What brands should learn from General Mills’ Facebook fiasco

Last week, consumers sounded the alarm when General Mills decided to update the legal terms on its website by adding an arbitration clause. First reported by The New York Times in a piece called “When ‘Liking’ a Brand Online Voids the Right to Sue,” the new terms appeared to cost consumers their right to sue in court if they merely “liked” General Mills’ social media pages, downloaded coupons from its website or entered any company-sponsored contests.

General Mills disputed that this was the case, but the people of the Internet were clearly not amused. One tweet summed up the sentiment nicely: “Apparently now if you even look in the direction of a General Mills product, you lose all legal rights.”

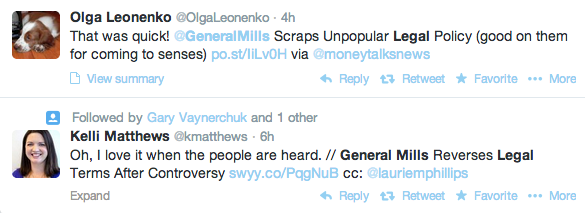

Because of the copious negative attention, General Mills announced in a blog post this past Saturday that consumers’ complaints have been heard and that as a result, the policy has been reversed and the original legal terms of use are back in place. The newest terms do not contain a “binding arbitration” clause.

In an effort to unpack and understand the legal changes and what these kinds of arbitration clauses really mean for consumers and brands, Digiday has put together an explainer.

Read on to get a walkthrough of what all of this legal stuff actually means and whether or not liking General Mills would have actually meant you couldn’t sue it:

What was the legal policy change that General Mills had initially introduced?

General Mills posted a note on its site that read: “We’ve updated our Privacy Policy. Please note we also have new Legal Terms which require all disputes related to the purchase or use of any General Mills product or service to be resolved through binding arbitration.”

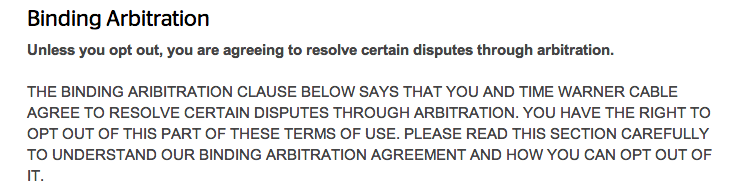

What does this “binding arbitration” clause mean?

As David Seligman, an attorney at the National Consumer Law Center, explained, “In broad terms, the clause at issue would prevent consumers from bringing claims against General Mills in court, and it also prevents consumers from bringing class action and collective suits — it requires consumers to arbitrate cases against General Mills individually.”

The part that everyone took and ran with was the notion that this meant that liking General Mills on Facebook meant losing the right to sue the company. Is that really part of what the clause covered?

Because General Mills has already reversed the policy and no claims have been settled under this policy, it isn’t entirely clear how the clause was meant to operate in practice and when the clause would actually apply. General Mills did post an explanation of the update saying that the clause had been mischaracterized and did not mean that liking the brand on Facebook meant that you could no longer sue the company. However, as Seligman noted, “The language of the clause was very broadly worded, so it seems like General Mills intended to be able to invoke the arbitration clause against people who interacted with it in a variety ways online.’

What is “binding arbitration”?

Arbitration is a private way of resolving disputes. It is established through contract, and judgement is made by a third-party arbitrator. There are a lot of arbitration administration firms set up to decide these cases. These kinds of cases are privately funded, and they are not government sanctioned or sponsored or anything like that.

Is that even legal to make it so that people can’t take legal action against a corporation?

These kinds of arbitration agreements very common. If you poke around different company’s websites and check out the “Terms of Use,” you will often be able to spot an arbitration section. As Seligman explained, the pervasiveness of arbitration clauses is a result of a 2011 Supreme Court case of AT&T Mobility v. Concepcion favoring arbitration and enabling companies to avoid class-action suits.

Why is this bad for consumers?

Class-action suits are one of the few ways consumers can band together and fight back against corporations. Class-action suits allow people the share the costs of taking legal action against companies and offer the option of confidentiality. By banning class-action through these kinds of arbitration clauses, this makes it very difficult for consumers to fight for their rights against corporations. Arbitration rulings are also kept private, unlike court cases, which become public record, which enables companies to keep these kinds of legal issues quiet. Seligman also pointed out that arbitration is generally biased towards corporations and against consumers and employees. It is generally the company that pays the arbitrator for each case, so arbitrators have financial incentives to do well by corporations.

Can you appeal an arbitration ruling in the way you could appeal a court ruling?

According to Seligman, it is not impossible, but it is incredibly difficult for consumers to effectively appeal an arbitration ruling to court.

Was it smart for General Mills to reverse the policy?

In the social media age, more and more brands are realizing the importance of actively listening and responding to consumers. This is a strong example of the power consumers hold to keep brand accountable, even when brands try to insert legal clauses that enable them to sidestep that accountability. General Mills has been transparent about the reversal and apologized in a blog post entitled “We’ve listened — and we’re changing our legal terms back.” People are expressing their support of the reversal on Twitter, so yes, it seems like a smart move for General Mills and shows its honesty and responsiveness as a brand.

Does this mean other brands need to rethink their arbitration clauses — is this a cautionary tale for brands?

If anything, it is just another lesson about the power of social media in getting corporations to address serious problems. But as mentioned, arbitration clauses are legal and prevalent, so it’s unlikely that brands will be taking them down just because of this — unless of course people start raising hell on Twitter against specific companies. “General Mills was public about it, so it caught people’s attention,” said Seligman. “The vast majority of companies already have arbitration clauses — I don’t think this will put pressure on companies to remove them, and there are all kinds of sneaky ways to put these things up.”

More in Marketing

Ahead of Euro 2024 soccer tournament, brands look beyond TV to stretch their budgets

Media experts share which channels marketers are prioritizing at this summer’s Euro 2024 soccer tournament and the Olympic Games.

Google’s third-party cookie saga: theories, hot takes and controversies unveiled

Digiday has gathered up some of the juiciest theories and added a bit of extra context for good measure.

X’s latest brand safety snafu keeps advertisers at bay

For all X has done to try and make advertisers believe it’s a platform that’s safe for brands, advertisers remain unconvinced, and the latest headlines don’t help.