seekers and the recruiters hoping to hire them. LinkedIn became profitable in 2006 and in the black just a year later.

All the while, LinkedIn kept adding features designed to improve the user experience such as recommendations, which let users publicly brag on their colleagues, and InMail, an in-network messaging system. It even allowed users to start posting their potentially racy headshots.

But LinkedIn needed something to make its site “stickier.” Sure, it was great for job hunting, but users had little incentive to visit when they were gainfully employed. LinkedIn was even at risk of losing users to Facebook, which some had started using for professional networking.

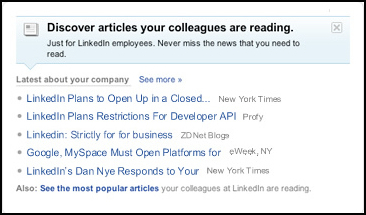

The solution was LinkedIn News, a homepage section that aggregated stories from more than 10,000 publishers and blogs, and displayed headlines specific to each user’s company, industry and network.

LinkedIn wanted its homepage to combine the influence of The Wall Street Journal (a daily must-read for the business set) with the focus of a trade publication (only scaled to each user) and the communicative aspects of a social network.

A mere homepage module would not be enough for LinkedIn’s news aggregation aspirations, though. The network was closing in on 100 million members and its debut on the New York Stock Exchange. If it wanted to satiate its members’ news appetites (and investors’ expectations), it would need to increase engagement.

On March 10, 2011, LinkedIn unveiled LinkedIn Today, the successor to LinkedIn News. LinkedIn Today would still aggregate and personalize stories but on a far vaster scale. Whereas LinkedIn News was a box filled with headlines, LinkedIn Today was its own webpage.

The launch was met with a similarly sized marketing campaign. CEO Jeff Weiner personally introduced the site in a press conference at the company’s Mountain View, California, headquarters. LinkedIn Today-branded food trucks stalked the streets of New York City and San Francisco, offering free coffee and iPad tutorials to random passersby. Former LinkedIn employee Mrinal Desai wrote, “LinkedIn could become The Wall Street Journal of social news” in a loving screed posted on TechCrunch.

Four months later, LinkedIn hired Roth away from Fortune to be its inaugural executive editor. The company wasn’t satisfied serving machine-aggregated links alone and wanted someone with editorial expertise to shape its burgeoning media business.

What LinkedIn would become in publishing would make LinkedIn Today look downright quaint.

The hack

There’s a stigma attached to journalists who leave the field for supposedly better-paying, less-stressful jobs. Perhaps he was never much of a journalist to begin with. A hack who couldn’t hack it.

Dan Roth was no such journalist. Conversations with several of his former colleagues elicited nothing but glowing praise, all of them gushing about his skills as a reporter, editor, manager and innovator.

“Dan is the package, professionally,” said Stephanie Mehta, who worked with Roth when she was deputy managing editor at Fortune.

Which invites the question: Why would a man apparently destined to become an editor-in-chief of one of the nation’s most renowned publications suddenly leave the industry?

Roth, a Northwestern graduate, started his journalism career in 1995 as a reporter at Triangle Business Journal, a business weekly that covered the Raleigh-Durham community in North Carolina. Roth soon found himself writing for a national audience, though; Forbes hired him as a fact-checker in 1996.

Once in New York, Roth started climbing mastheads. He worked at Forbes for two years before becoming a senior editor at Fortune.

Roth spent eight years at Fortune, eventually departing in March 2006 to help found Condé Nast Portfolio, a business monthly that first hit newsstands the following spring. Roth was the first writer hired by the upstart publication, but he left in late 2007 for a writing position at Wired.

What separated Roth from other talented reporters, according to Nick Thompson, then a senior editor at Wired, was his entrepreneurialism and creativity. For example, Roth spearheaded a venture-capital video game reminiscent of fantasy football. Wired readers would compete by “investing” in tech startups and seeing whose portfolio accrued more value. The project never got off the ground due to a lack of engineering resources, but Roth never stopped toying with how publications could use utilities, and not just stories, to foster a readership.

Roth’s vision and Internet savvy would eventually lead him back to Fortune. The magazine hired him in April 2010 to resurrect its website, which had been shut down during the financial crisis. Roth was already a well-accomplished reporter when rejoined Fortune. His April 19, 2004, profile of Donald Trump, “The Trophy Life,” was the Fortune cover story. When Henry Blodget, then a disgraced former Wall Street analyst, launched Silicon Alley Insider in 2008, Roth penned a 3,000-word feature on him for Wired. Few business reporters can say they have interviewed both Warren Buffett and Bill Gates. Roth once interviewed them simultaneously.

There was a minor catch to the new gig, though: There was no Fortune website to resurrect. In an odd attempt at cross-departmental synergy, Fortune and fellow Time Inc. publication Money had their digital presences subsumed by CNN, a Time Warner property. Rather than having their own websites, they published under a catchall vertical called CNNMoney.

But Fortune’s brand was one of the strongest in publishing at the time, its name literally synonymous with professional prestige. The Fortune 500, its annual ranking of the top-grossing companies in the U.S., was a brand unto itself. In his song “Mo’ Money, Mo’ Problems,” Notorious B.I.G. dreamed about one day gracing the cover of Fortune. It was the ultimate sign of having made it.

But the CNNMoney partnership was disastrous for Fortune’s online brand: Fortune’s name was even buried on the URLs of its own stories, which were: “money.cnn.com/date/article_title.fortune.” Roth was undeterred, though, attacking the problem with an inspiring vigor.

“You’d leave a meeting with him and think, ‘This is going to be really cool,’” said Scott Olster, whom Roth hired as Fortune.com’s associate editor. “He made you excited about the possibilities.”

When Fortune magazine released its signature Fortune 500 issue in May 2011, for example, Roth thought to develop a Web app that would fuse the list with LinkedIn’s database. Called Fortune 500+, the app allowed readers to see if they had any LinkedIn connections at Fortune 500 companies.

“It enables users to use all of our reporting in a way we’ve never done before,” Roth said then in an Ad Age interview. “We know people use our information as a tool. Why not actually build a tool for them?”

The app impressed more than just the trade press. LinkedIn CEO Jeff Weiner saw it and invited Roth to the company’s Mountain View, California, headquarters to discuss how LinkedIn’s trove of professional information could be better integrated into media coverage. A month later, Weiner called Roth with a job offer.

LinkedIn was featured on the April 2010 cover of Fortune, a year before Weiner’s fateful call. The story, “How LinkedIn will fire up your career,” was part profile of the rapidly growing professional network (60 million registered users, at the time), part service piece on how job seekers could use the platform to advance their careers.

Roth took his own magazine’s advice and turned to LinkedIn to advance his career, only he did so by accepting a job there.

The sell-out

Roth’s more forgiving journalism colleagues were puzzled by decision to join LinkedIn. Others felt Roth was selling out to work at a sexy Internet company.

“My first reaction was, ‘He should’ve gone before the IPO. He probably left some money on the table.’” Mehta said. “My second reaction was head-scratching.”

At Fortune, Roth was core to the business, Mehta added. LinkedIn meant entering an engineering culture with no editorial sensibility beyond algorithms and aggregation.

“Some of the older-school colleagues said, ‘Well you used to be a great journalist,’” Roth told me during a visit to LinkedIn’s New York City office. Situated on the 22nd floor of the Empire State building, Roth and his colleagues have a great view of the media landscape.

Now on the receiving end of journalist inquiries, Roth is treated more like a high-level executive than magazine editor. His comments are made under the close scrutiny of the kind of public relations representative Roth once had to wrangle with for access and answers.

But Roth — a compact, approximately 5-foot-9, 41-year-old — still has the brevity and candor of a journalist and the syncopated agility of a banjo picker (Roth himself plays in the old-timey clawhammer style). In just an hour, he covered everything from his start in journalism through the future of publishing on LinkedIn, providing just enough color to keep it interesting.

“It was not a compelling pitch, at first,” Roth said of Weiner’s job offer. “At this point, LinkedIn was just networks. I loved LinkedIn as a journalist. Finding people who had worked elsewhere was awesome, but I had never thought about it as a content company.”

But LinkedIn’s core functionality as a professional network is exactly what gave it a huge advantage when it came to building out is media operation. “At Fortune and everywhere else, we were constantly fighting to get the professionals’ attention,” Roth said. “The idea of building a content operation at LinkedIn where the professionals already were seemed incredibly valuable.”

Weiner’s only mandate to Roth was to figure out how LinkedIn could grow its media operation. How that was accomplished was entirely up to Roth and Ryan Roslansky, the head of content products at LinkedIn, however. After a year of experimentation, they realized that aggregating news stories wasn’t enough.

Roth’s focus when he started was LinkedIn Today, the recently launched business news portal. The hope was that human editors would complement the site’s aggregation algorithms. Roth hired two former Associated Press journalists to help him curate.

“Curating newsy content was not a distinguishing component for LinkedIn,” Roth said. “Even if our algorithm got 20 percent better and our editors got 20 percent better, there was no way for members to know the difference.”

Having Richard Branson and Deepak Chopra pen original blog posts for the site did the trick, though. Those were just two of the 150 “thought leaders” Roth recruited for LinkedIn’s influencer program launched in October 2012. Roth even successfully enlisted Barack Obama and Mitt Romney, then embroiled in a race for the White House, to be part of the kick-off.

Those 150 influencers produced more than 2,300 original posts in less than four months, an average of almost 20 posts per day. But LinkedIn still wanted more. It expanded the influencer network to 220 contributors in late January 2013, adding lesser-known experts, eventually capping membership at 500.

Roth’s chummy relationship with former Fortune colleague Eric Schurenberg, who had since become editor-in-chief at Inc. magazine, didn’t stop Roth from recruiting some of Inc.’s most popular writers, such as business author Jeff Haden and Salesforce CMO Michael Lazerow, to become influencers.

For Lazerow, Roth’s fraternity brother when they attended Northwestern together, the allure of writing for LinkedIn was the size of its audience. Some of his most popular pieces on Inc. drew in thousands of readers. His most popular LinkedIn posts, such as “Why Weirdos Outperform Normals,” attracted hundreds of thousands pageviews, however.

“It’s a distribution writers would never get through traditional media, especially writers for whom writing isn’t their full-time job,” Lazerow said. “Instead of one editor, its the network of people who receive all the content. They vote with their likes, shares and comments and they use that feedback to in essence create a whole new media property which has the distribution of a Mashable or BuzzFeed with the quality, you could argue, of The Wall Street Journal in some cases.”

Haden and Lazerow aren’t paid to write for LinkedIn, but said they’re indirectly compensated.

“Being an influencer has resulted in lots more traffic to Inc. posts, new professional opportunities, some cool new friends and a huge amount of feedback from readers,” Haden told Digiday.

LinkedIn needed help matching the influx of influencer posts to the users most likely to read them, so in April 2013, it acquired news aggregation app Pulse. Pulse replaced LinkedIn Today that November as the site’s news destination.

Using algorithms to evaluate the influx of posts became more important when LinkedIn opened its blogging platform to any and all members in February 2014.

“We knew that influencers was never enough,” Roth said. “Richard Branson gives you a small part of the professional world, but it doesn’t give you everybody. Everyone should have the chance to say what they know.”

But the influencer program worked largely because it was selective. By giving access to the masses, LinkedIn risked diluting the quality of articles posted.

“I was personally a little disappointed when they opened it up to everyone because there’s more competition for my stories to do well,” said Shane Snow, CEO of content marketing firm Contently and a LinkedIn influencer.

LinkedIn decided upon a multi-tiered editing system. The first of line of defense would be an algorithm that filtered out spam posts. Any post that passed that test would be shared to the author’s network. If the post elicited a certain number of comments or shares, it would be flagged as popular and posted in Pulse. LinkedIn’s human editors would also scan for stories they wanted featured in Pulse as well.

This arrangement persists today, and it’s what allows LinkedIn to “edit” the 5,000 blog posts it publishes each day.

The data

Journalists no longer question Roth’s decision to move to LinkedIn, nor would Roth have to defend himself if they did. The numbers speak for themselves: LinkedIn’s number of monthly unique visitors on desktops in the U.S. has increased by more than 11.9 million (or 36 percent) from Roth’s start in July 2011 to August 2014, according to comScore.

Quantity of visits has not come at the expense of quality, either. Rather, growth has corresponded with an increase in how often LinkedIn users visit the site each month. In July 2011, U.S. users came to the site an average of 3.8 times per month, according to comScore. The average reached 5.9 visits this August, a 55 percent jump.

Mobile remains an unsolved puzzle for many business outlets, but not LinkedIn — its mobile audience grew by more than 21 million visitors in just five months this year. (ComScore changed its mobile-tracking methodology in March, and LinkedIn’s mobile audience registered as significantly lower prior to then.)

“The network has been there for years,” Lazerow said, “but the content keeps them coming back and engaged.”

If reach and engagement metrics aren’t enough to attract an advertiser’s attention, then LinkedIn’s disproportionately wealthy user base likely will. More than 40 percent of LinkedIn visitors earn more than $100,000 per year, higher than 31 percent average for the entire Web, according to comScore. LinkedIn also outranked all the major social networks — Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and Tumblr — on comScore’s buying power index, which divides the buying power of a website’s audience by the Web average.

The numbers have been reflected in LinkedIn’s ads business: Revenue from LinkedIn’s “Marketing Solutions” team was $106 million in the second quarter of 2014, up 44 percent from the same quarter a year before.

Much of this growth has been fueled by its sponsored-updates ads, LinkedIn’s take on in-stream, “native” advertising. Like promoted tweets and promoted Facebook posts, these ads allow brands to display messages within Pulse’s content stream. Marketers love them: Sponsored updates constituted 28 percent of LinkedIn’s “Marketing Solutions” revenue in the second quarter this year, up from 23 percent the previous quarter, 15 percent the last quarter of 2013 and just 7 percent in third quarter of 2013.

Dell, for example, has made LinkedIn a focal point of its business-to-business marketing campaigns. The brand teamed up with research firm IDG this March to establish a niche LinkedIn group called End-to-End Solutions for IT Pros. LinkedIn supplies Dell with data on what’s trending among IT professionals. IDG — which is paid by Dell to maintain the group — then uses that data to inform what it should be posting.

He also encourages Dell employees — the company’s “subject matter experts” — to engage in LinkedIn groups themselves and “build their own brands.”

“The benefit is not lead generation, it’s understanding the business and technical challenges our community is facing,” Jones said.

‘It’s complicated’

Increasingly, though, LinkedIn’s editorial success has come at the expense of the rest of the business media. There was a time when publishers actually considered LinkedIn more ally than threat. Prior to founding its influencer network, LinkedIn was a steady supplier of referral traffic. Indeed, some business publishers optimized for sharing on LinkedIn much in the same way so-called viral sites now do with Facebook.

LinkedIn used to constitute a “substantial” amount of Inc.’s traffic, Schurenberg said. That all changed, though, once LinkedIn started publishing original stories.

Roth said publishers “have been crowded out by the native content on LinkedIn” and a forthcoming partnership between LinkedIn and business publishers would likely fix that. He declined to share the details of that initiative, though.

LinkedIn has already started working closely with The Atlantic, Bloomberg and CBS, helping them monetize their stories via a sponsored-content brokerage. The partnership allows advertisers to slap their brands on those publishers’ stories and target them at certain LinkedIn users. The publishers are paid in pageviews and, and in turn, incremental ad revenue.

“LinkedIn’s not at the level of a Google or Facebook as a traffic referrer,” comScore analyst Andrew Lipsman said, but it certainly has the potential to be. Just as Facebook gave rise to viral publishing sites, LinkedIn could set off a business publishing boom, Lipsman added.

But the relationship between publishers and LinkedIn is, to borrow some Facebook parlance, complicated.

Any publisher would certainly welcome the opportunity to get in front of LinkedIn’s audience. But the short history of digital publishing is littered with cautionary tales about relying too heavily on a single form of referral traffic.

“Publishers are definitely losing this battle with LinkedIn,” said Adam Kleinberg, CEO of digital agency Traction and frequent LinkedIn contributor. “Where LinkedIn used to be one of their top referrers, it now has a limited interest in driving traffic to their sites.”

Indeed, Roth’s own explanation for why referral traffic has dropped — that the sheer number of posts created by the contributor network has diluted attention — was similar to how Facebook justified decreased organic reach for brands, a change that rankled Facebook’s relationships with agencies and their clients.

Publishing experts are split on how large a threat LinkedIn poses.

Forbes, whose business model is almost indistinguishable from LinkedIn’s media operation now that it has embraced native advertising and an open contributor network, dismissed LinkedIn as competition. “If anything, it validates the model we put in place four years ago,” Forbes cro Mark Howard said. Howard said that Forbes has “tremendous reach” on LinkedIn but, oddly, sees little referral traffic from the platform.

Jeff Haden, the author, had another take. “No one has the time to read everything, so certainly LinkedIn steals attention from other sites,” he said. “But great content published on LinkedIn can definitely drive traffic back to other sites. I’ve had year-old Inc. posts receive five and six-figure hits simply because I placed a relevant link in a new LinkedIn post.”

The future

Roth admitted that LinkedIn’s editorial goal — “to get the world’s professionals sharing the insights that they have to make everyone else better” — comes off as corny.

And what performs well on LinkedIn aren’t exactly the fruits of hard-nosed, original reporting. The three most popular posts on the site on Sept. 23 were “Why Successful People Never Bring Smartphones Into Meetings,” “When You Stop Checking Facebook Constantly, These Things Will Happen” and “Chipotle’s Brilliant Hiring Process,” an analysis of the company’s careers website.

But if a business publication’s true goal is to have a tangible impact on its readers’ professional lives, then LinkedIn may be the most successful publication not in print.

“From what people are reading and how they’re commenting, we know that they feel like career ladders are broken. People don’t get training anymore. People don’t know what they’re good at and what they’re bad at; they’re just getting moved up and then they’re managing people, but they’ve never learned how to do it,” Roth said. “Reading what other people have done — real people — what they think, makes people smarter and they find connections.”

Weiner is still not satisfied with the editorial operation, Roth said. For one, he views the human editorial process as unnecessarily cumbersome. He hopes Roth can train LinkedIn’s algorithms to identify quality completely on their own. Roth is tasked with making his current role obsolete.

Robots have already proven capable of writing straightforward news stories like recaps of companies earnings announcements. LinkedIn proposes to render editors irrelevant, too.

And yet, right next to the reception desk in LinkedIn’s New York City office is a rack of the very magazines LinkedIn stands to disrupt: Fast Company, Forbes, Fortune, Inc., Wired. “It’s clear now that LinkedIn is closer to what journalism is becoming,” Schurenberg said of Roth. “LinkedIn and Fortune are converging. That’s the irony.”

It’s in talking about LinkedIn’s future that Roth exudes the infectious excitement that made him so beloved by his Fortune reporters. Getting algorithms to recognize quality at scale will free up editors to pursue the ambitious projects Roth had always wanted to develop as a magazine journalist.

Weiner convinced Roth to join LinkedIn partially by assuring Roth that he could always go back to the traditional media world if he wanted to. But now that would mean leaving the most powerful job in business media.

“When I joined LinkedIn no one internally knew what an editor was supposed to do. And externally, people in journalism didn’t understand what an editor was going to do at LinkedIn,” Roth said. “Now, the questions are gone, internally and externally, and that’s a great feeling.”

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly listed Roth’s height as 6 foot tall.

More in Media

In Graphic Detail: The scale of the challenge facing publishers, politicians eager to damage Google’s adland dominance

Last year was a blowout ad revenue year for Google, despite challenges from several quarters.

Why Walmart is basically a tech company now

The retail giant joined the Nasdaq exchange, also home to technology companies like Amazon, in December.

The Athletic invests in live blogs, video to insulate sports coverage from AI scraping

As the Super Bowl and Winter Olympics collide, The Athletic is leaning into live blogs and video to keeps fans locked in, and AI bots at bay.