Secure your place at the Digiday Media Buying Summit in Nashville, March 2-4

How SSPs use deceptive price floors to squeeze ad buyers

Header bidding is unloading a symphony of destruction on ad tech, and supply-side platforms are adjusting by jacking up their price floors in hidden ways.

Rather than setting price floors as a flat fee upfront, some SSPs are setting high price floors after their bids come in as a way to squeeze out more money from ad buyers who believe they are bidding into a second-price auction, which is where the second-highest bid determines the price the impression gets sold for. The reason price floors are critical is because they determine the minimum value that an impression can be won for. While sell-side platforms have been known to mislabel the type of auction they run, this tactic is different since it allows SSPs to technically run a second-price auction while charging ad buyers as if the highest bid is winning the impression.

In a second-price auction, raising the price floors after the bids come in allows SSPs to make extra cash off unsuspecting buyers who thought they could secure an impression with a high bid but end up paying a much lower price. This practice persists because neither the publisher nor the ad buyer has complete access to all the data involved in the transaction, so unless they get together and compare their data, publishers and buyers won’t know for sure who their vendor is ripping off.

“With the onset of header bidding, these games kicked into full force,” said a demand-side platform exec requesting anonymity. “SSPs are trying to differentiate themselves to publishers based on yield, and they get that yield by ripping off the buy side.”

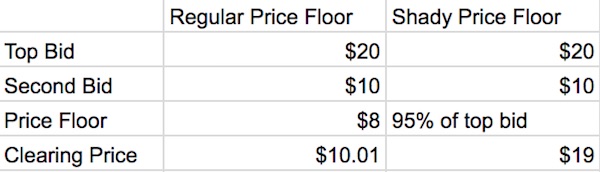

OpenX recently teamed up with an unnamed DSP so they could get data from both the buy and sell sides to study how auction mechanics are being gamed. Across several SSPs, they found that even when buyers bid as high as $50 on an impression, the SSPs would set their price floors at 95 percent of what the highest price was. The chart below shows how this would work to the SSPs’ advantage.

Drew Bradstock, svp of product at Index Exchange, said that before header bidding allowed SSPs to simultaneously bid on the same inventory, SSPs were more likely to have unique inventory, and they could make money by simply selling the inventory they had access to and taking a cut. But with header bidding, several SSPs are bidding on the same inventory, and only the one that wins the auction will make any money.

So to make sure they win the auction, these SSPs want a high clearing price, and one way to make sure there is a high clearing price is to set high price floors so the highest bid (rather than the second-highest bid) gets passed to the ad server. Bradstock stressed that there are good reasons to have first-price auctions or raise price floors, but that this information should be transparent to ad buyers because their bidding strategies will be influenced by what type of auction they think they’re in.

When header bidding started gaining traction, SSPs that were losing auctions adapted by increasing the cut they took for each impression that they won, said the DSP exec. But following the Guardian-Rubicon Project lawsuit, publishers started purging high-margin vendors, which has made SSPs hesitant to raise their fees. In response, SSPs turned to raising price floors incognito since that could benefit their publisher clients in the short term by increasing the CPMs they get.

Changing the price floors after the bids come in is like changing the rules of a game that is already underway. SSPs pull this off by inserting code into their auction that automatically raises the price floor just before the publisher’s timeout, the DSP exec said.

For example, a publisher might give SSPs 0.5 seconds to respond to ad calls before moving on without them. The SSP will collect whatever bids come through in 0.49 seconds, and then just before the auction closes, it will set the price floor to 95 percent of whatever the highest bid happens to be.

Buyers could spot seedy vendors if they compared their transaction data against publishers’ data. But meeting with individual publishers is only worth buyers’ time if they make large buys on those particular websites. However, the ad supply chain is engineered to have as deep a pool of publishers and advertisers as possible, which leads ad buyers to purchase inventory from thousands of sites for a single campaign. For the majority of those sites, the buyer won’t have time to set up meetings to compare data, which helps shady vendors remain hidden.

Using deceptive price floors is hardly the only questionable tactic SSPs use. They also misstate which publishers they represent and resell inventory without publisher authorization. And DSPs are guilty of their own sins for using misleading definitions of clearing price and sneaking in audience segments with unclear markup.

At some point, the shenanigans become overwhelming for ad buyers.

“We don’t know how prevalent [the tricks] are or who is guilty of it, as we don’t see that level of transparency,” said an ad buyer requesting anonymity.

More in Marketing

Future of Marketing Briefing: AI’s branding problem is why marketers keep it off the label

The reputational downside is clearer than the branding upside, which makes discretion the safer strategy.

While holdcos build ‘death stars of content,’ indie creative agencies take alternative routes

Indie agencies and the holding company sector were once bound together. The Super Bowl and WPP’s latest remodeling plans show they’re heading in different directions.

How Boll & Branch leverages AI for operational and creative tasks

Boll & Branch first and foremost uses AI to manage workflows across teams.