Secure your place at the Digiday Media Buying Summit in Nashville, March 2-4

It’s ad agency TBWA/Chiat/Day L.A. president Erin Riley’s ninth Zoom meeting of the day. Or so she thinks. “It all starts to blur together,” said Riley, who is hunkered down in her home in Los Angeles with her daughters and her husband.

Zoom is a small challenge in the broad scheme of the current situation. But it does add a toll to Riley, who finds video calls taking over her entire day. It begins first thing in the morning for work, then there are the calls she takes with her friends and family.

“It’s a real privileged problem to have in a time like this,” said Riley. “But it’s a problem.”

It’s Zoom fatigue. As millions of people stay indoors due to the coronavirus outbreak, business and pleasure has both moved to the virtual realm. That’s meant that nearly every single interaction most people are having is happening online — and whether it’s because of its ease of use or its ensuing ubiquity, it’s mostly happening on Zoom.

Of course, there is a privilege in being able to work like this. Suffice to say that in the absence of real human interaction, the ease of use of Zoom is the next best thing. It’s invaluable to connect with teams, friends, colleagues during a time that is uncertain at best and paralyzingly anxiety-inducing at worst.

Most companies have reacted to a new all-remote existence with a mandate to “over-communicate.” That has paid dividends in the early weeks, but for some has now led to a nonstop deluge of video calls that — let’s be honest –could simply be emails or Slacks. (Or even, phone calls!)

Zoom fatigue is exacerbated by how many interactions seem to have automatically moved to video chat, even if they were useless meetings to begin with, or could have been replaced by an email or a Slack. And even meetings or interactions that would have normally been done by that archaic method of communication, the phone call, have all turned to Zoom. For many, uncertain times — and probably seeing hardly anyone outside of immediate family — means video chat is the default.

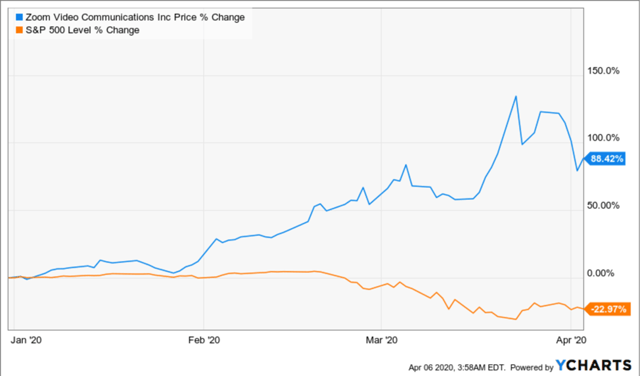

The rise of Zoom has been startling. What began as a better version of a Google Hangout, has entered the realm of shorthand. Who hasn’t been asked “do a Zoom” or simply “zoom”?

This growth isn’t just work, either. Family Zooms are now common, as are Zoom happy hours, Zoom classes, Zoom fitness instructions, Zoom meditations and more. One friend is planning a gender reveal on Zoom, and packages with “props” are arriving at all of our homes. It’s everywhere, ubiquitous, with screenshots of galleries of co-workers, friends and in my case, me with my Equinox instructor and 10 strangers doing a strength workout populating Instagram. It’s hard to tell if in some cases, it’s some kind of flex, your popularity (“look how many friends I have! look how many plans I had!”) distilled down onto a screen.

The cultural moment Zoom is having can be seen in how fashion has rushed to catch up with Zoom-ready tops and accessories. (Tie-dyes, bandannas, those dreaded headbands, and of course, earrings for days — all very in.)

Zoom isn’t a replacement for real-life interactions. Every verbal tic, every slight eyebrow raise, and every other non-verbal reaction signs are overblown when you’re all gazing into your screen, populated by multiple giant heads.

As Steve Hickman, executive director of the Center for Mindful Self-Compassion puts it, it overloads visual cues — hyper-focusing on whatever is available on your screen, but also maybe processing other information such as your phone ringing, dog barking and an email and Slack coming in. “It is a stimulus-rich environment, but just like rich desserts, sometimes too rich is just too much,” wrote Hickman.

That’s given rise to a new set of annoyances. There are those coworkers who love a custom virtual background — playing puppies, lol! — and those who find them distracting and inappropriate. There is the inevitable communal cry, “You’re on mute.” There are the people who will not, ever, put themselves on mute, when they really ought to. There are the obligatory “home tours.” There are people freezing during inopportune moments. There are people playing pranks where they are so still it seems like they’re frozen due to a bad connection. (They aren’t! Isn’t that fun?)

People — not me, of course — can be triggered, not to mention baffled, by why in the world a colleague would leave on the loud ding notification whenever a Slack comes in, which is pretty much all the time. A colleague, who left his Brooklyn apartment for a suburban exile only lightly packing, has a “Zoom sweater” that appears whenever he needs to talk to people outside the office. Will he at some point add a second? (Editor’s note: I’m working on it, Shareen.)

The early weeks of working remotely meant Zoom gave us glimpses into our colleague’s home lives. We saw kitchens, living rooms, even bedrooms. We met children, pets, plants named Stanley. We wondered whether the globe in the background opens into a bar set, wouldn’t that be neat? One of your colleagues has a dungeon, that’s weird. This newness wears off. Sometimes a person just wants to get an answer, not have to go through an obligatory first five minutes of every meeting talking about whether your coworker moved rooms in their house or if they decided to wear a floral shirt, or have to wave hello when a spouse walks by. You wonder how long your particularly fashion-forward colleague will wear put-together “cozy” outfits (and post them on Instagram.)

And, of course, offices being offices, there is a catty side to Zoom. Can you believe the Ikea art? Is that Grisham on the bookshelf? Do you only have one room in your house? Are you drinking a Bud Light at virtual happy hour? Are you literally in bed?

Kat Vellos, a UX designer who works with professionals on connections and networking and wrote a book called “We Should Get Together,” said this was something she had been “nervously anticipating when the door got slammed on the outside world.”

There was already a “dangerously high level of screentime before this,” said Vellos. Now, it’s more, and there’s a barrier on top of regular discourse, punctuated with screens that freeze at inopportune moments and right when someone is about to say something important.

Plus, there are other issues: “On a video call, it feels necessary to be smiling all the time. It’s just the sense that our words can’t stand on their own. And as a black woman, I need to not be seen as angry, or just have resting bitch face. So I’m smiling. And I’m tired.”

“I’m feeling more drained at the end of the day versus our days in the office,” said Riley of TBWA/Chiat/Day, often because she is over focusing, trying to pay more attention, and also simultaneously hoping the meeting or check in can recreate the feeling of her company when everyone was together.

The other issue many are observing is more presenteeism.

As Riley says, if someone doesn’t have video on, or something else is going on, there’s a strange unsaid “What are you hiding?” feeling. For her part, she’s tried to communicate with her teams that it’s OK to not always have video on, and push back to say, take some self-care time if you need it.

“I work at a company that didn’t really do much of this work from home business,” said a marketing executive at a financial services company. “Now, we’re all doing it, so the pressure is on: Be on every call, every company happy hour, every manager check-in and catch up, react constantly make sure you’re being seen.”

Lest management think you’re taking a nap on the couch, watching TV, baking in the middle of the day, or just slacking off, Slack is always on. And that bleeds over into video.

It’s also more prevalent now that management is extra vigilant about checking in with their teams. (At least three CEOs I’ve spoken with over the past week noted that they were being extra communicative, holding multitudes of virtual happy hours and multiple daily check ins, plus weekly all-hands meetings and video messages) All good things, but not so great for the average employee who sees their Zooms adding up. There’s another element: It’s Paul Graham’s classic maker vs. manager problem, where managers have schedules that allow them to find open slots to have meetings in, while makers have to use days in ways where there are large blocks of time in which to “make.” For them, meetings are generally a problem. And with more meetings than ever in an effort to replicate connection, everything starts feeling seriously out of control.

“The point of the performative aspect is a huge problem,” said Vellos. “It’s a dance. Look at the dot light that’s the camera, look at their face. I just go back and forth all the time. All of these little dances we have to do to replicate connection.”

More in Marketing

Future of Marketing Briefing: AI’s branding problem is why marketers keep it off the label

The reputational downside is clearer than the branding upside, which makes discretion the safer strategy.

While holdcos build ‘death stars of content,’ indie creative agencies take alternative routes

Indie agencies and the holding company sector were once bound together. The Super Bowl and WPP’s latest remodeling plans show they’re heading in different directions.

How Boll & Branch leverages AI for operational and creative tasks

Boll & Branch first and foremost uses AI to manage workflows across teams.