Rich Antoniello’s favorite swear word is “fuck.”

“You can ask every one of my employees, and they would all know that,” he said. “It’s like an adjective or adverb for me. It just gets added in, and it doesn’t sound particularly offensive coming from my mouth — or at least that’s what I’ve been told.”

The CEO of Complex Media, a network of fashion and pop culture sites targeted at young men, doesn’t pull many punches, which can make him come across as overly blunt or even “a bit of an asshole,” as he admits. But Antoniello, 44, said that his top job isn’t to be nice but rather to help his company win — which often means saying exactly what he’s thinking.

One thing he’s particularly forthcoming about is his competition, and Complex’s relation to it: Vox Media, in his estimation, is “all over the place,” while BuzzFeed’s “revenue trails behind its influence.” Vice, for which he saves his sharpest barbs, is mostly “overrated,” a production house and impressive brand more than a real media company.

Such honesty, while rare among media executives today, feels at home at Complex Media, which has since 2002 built its brand on authenticity, youth and “realness.” Antoniello, the company’s head since 2003, is both a product and the origin of that outlook. Raised in the blue-collar Canarsie, Brooklyn, neither his father, a UPS deliveryman, nor his mother, who raised him full time, went to college. Antoniello said he had to claw his way to the top without a blueprint for how to do it, leaving him with a deep-seated appreciation for scrappiness and an affinity for people “who have a bit of a chip on their shoulder.”

That outlook has seeped into Complex’s DNA. At a time where the likes of BuzzFeed and Vice are raising big venture capital rounds at higher and higher valuations every six months, Complex stands as a rare example of how you can build a media company organically. It has raised just $39.5 million over the past 12 years to fuel its growth, far less than the $96.3 million and $570 million BuzzFeed and Vice have raised, respectively. In Antoniello’s eyes, Complex is the “consummate underdog.”

“What we’ve done is like going to the gym, losing weight, and putting on muscle at the same time,” he said, using one of his multiple sports analogies to explain how he has built the company. “We had to self-fund this. Unlike a lot of other companies, which go out and raise millions and millions that they go burn, we had to stay disciplined. There are a lot dead companies on the side of the road that didn’t do that.”

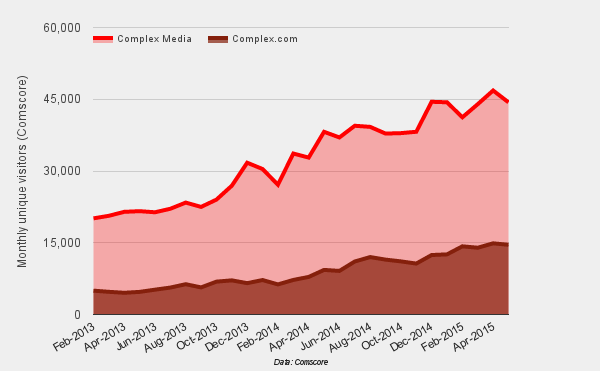

Complex’s traffic growth has been gradual but consistent. Complex Media overall got 44.4 million monthly unique visitors in May, according to comScore, double the same point from 2012. Complex.com’s share of that has also tripled to 14.6 million monthly uniques during that same span.

The Reluctant CEO

“Slow and steady” isn’t a popular business strategy for media companies these days. Legacy ventures are more worried about the next few quarters than the next few decades, forcing them to make short-term moves at the expense of their long-term viability and brand. Young venture-backed outfits and their investors, in contrast, are reverse-engineered for big-ticket exits, less so about what comes after them. But Antoniello, who has stayed at Complex’s helm for over a decade, realized that media is a marathon, not a sprint, and it often takes many years before today’s investments pay off.

“This is a brand. We’re a brand as much as we are a business,” he said. “There are lot of people out there that are just digital businesses that have a lot of scale but don’t really mean anything to the end consumer. Complex is a brand that means something.”

That brand has become a differentiated one the eyes of agencies. “There’s really nothing comparable out there,” said Sadira Furlow, vp at Commonground Marketing, who has worked with Complex on behalf of Miller Lite and Verizon. “Out of any brand that I’ve seen they live at the epicenter of the culture. If anyone gets it, they do.” She called Complex her “secret weapon.”

For Antoniello, that affinity for branding didn’t always exist. Antoniello was good at math as a child. As he grew up, he thought the skill would land him at a cushy gig in finance and accounting. The goal: to never have to worry about money again.

Something got in the way though: In 1992, while a junior at Binghamton University, Antoniello landed an internship at BDBO Worldwide, a formative experience that he said gave him a taste of media and the creative side of the business — and pulled him away from Wall Street. After graduating, he spent two years as a media planner at Saatchi & Saatchi, after which he jumped over to Men’s Journal and, two years later, National Geographic Publishing, where he spent four years as its national sales director.

When Complex came calling in late 2002, Antoniello, who was 30 at the time, was torn. “I’m definitely a reluctant CEO. This wasn’t my goal,” he said. “I was a successful sales guy, so I thought I’d end up running revenue somewhere, not running a whole company.”

Despite that, Antoniello realized that he had developed an acumen for running both sides of the business — from the bean-counting to the more fuzzy brand-building that running a media company often requires. “I realized I could be more effective within each of those silos by being in control of all of them.”

All of that, said Complex founder Marc Ecko, is what made Antoniello the right fit for the job. “He has that rare quality of being both a left-brain and right-brain person at the same time,” he said.

The rise of the “convergence consumer”

The nexus of brand and commerce was core to the Complex mission from the start. Ecko, who founded the massively successful urban clothing brand Ecko Unltd, knew that fashion had as much to do with lifestyle as it did clothing. Fashion, he knew, sat at the intersection between hip-hop, sports and pop culture, and that it was hard talk about one without touching on the others. So in 2002, he created Complex, the print magazine.

From the beginning, the magazine’s core reader was the “convergence consumer,” Complex’s term for a consumer whose identity is more closely tied to a series of overlapping vertical interests than just their age, race and gender. The theory was a new one back in 2002, when the Internet was still relatively young and when advertisers and agencies were used to structuring their approaches around broad demographics, not niche interests.

“Our thesis was antithetical to that: We said that if you took those topics in aggregate and cross-pollinated them, you’d create something much bigger and more intellectually honest profile of what American popular culture actually is,” Ecko said.

The formula worked. Complex eked its way to profitability after just three years. But the writing was the on the wall. By 2006, readers were rapidly going digital, taking the advertising dollars with them — and potentially leaving print-heavy publishers scrambling for influence.

“We had McDonalds, Coca-Cola and Pepsi coming to us and saying, ‘We want to give to you more money because you’re a differentiated brand, but you’re a print magazine with 2 million circulation. There is only so much money we can give you based on your reach,’” Antoniello said.

So in 2007, Complex went all-in on digital with the launch Complex Media Network, a vertical-focused network of preexisting, independent sites focused on core Complex topics such as sneakers (NiceKicks), music (NahRight) and fashion. Once signing up the sites, Complex took over their ad sales and audience development, opening the sites to advertisers they wouldn’t get otherwise and giving Complex significant rolled-up audiences to approach agencies with.

The pivot was successful in that it weaned Complex off of its print revenue. Today, less than 2 percent of Complex’s revenue comes from print.

“Print is on auto-pilot for us right now. If you’re spending time and resources developing that part of your business now, you’re running toward yesterday,” he said. “You have to invest in tomorrow.”

Early to the party

With print on the back burner, Complex has turned its attention to new businesses: sponsored content and video. In 2013, Complex teamed up with PepsiCo to launch Green Label, a Mountain Dew-branded sponsored-content hub. While such deals have become common, Green Label was an early — and, at the time, rare — example of a publisher creating a deep, ongoing campaign with a brand rather than a one-off transaction deal.

It has also worked with McDonald’s, Levi’s and Adidas on similar deals. Sponsored and branded content has quickly become core to Complex’s bottom line: Last year, 30 percent of the company’s revenue came from branded content. This year, it will be closer to 50 percent.

And then there’s video. In mid-2013, Complex raised $25 million to help spearhead its video efforts with Complex TV, a video hub home to Complex original such as “Fashion Bros!” and “Sneaker Shopping.” Complex also pushed into video-based culture news with Complex News, which dishes on the latest in pop culture (Antoniello has no interest in pushing into hard news). Complex’s videos get over 150 million views across its own properties, Facebook and YouTube. The video business, which includes pre-roll, as well as branded and sponsored video, will represent 20 percent of Complex’s business this year, and 37 percent in 2016.

“Print companies allowed themselves to be defined by their distribution platforms, not their brands and value they were adding,” Antoniello said. “We took what our consumers were saying was the best shit around and leveraged that in the digital space.”

Complex isn’t done growing. Harkening back to the company’s commerce roots, Antoniello is mulling over ways to make Complex a stronger platform for driving direct purchases. He also hinted at potential acquisition opportunities and even the chance that Complex’s original video could land on a cable network. “Having an entire cable channel is not something that’s wildly interesting to me. Getting some of our very vertical shows exposed to either cable and or network TV is potentially much more lucrative and more fitting of what we’re trying to.” (Contrast that with Vice, which has pushed hard to land its own cable channel).

“We don’t do things because they’re business principles or because that’s where the dollars are,” he said. “We don’t chase ad dollars — ever. We chase our consumers because that’s where the actual value is.”

More in Media

Digiday+ Research: Dow Jones, Business Insider and other publishers on AI-driven search

This report explores how publishers are navigating search as AI reshapes how people access information and how publishers monetize content.

In Graphic Detail: AI licensing deals, protection measures aren’t slowing web scraping

AI bots are increasingly mining publisher content, with new data showing publishers are losing the traffic battle even as demand grows.

In Graphic Detail: The scale of the challenge facing publishers, politicians eager to damage Google’s adland dominance

Last year was a blowout ad revenue year for Google, despite challenges from several quarters.