Secure your place at the Digiday Publishing Summit in Vail, March 23-25

Everyone is outraged, and no one cares.

The new normal that made putting out fires part of brands’ 9-to-5 has also upended textbook social media practices: Although brands have been taught they need to respond to as much as possible and as often as possible, the sheer amount of vitriol and slights, real and perceived, over seemingly trivial #brandfails makes it impossible. And when a brand has a real crisis on its hands — Chipotle and Volkswagen, we’re looking at you — we’ve cried wolf so often it’s hard to know how much to care.

“We’re struggling,” said Sean Reardon, CEO of Moxie, an agency that works for brands including Chick-fil-A, UPS, Verizon and Coca-Cola. “If I pay attention to every single negative thing that could wrong, I could spend my day on this.”

Social media outrage has become the primary thread running through the cultural quilt. Everything is an “epic” or “cringeworthy” fail, and there is a gleeful gotcha at play when the Average Joe catches a brand stumble, however innocuous. Brands, ever protective of their image, and the agencies they employ not only can’t keep up — they disagree over whether they even should.

“Consumers are quick to jump on any bandwagon, and I want to tell clients, listen, the attention span is so small that they’ll forget about this particular mess-up quickly,” said one social agency CEO who preferred not be named because he didn’t want clients to think he wasn’t taking consumer outrage seriously.

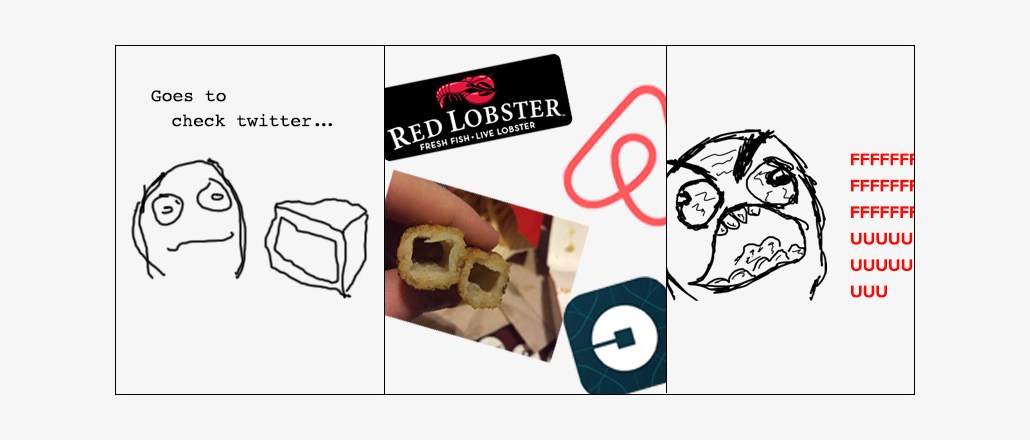

Take Bud Light: The Anheuser-Busch beer encouraged people to remove “no” from their vocabulary (a bad idea, to be sure, but probably more ham-fisted than deliberate) and the Internet went nuts. Uber and Airbnb changed their logos, and they were raked over the cyber-coals. Schadenfreude is fun! Especially given how hard brands try to ingratiate themselves with consumers. “Brand fails have become entertainment,” said Howard Belk, CEO of branding firm Siegel+Gale.

For Will McInnes, CMO of Brandwatch, which tracks online chatter, there is an upswing in the number of online fails — not because more are happening, but because social media shines a spotlight on them. (For some sense of scale, check out Slate’s dizzying “the year in outrage,” which tracked everything people got mad about in 2014.) “The public takes special notice of insensitive or awful social commentary because it’s easier to identify fails,” he said. “Fails are the negative that break away from the social narrative. Once the narrative takes a turn from anything but the expected, people notice and react, typically with outrage.”

Brandwatch analyst Kellan Terry said #brandfail has only been used as a hashtag 230 times since Jan. 1, but most of the time, people don’t use the hashtag when discussing displeasure with a brand — they just @ the brand itself. “The interaction and ensuing outrage are often so personal that people will just mention the brand to get its attention. They are not attempting to enter a larger conversation; just get their frustrations addressed,” said Terry.

Speeding up and dumbing down

George Nitzburg is an adjunct assistant professor at Teacher’s College in Columbia University who specializes in education and psychology. The digital ecosystem, he said, accelerates the speed with which opinions get made and also rewards a shorter attention span. Human beings have gotten used to this culture, which also allows for less impulse control. And people are also feeling more empowered: So when they tweet about Subway hiking up a footlong’s price to $6, Nitzburg thinks they feel that by voicing their opinion, they’ve contributed, potentially, to a change. That kind of brand slacktivism “certainly doesn’t feel trivial” to the person tweeting about it, although it might be to the rest of the world. Just expressing an opinion is often catharsis enough.

Digital has also sped things up on the execution side — “Fuck it, ship it” has become Internet shorthand for getting a product out the door first and debugging later. As businesses face increasing pressure to deliver, there’s less diligence on the communications front, said Scott Karambis, who leads communications planning at MullenLowe Mediahub. “It’s almost impossible to control for errors with that much detail and so little time,” he said. “So you try to deal with some degree of breakage.”

There are hashtag fails, and there are true failures

There is, of course, a point at which the breakage becomes too big to ignore. The recent E. coli outbreak at Chipotle and corporate malfeasance at Volkswagen ought, in theory, to generate more online outrage than, say, a dearth of mozzarella in McDonald’s cheese sticks. Distinguishing between substantive brand fails and simple egg-on-the-face fails becomes murkier. Karambis said he has simply gotten used to a low-level thrum of constant outrage at, say, basic logo snafus. “People hate changes,” he said. “I always say: You better know the upside, and it better be good because I guarantee there will be a downside.”

And so the marketing playbook has been rewritten: The first step after a spike in outrage isn’t to respond but to assess whether a failure has actually occurred — and how serious it is. “Is it one where the more we stir it, the more it stinks? Or is it someplace we’ve messed up?” asked Siegel+Gale’s Belk.

A social media manager who tweets for an airline said that while there has been no official change in policy, there is a feeling of, “It’s OK, they’ll forget about it tomorrow if we just keep very still.”

The very idea of a #brandfail also creates so much noise that it can, in some cases, insulate a brand, said Dipti Bramhandkar, who leads planning at Iris New York. “The problem with hashtag-brand-fail is it creates a diversionary issue,” she said. “Everything is a common denominator, with a 140-character role. It becomes entertainment. A bad spelling is a brand fail, and a bad language translation is a brand fail, and people getting poisoned is a brand fail.” The problem is there’s no standard way to quantify.

One way agencies and brands are looking at it is to focus on volume instead of sentiment, said Bramhandkar. And another is to build some sort of outrage-o-meter. “We don’t have yet the ability to differentiate between significant concerns and genuine concerns,” said Bramhandkar. “We need a scale, like we have warnings for storms.”

More in Marketing

In graphic detail: How Anthropic’s Pentagon refusal is paying off in downloads, brand trust and enterprise deals

OpenAI’s Pentagon deal seemed to spark uproar among its users, many of whom were against it. Anthropic’s refusal to agree to the terms was seen by users as the more trustworthy alternative.

How AI could disrupt retail media’s $38 billion search ad market

ChatGPT and other AI chatbots could divert shoppers from retailer sites, putting the $38B retail search market at risk.

‘Brand safety is moving from fear to curiosity’: Zefr’s Raddon on content-level accreditation – and what it exposes about the industry

The threat is no longer a discrete piece of bad content that a keyword list or a domain block can catch. Its volume.