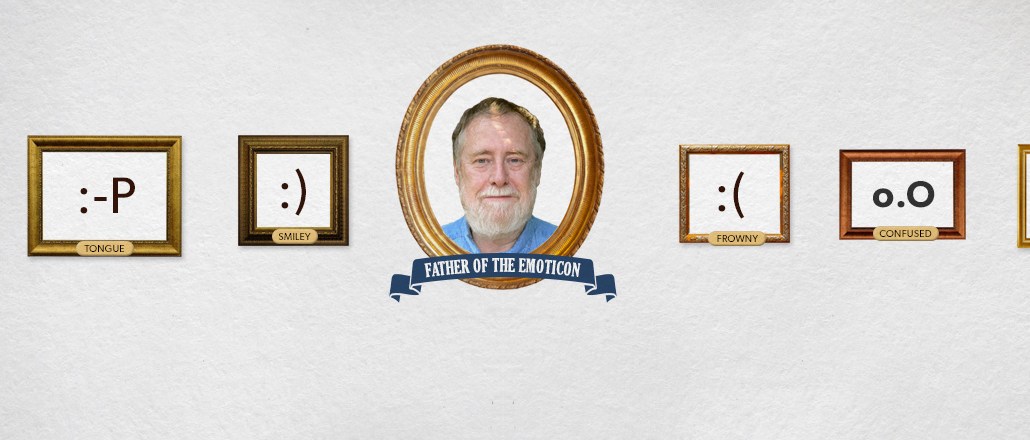

In 1982, computer scientist Scott Fahlman was confronted with a challenge: how to distinguish joke threads from serious offerings on an early online bulletin board for his students. And with three fateful keystrokes, the emoticon was born. :-)

It spread to other bulletin boards and, eventually, through email. Now, three decades later, the emoticon has given rise to the emoji. Type a colon and a parenthesis into your phone today and chances are it will automatically render as a yellow face.

But Fahlman, who unleashed an advance in communication over five millennia in the making, is displeased with what his baby has become. The father of the emoticon still finds it hard to understand why his creation became so big — and don’t even get him started on what he thinks of emojis.

Excerpts:

Where did the idea of the emoticon come from?

I try never to claim that I invented the emoticon because people always want to fight about that. But it was back in 1982. I was a relatively new professor at Carnegie Mellon working on computer science and artificial intelligence. Even in those days we had social media, but that was in the form of online bulletin boards — you could send an email to this place where everyone could see it. And we had to label this one particular thread to differentiate the jokes. People suggested putting an asterisk, but that didn’t seem very intuitive. It occurred to me that there were these smiley faces on t-shirts and balloons that was very big in the ’60s. And I thought that a smiley face of some kind would be really cool, so I wrote a three line post and suggested this thing. But I thought it would amuse the dozen or so people in that group, but it caught on. As soon as there was email, it spread virally.

Were you surprised by that viral spread?

When I first posted the thing, I had no idea that it would be popular. I thought it would last a day or two. I didn’t even save a copy. We found it 20 years later in the archives. But the thing developed legs, and within a month, we started seeing people making lists of all the different emoticons.

And now they’ve mutated, spawning emojis.

Much later, when it became consumer software in the 1990s, you started seeing those awful yellow circles. I don’t mind that so much, but I don’t particularly like them. I think they’re ugly. And maybe it’s because I didn’t invent them. I kind of have an emotional attachment to the original kind. But what was the most annoying was that Microsoft, AOL and others turned on conversion by default. So I’d type my nice text emoticons, and it would grab them and turn them into something else that I didn’t like. Sometimes it happens in the middle of my computer program too. If people enjoy emojis, great. But I don’t.

Why not?

I don’t see any real creativity in making yellow circles with a smiley face. Then there were more of those, and they started looking like actual chefs and firemen and stupid things. And then you got the animated ones and the pornographic ones. There’s a whole industry out there now coming up with emojis. I once in a while get a message from a teenage kid in South America or something complaining that there is no volleyball emoticon and why don’t I tell Apple to fix that. Well, I’m not in charge, folks. I don’t even like these.

Do emojis make you sad?

In a way, these all descended from the original thing I did, and I’m the father of all these things. But if you ask me, the first emoticon was the exclamation mark, because it was text that conveyed emotion without spelling it out in words. And I wouldn’t say emojis have wiped out emoticons; I mean, there’s the rebel underground. My friends and I who are computer scientists still use the text ones.

Of course communicating with pictures is hardly a new thing.

I mean we’re back to the hieroglyphics. But for conveying very simple things efficiently, that’s what these things are good at. I don’t think you can write a love sonnet or something using these. There’s a place for language, and there’s a place for this. People have said that it’s sort of like a graphical rimshot — a sign for stop here and laugh. So it’s a crude kind of communication, but sometimes that’s just what you need. Obviously, you can say more things with an emoji, but on the other hand, there’s such a great variety of them that it gets hard to tell what’s being said.

How much of the fascination with emojis do you think is generational?

Every generation wants to have their own secret code that shows they’re not the old fuddy-duddies and that their parents won’t understand.

What about brands and marketers using them?

For advertising, I guess, whatever works. Somebody apparently obtained a trademark on the frownie face — my frownie face — the text one — for office stationary use. Now if I ever wanted to sell a piece of office stationery with a frownie face on it, I will have to pay them. But it’s kind of fun when you see phone companies or somebody with text smiley faces in their ads. I guess they’re trying to be retro and cool.

If the emoticon spawned the emoji, what comes next?

I never would have predicted the emojis, so maybe I’m not the right person to predict what’s next. But these days, if I want to send someone a smiley face, it’s so much easier to send someone a selfie — that’s me smiling. I don’t know if the graphical emoji will disappear or not. But the text ones I think will be used as long as people are sending text because they’re just handy. But once there are 10,000 of these emojis, it becomes hard to find the right one. So they may choke on their own success.

More in Marketing

YouTube’s upmarket TV push still runs on mid-funnel DNA

YouTube is balancing wanting to be premium TV, the short-form powerhouse and a creator economy engine all at once.

Digiday ranks the best and worst Super Bowl 2026 ads

Now that the dust has settled, it’s time to reflect on the best and worst commercials from Super Bowl 2026.

In the age of AI content, The Super Bowl felt old-fashioned

The Super Bowl is one of the last places where brands are reminded that cultural likeness is easy but shared experience is earned.