Secure your place at the Digiday Media Buying Summit in Nashville, March 2-4

The Wall Street Journal’s native approach: ‘If it looks like a puff piece, nobody’s going to read it.’

A lot of publishers are looking to native ads as the cure of all that ails them, from declining display ad rates to programmatic advertising to viewability. The Wall Street Journal takes a more pragmatic view.

“I believe in native advertising, but I don’t believe it’s the answer to advertisers’ problems, and it’s not the answer to the publishing industry’s problems,” he said. That’s Trevor Fellows, who as global head of ad sales for The Wall Street Journal parent Dow Jones oversees its 1-year-old WSJ Custom Studios.

And yet, under him, the 32-person studio turned out upwards of 50 campaigns involving custom content (including native) in 2014, for clients including Mercedes, AIG and the MetLife Foundation. Twelve percent of ad revenue at the Journal last year involved custom advertising, including native. (Corporate parent News Corp doesn’t break out the Journal’s ad revenue, however.) Native contributed to a 2 percent increase in Journal ad revenue in the most recent quarter.

While other publishers have grabbed headlines with whiz-bang native ads — see The Atlantic’s treatment for Netflix’s “House of Cards” — the Journal has taken an understated approach. While The New York Times talks up Adam Aston, the editorial director of its T Brand Studio, the Journal doesn’t pitch its people by name; it has a few writers and editors who are supplemented by freelancers, but Fellows didn’t readily know their names. Its native ads go byline-free, Economist-style, lest they detract from the client.

WSJ’s ‘Faustian pact’

While other publishers from Condé Nast to Time Inc. are enlisting their journalists in the ad creation process, the Journal, whose managing editor Gerard Baker once famously called native ads a “Faustian pact,” maintains a hard wall between church and state. The newsroom only gets involved when its ethics committee reviews each native ad before publication. While the Times slightly shrank the size of its native ad label, Fellows said the Journal’s labeling has been unchanged since the beginning.

“It’s a very harmonious relationship,” Fellows said. “There’s definitely a church-and-state separation.”

And while the Times touts the Timesian quality of its native ads and Bloomberg, its data-informed campaigns, Fellows’ pitch centers on the value of its audience and campaigns that don’t just entertain, but inform.

“We’re one of the few titles that they read,” he said. “We’re probably the only way you can get a critical mass of the key decision-makers in the U.S.”

But it’s the Times that’s clearly winning on the PR front, getting extensive press coverage for a handful of highly produced, multimedia native ads for Netflix’s “Orange is the New Black,” Cole Haan and Shell and raising the bar for a format that was initially written off by skeptics as old-school advertorials with a new name.

“They have a different corporate culture in terms of getting attention,” Fellows sniffed. “But if you look at the New York Times, no one can name more than two of their clients. No more than you can name any more than two brands doing native advertising. Netflix hit a chord, and that was a year ago.”

Sour grapes? Maybe. But it’s hard to dispute his point that native advertising is difficult, for brands and publishers alike. Many brands aren’t prepared for the time it takes for branded content to make its way through all the approvals needed, and many Journal advertisers are risk-averse and in heavily regulated industries or want their ads to run in overseas markets, which further bogs down the process. While some brands are well staffed to create content, “others have a tiny communications team, don’t know where to start,” Fellows said.

Big revenue, smaller margins

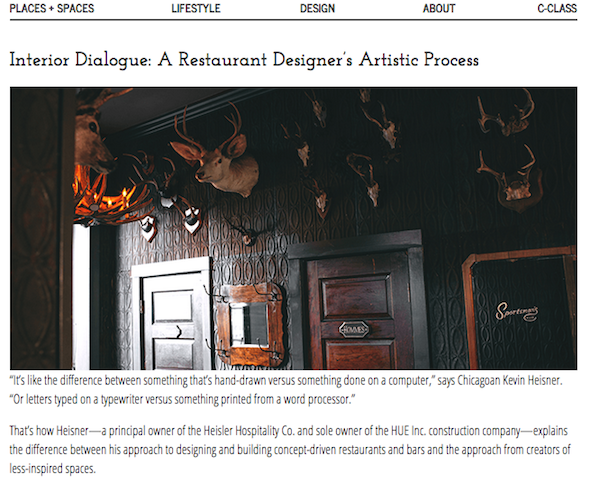

Native is hard to make profitable. Some publishers charge for either the content production or the media; the Journal charges for both, and a typical campaign, consisting of multiple articles with interactive infographics, runs $500,000. (Extrapolating that figure, the Journal would have made $25 million last year on custom content.) Still, the time involved makes it less profitable than display ads. A campaign, shown below, for Mercedes involved sending a photographer on a road trip in a C-Class to document the work of craftsmen and innovators.

For MetLife Foundation, it created a multimedia package (below) about the issue of financial inclusion around the globe. Fellows said the Journal has produced “some of the best ideas in the business,” but “it’s a lot of work. Even if it’s neutral to build, it’s time-consuming.”

And there are the inherent conflicts in native advertising, which is, after all, designed to mimic the host publication’s editorial content. For the reader to click on a native ad, it has to be at least as good as the editorial content surrounding it. But for a reputable news publisher like the Journal, the risks are high if its native ads ever leave readers confused.

The Journal’s understated approach has had the effect of leaving some in the ad community underwhelmed. Some say the paper (as well as other publishers) has done little to differentiate its offering beyond talking about its audience.

“Pretty much everyone has built a variation of that model,” said Jeremy Tate, vp, group director, media at Digitas. “I think they’re all trying to get it off the ground and understand how advertisers and users are responding to it. The offering is pretty similar.”

Some also have suggested that the Journal’s large and reliable circulation revenue stream, which reportedly accounts for some 45 percent of its revenue, has lessened the pressure on the paper to aggressively grow its native advertising.

Steve Rubel, chief content strategist at Edelman, speculated that the Journal’s native ads haven’t made a lot of noise yet because it has an affluent, paying audience.

“They appear to be taking a more measured approach. However, given the data they have on their readership, they maybe able to offer marketers a way to reach/engage qualified audiences through native content that might be hard to replicate elsewhere,” he said.

Fellows disputed the notion that the Journal’s subscription model has tempered the demand for results: “I would guarantee Meredith [Levien, the Times’ evp of advertising] and I have the same amount of pressure from our bosses.”

One of the pressures all publishers face is demonstrating that native ads actually translate to measurable results for advertisers. The knock against native is that it’s unproven, although that may have to change; some publishers say they’re getting more requests from advertisers to tie native to business-oriented results.

That hasn’t been the case at the Journal, where clients tend to use native for brand awareness and thought leadership. The recent MetLife Foundation campaign, for example, barely showed the brand. Like most publishers, the Journal still measures campaigns by traditional publishing metrics like time spent and shares, using analytics firms Moat and Chartbeat. The Times’ Levien made headlines when she said some of the Times’ “Paid Posts” have performed better than some of its traditional news articles. Fellows says such comparisons make no sense, given readership levels can vary so widely from one article to another. “I don’t think native is served by putting out hyperbolic claims about its effectiveness,” he said.

The Holy Grail: Utility

That’s not to say the Journal isn’t focused on making its native ads more engaging, with better ideas, video and infographics. As a B2B publisher, the Journal says its native ads ultimately need to not just entertain but inform. For Fellows, the holy grail would be for the content to be so useful that a Journal reader would tear or print it out and use it in a presentation. In fact, the studio worked up a proposal for an advertiser that includes graphics that are designed for just that purpose. In a seventh-floor conference room at the Journal, Fellows scrolls through the mock-up on a screen, clicking through its interactive infographics.

“We don’t think most people want to come to a site like ours and read content from an advertiser that replicates a normal article,” he said. “If it looks like a puff piece, nobody’s going to read it. It’s got to be at least as engaging as the content around it. They should feel more informed having read that content.”

Images courtesy of The Wall Street Journal, Sarah Gilbert

More in Media

Media Briefing: Turning scraped content into paid assets — Amazon and Microsoft build AI marketplaces

Amazon plans an AI content marketplace to join Microsoft’s efforts and pay publishers — but it relies on AI com stop scraping for free.

Overheard at the Digiday AI Marketing Strategies event

Marketers, brands, and tech companies chat in-person at Digiday’s AI Marketing Strategies event about internal friction, how best to use AI tools, and more.

Digiday+ Research: Dow Jones, Business Insider and other publishers on AI-driven search

This report explores how publishers are navigating search as AI reshapes how people access information and how publishers monetize content.