US Airways responded to its now-infamous sexual turbulence tweet with standard protocol: an apology.

We apologize for an inappropriate image recently shared as a link in one of our responses. We’ve removed the tweet and are investigating.

— US Airways (@USAirways) April 14, 2014

The incident raises the question of when a brand should apologize on social media in the first place. If the social Web is meant to facilitate “human” connections between brands and customers, then one would think brands should be empathetic when dealing with customers’ problems to the point of saying “sorry.” But it’s not always that cut and dried. There’s a good case to be made that brands, in the desperate need to be accepted, are apologizing way too much — and to their own detriment.

“Would you feel confident that a brand that is constantly publicly apologizing is going to provide you with a quality experience?” said Rick Liebling, head of global marketing at social media analytics company Unmetric. “It takes the focus away from what you want to accomplish.”

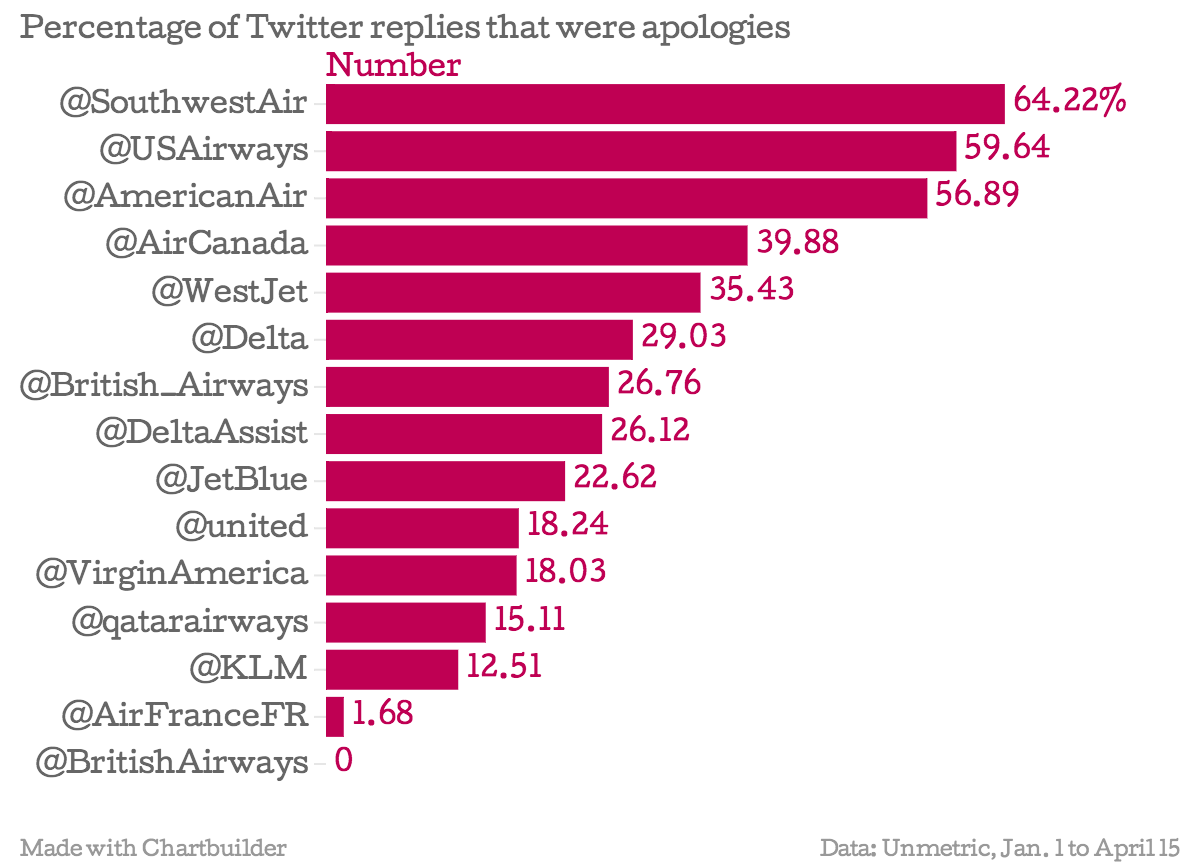

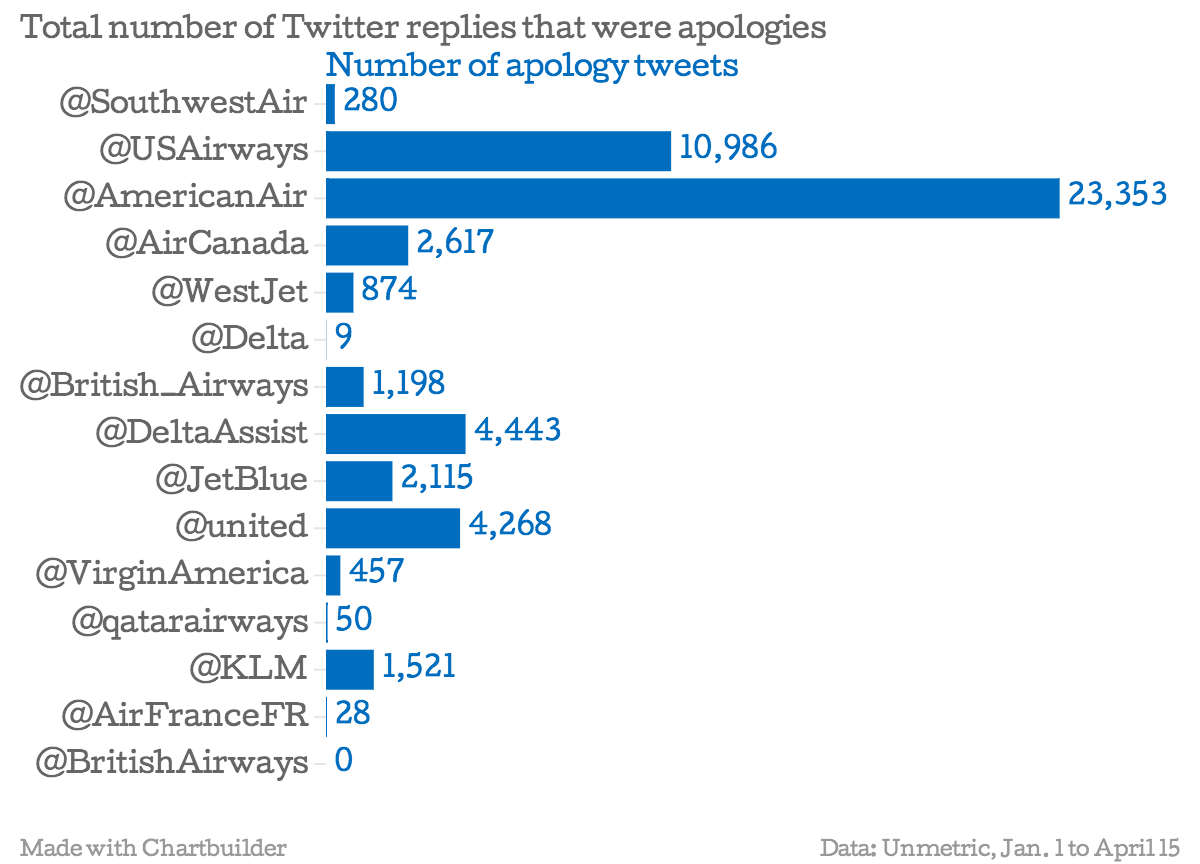

Unmetric provided Digiday with data on how apologetic different airlines were on Twitter between January and April, and the results show that US Airways’ recent Twitter apology was no anomaly. American Airlines and US Airways, with which it is merged, are the two most apologetic airline brands on Twitter, according to Unmetric.

Southwest may have sent a higher percentage of sorry tweets during the time period, but its volume of “sorry” tweets was just a fraction of the number American and US Airways sent.

American Airlines spokesman Matt Miller said the two brands do not have an established protocol for deciding when to say sorry. The brands do treat customers’ tweets as though they were inbound calls for flight reservations, he said, which would explain its high number of customer responses on Twitter. Everyone on the social networking team has experience booking reservations and can therefore make flight adjustments based on customers’ tweets, he said.

But apologizing can exacerbate a problem. Twitter is an echo chamber, leading some brands to incorrectly believe that Twitter outrage reflects the feelings of the general populace. After all, Twitter can sometimes resemble an unruly mob that preys on the weak. Just ask Justine Sacco. An apology didn’t seem to help her.

“Sometimes the knee-jerk reaction to make the apology can make the issue larger than it needed to be,” Liebling added. “The original tweet, though obviously offensive and inappropriate, wasn’t a safety issue or directly related to their business in other ways. Once they saw the mistake they took it down and that was most likely the end of it. With the apology, literally thousands of people who would not otherwise have known about it saw the retweets and, at that point, possibly became curious and looked for more information about the issue.”

Matt Britton, CEO of digital agency MRY, recounted a similar experience in which a previous client was being harassed by a cohort of mommy bloggers. MRY research showed that virtually none of the brand’s customers even knew about the supposed PR fiasco. The story only caught those customers’ attention after the brand apologized.

There are surely times to apologize for brands, but there is also a ritualistic, almost robotic aspect to the brand apology. We have now come to expect it on cue directly after the social media screw-up.

“Canned Twitter apologies aren’t the best way of dealing with customer complaints,” DigitasLBi’s director of social and content strategy, Jill Sherman, said. “Not only does the fake apology eat up most of your 140 characters, it doesn’t feel authentic.”

Image via Shutterstock

More in Marketing

YouTube’s upmarket TV push still runs on mid-funnel DNA

YouTube is balancing wanting to be premium TV, the short-form powerhouse and a creator economy engine all at once.

Digiday ranks the best and worst Super Bowl 2026 ads

Now that the dust has settled, it’s time to reflect on the best and worst commercials from Super Bowl 2026.

In the age of AI content, The Super Bowl felt old-fashioned

The Super Bowl is one of the last places where brands are reminded that cultural likeness is easy but shared experience is earned.