In 2011, British member of parliament Jo Swinson ordered Lancôme to take down London billboard ads featuring Photoshopped images of famous women — Julia Roberts and Christy Turlington. The altered images, she said, were “not representative of the results the products could achieve” and gave women unrealistic and false expectations of what women should look like.

Back in the U.S., the move caught the eye of Seth Matlins, who had just left his big marketing job as CMO of Live Nation to start Feel More Better, a site to help empower girls and women to be happy and healthy. Initially moved to write an opinion piece about Swinson’s actions, Matlins decided to go a step further.

“I asked myself the question if the British government is doing that, who is doing that here? Who is protecting my daughter from these false and unrealistic expectations?” he asked. “And I looked around and I didn’t see anybody, so I said we will.”

Over the past three years, Matlins has been working to raise awareness of the ad industry’s harmful photo-manipulation practices. His work has now culminated in the Truth in Advertising Act, a bill currently making its way through Congress that Matlins wrote in partnership with the Eating Disorders Coalition. He has also spearheaded a change.org petition asking the Federal Trade Commission to adopt the terms outlined in act so that children don’t grow up with unhealthy and unattainable notions of what they should look like.

Matlins recently spoke with Digiday about the details of the Truth in Advertising Act, why it has been hard to get the ad industry to support the cause and why the Dove “Real Beauty” campaign isn’t actually all that great. Excerpts:

Can you explain what exactly the act is?

We are asking the FTC to bring all stakeholders together — media advocates, the ad industry — and come back in 18 months with a regulatory framework on how we remedy the problem. While the problem skews disproportionately to women and girls, it is not limited to them. We are asking the FTC to stand up for truth in advertising. We are asking them to exercise their mandate as America’s consumer protection agency and work with everyone who has a vested interest in this.

What kind of advertising practices in particular are you targeting?

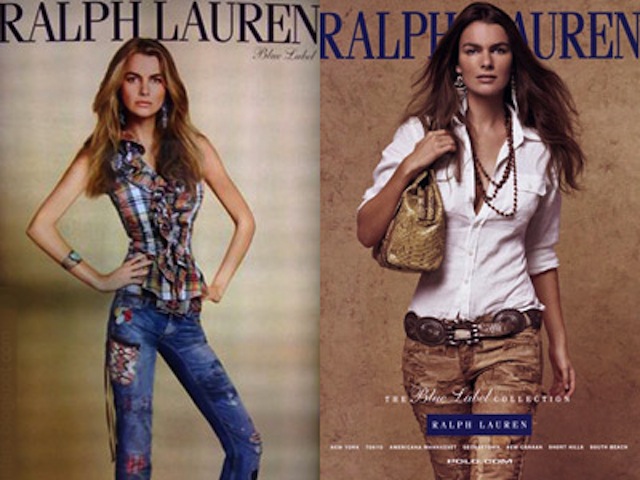

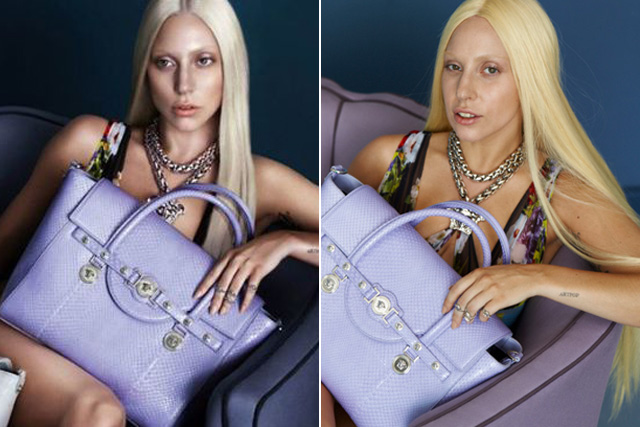

The bill is focused singularly on advertising — we aren’t talking about editorial or individual expression. What we are interested in are material changes, like changes to shape, size proportion or removal or enhancement of features — changing bust lines, removing wrinkles. Those alterations become misrepresentations and deceptions in the service of selling something. This bill has the potential to challenge, if not threaten, the advertising status quo.

What are the biggest challenges you face in getting this act passed?

We need more congressional sponsors. We need a Senate companion bill and Senate support, and we need enough voices and support to hopefully turn this bill into a law. Of course, the FTC doesn’t need a bill or a law to act. The FTC can choose to act and honor the ask made by the Truth in Advertising Act at any moment, and we are supporting that with a petition that launched Monday on change.org.

Have you been able to get support from the ad world?

Individuals within the ad and marketing world absolutely. Organizations, in particular the bodies representing the ad industry, not so much. I personally invited the 4As [American Association of Advertising Agencies], the NAD [National Advertising Division], the Children’s Ad Bureau and the AAF [American Advertising Federation] to our congressional briefing, and with the exception of the 4As and the NAD who said they couldn’t make it, the others have not responded or said anything at all, and none of them showed up. The industry as a $400 billion enterprise domestically, I think we will see as much resistance from those industry bodies as you see from any traditional vested interest who likes the status quo the way it is.

What do you think of the Dove “Real Beauty” campaign, and what is stopping more brands from doing things like that?

It is better than many other ads out there. It is still reinforcing beauty as a primary validator of self-worth and self-confidence. I do acknowledge it is hard to sell a beauty product without speaking to beauty. I am cognizant of the fact that Dove is owned by Unilever, which owns Axe, and Unilever brands have been sexualizing and objectifying women far beyond the Dove campaign. I couldn’t get Dove to even reply on Twitter to support what we were trying to do.

But the manipulation of images and the objectification of women helps sell products, which speaks to a larger cultural problem about what our society values.

When I wrote the first article for HuffPo, they changed the title. When I submitted it, it was “Is Pop Culture the Biggest Bully of All?” They changed it to “Should Beauty Ads be Legislated?” As I said, this isn’t the silver bullet. We aren’t talking about the cover of Vogue, we are talking about the ads in it. Parents do need to teach their children how to love themselves, but while parents are the first and the last line, advertisers do need to be accountable for not just what they sell, but how they sell it. I’m a fan of commerce. This isn’t anti-commerce or advertising; it’s a health issue.

You write that 53 percent of 13-year-old girls are unhappy with their bodies. By the time they are 17, that number is up to 78 percent. What is it going to take to get advertisers to change?

The data showing the damaging effects of deceptive advertising hasn’t been enough yet. The ad community will move when they are certain of the upside for commerce or when forced to by legislation or litigation. Disclaimers like “Objects in mirror may be closer than they appear” or the small print on the screen that says “Professional driver, closed course” — advertisers don’t do this out of the goodness of their hearts. It’s to protect themselves from litigation. But look at CVS and how they decided to stop selling tobacco products despite the economic and bottom-line impact, bravo. Stepping up to do the right thing by the people they serve even if there is near-term economic consequence. We need more CVS’s.

More in Marketing

‘Still not a top tier ad platform’: Advertisers on Linda Yaccarino’s departure as CEO of X

Linda Yaccarino — the CEO who was never really in charge.

Questions swirl after X CEO Linda Yaccarino departs from the platform

Her departure marks the end of two tumultuous years at the platform.

Creator marketing has the reach — CMOs want the rigor

The creator economy got big enough to be taken seriously.