Secure your place at the Digiday Publishing Summit in Vail, March 23-25

Meredith Levien’s plan to save (or at least make money for) The New York Times

On Feb. 13, The New York Times news staff gathered to remember one of its most beloved writers, the media columnist David Carr, who had died suddenly at his desk the day before. Carr was the conscience of the Times, one of its staunchest defenders in the face of its economic uncertainty and cultural upheaval. So when one of the editors, Bruce Headlam, mentioned in his remarks how much Carr was a fan of Meredith Kopit Levien, the paper’s new ad chief, ears pricked up.

“I remember being struck by it,” recalled Dean Baquet, the paper’s executive editor. “Look how much things have changed that the newsroom has gotten together to honor one of its most valuable writers, and his editor talks about how much he liked the ad director. That was a moment for us.”

The need for speed and scale in publishing today has required media companies to embrace collaboration more than ever. As one of the most important and high-profile journalistic institutions, the Times has embraced change with uneasiness. Pushing it forward falls to Levien, 44, who after a year and a half with the company was named chief revenue officer last month — adding responsibility for consumer revenue — and whose relationship with the news side will be a big key to her success.

“The Times has arguably done more than any media company has to develop a paid model,” she said. “A lot of my own work will be to optimize what’s going on. Obviously, there’s work to be done in print-digital customer acquisition, but we also represent one of the world’s best brands.”

The Times is more stable than it has been in recent years, but it still faces big business challenges, which boil down to how the Times can continue to get more money out of new and existing readers and how it can continue the momentum on the digital advertising side.

Despite its growth in digital revenue, print still drives 70 percent of revenue, and is on the decline. The paper has increased consumer revenue with its introduction of digital subscriptions four years ago. Today, more than half the Times’ revenue comes from subscriptions, including its digital subs, which are projected to hit 1 million this year. But digital subscription growth has tapered off, and the paper has had a hard time shaking more money out of consumers with the four new niche products it has launched in the past year: NYT Now, NYT Opinion, Times Premier and Cooking.

Mobile now kicks in more than 10 percent of overall Times revenue, but that’s not enough, considering the Times’ digital audience is now more mobile than desktop. The Times has gotten accolades for its native advertising format, but it’s got to keep up when its peers have comparable offerings.

With these challenges in mind, Times president and CEO Mark Thompson looked around at his current leadership bench. Kinsey Wilson had recently arrived as a galvanizing head of digital. He, like Levien, was identified as an executive with broad abilities. With their divergent talents, Thompson felt it made sense to have one person overseeing both of major revenue streams. Wilson was promoted to evp of product and technology, and then consumer marketing and sales were combined and placed under Levien.

“The opportunity to give those two people joint leadership of this whole project for us made more and more sense,” he said.

Editorial enthusiasm

Levien seems well suited to the business and culture demands facing the Times today. Her introduction to the Times was as a high schooler in Richmond, Virginia, when her parents bought the Sunday edition. She was naturally interested in global news, and reading the Times helped shape her view of the world and developed a conviction about the Times’ role in a democracy. “One of the roles the New York Times plays in the world — and we have to keep doing, even as news becomes more personalized — is we have to keep telling people what they need to know.”

She attended the University of Virginia, where she worked at The Cavalier Daily. She did mostly writing and editing there, but switched to selling ads in her last year; she needed the money, and it was one of the few paying positions there. She launched her media career after graduation, when she moved to New York City, where she lives now with her husband Jason Levien, co-owner of major league soccer club D.C. United; and their 4-year-old son. While in her 20s, she got a job working for the Advisory Board, the consulting firm owned by David Bradley. After Bradley bought The Atlantic in 1999, he hired her as as ad director. She climbed the sales ranks at The Atlantic and later Forbes, where she became known as a hard worker who was bent on pleasing advertisers but also forged a strong relationship with the editorial side.

While at The Atlantic as ad director and associate publisher, former colleagues said, she was a devoted reader of the magazine (something that’s not necessarily a given on the ad side) and hung out with its high-profile writers like James Fallows and Scott Stossel.

“She had this enthusiasm for what we were trying to do editorially,” said James Bennet, who arrived as editor in 2006 a few months before Levien left for another Atlantic Media title, 02138 Magazine. “You had the sense she wanted to sell something she believed in.”

Elizabeth Baker Keffer, Levien’s former boss at Atlantic Media, remembered Levien’s strong work ethic. Once, under Levien’s watch, an ad was accidentally placed next to content that the advertiser stipulated it didn’t want to be opposite (Baker Keffer wouldn’t identify the client except to say it was in the auto industry). Levien offered to resign. “She took it on the chin in a big way; she wanted to protect the Atlantic,” Baker Keffer said. She was allowed to keep her job.

Warming to native

In her next position, as group publisher at Forbes, she was at the vanguard of the native ad obsession with BrandVoice, the magazine’s controversial ad product. Now, just about every publisher has a so-called native ad offering, but when Levien took Forbes’ to market in 2012, the idea of letting advertisers blog alongside journalists was considered heresy, even though the native format was a close cousin of the advertorials that have run in print for decades.

As such, she was not exactly welcomed with open arms when she was beamed up to the Times in 2013. Then-executive editor Jill Abramson had expressed doubts about native, as had Carr. So when the Times in 2014 introduced its own native ad offering, Paid Posts, the paper took a conservative approach, prominently labeling them as ads.

But soon after, the Times produced its Innovation Report, a blistering internal survey that criticized the newsroom for being slow to adapt to digital. On May 14, Abramson was abruptly fired, replaced by Baquet. The same day, Levien, touting the early success of Paid Posts, said at a 4As event that some of the Times’ native ads had performed better than traditional Times’ articles. The Times quickly realized the poor optics of that statement, and Levien has since dialed it back.

“I made a sloppy, unfair comparison, because the reality is we promote Paid Posts very differently than how we promote editorial, so it’s not fair to make an apples-to-apples comparison,” she told Digiday. “What I should have said is, the work is to create this marketer-driven, original programming that is at a quality level befitting the Times. Every piece of content out there is competing with attention with all of the surrounding content, pictures of your children, and mine. The Times has done things…that just performed extremely well from a time and attention standpoint.”

A year later, the newsroom has grudgingly warmed to native ads. Levien hired journalist Adam Aston, a former Businessweek editor, to head up the native ad group, T Brand Studio. Its best known to date, for Netflix’s Orange is the New Black on women in prison, which ran in June 2014, got some unqualified praise from the Times’ own journalists.

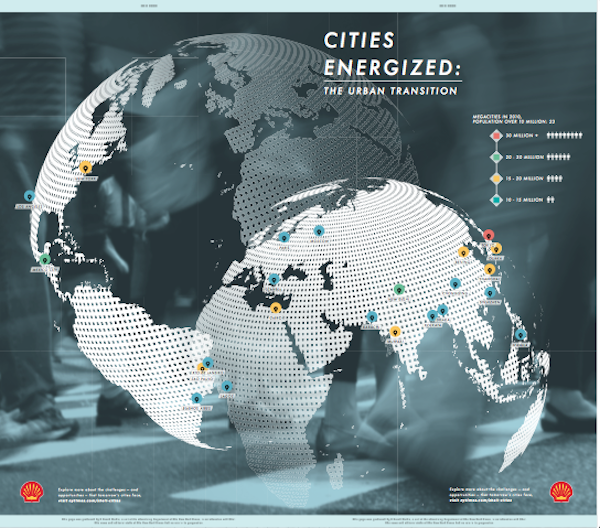

Overall, the ads, for clients including Cole Haan, Goldman Sachs and Shell, which ran the Times’ first native ad in print in November, have gotten more elaborate in presentation.

“I feel like I can talk with her about anything,” Baquet said. “I don’t think a week goes by that I don’t talk to Meredith.” Levien, he said, gets the importance of the Times’ mission, and her native advertising plan respects that. “It’s clearly labeled; to be frank, I think it’s high quality.”

She’s also endeared herself to the ad community, which gave numerous examples of the greater openness by the Times to interactions with editorial since Levien arrived. John Nitti, chief investment officer at Zenith, said he’s seen a greater presence by the Times at industry events like CES, where the paper hosted a 30-person dinner for his clients where Times journalists recapped the day’s events. “I think they’re being more strategic,” he said. “The idea is, you’re going to be at CES, we are, too.”

Ben Winkler, chief digital officer at OMD, cited a Times party it threw at South by Southwest where journalists like Maureen Dowd were brought out “to rub shoulders with the mucky mucks,” he said. Levien also offered to let him — an advertiser! — attend a Page One meeting with the editors (a Times spokeswoman said this is not a new practice, but many of its peers don’t follow suit, as Digiday found). “Talk about native advertising,” Winkler said. “To get behind the wall and see how the sausage has been made, that’s pretty special.”

Lessons learned

Levien’s to-do list is long. In terms of consumer revenue, she has to figure out how to keep the early success of the paywall going, transition print readers to digital and extend the Times brand to new audiences in the U.S. and abroad. The advantage of the consumer side is that it’s a more reliable source of revenue. But the Times has miscalculated people’s willingness to pay for its niche products; as a result, Opinion was shut down and Now was converted to a free product starting May 11 for lack of enough paying customers. Cooking remains free to the consumer for the foreseeable future.

The introduction of new products also created tension between the core and lower-priced product, and the increasingly-complicated subscription pricing has created consumer confusion. There are three main bundles in digital alone, not including the NYT Now (which is going free) and Opinion (folded) offerings.

The Times party line is that the paper has learned a lot from these products about the need to give people more time with a new product before charging them. “There’s a big body of learning around habituation and that being a precursor to a paid product,” Levien said. “I think a lot of good came out of the paid products that came out last year, and we’re applying that to how we go forward.” The Times says it’s continuing to experiment with apps.

Looking abroad

The Times also is starting to tap the overseas market, making it possible to buy the Times in local currencies and publish in local languages, like Mandarin.

“The way I think about it is, we have more than a third of our audience coming from outside the United States but a much lower percent of revenue coming from outside the U.S.,” Thompson said. Levien echoed that vision, saying: “There are a very large number of educated, curious, globally minded, English-speaking people in the world we have only just begun to reach. There is an absolute belief we can keep growing the paying audience of the New York Times.”

As for the ad side, Levien sees growth coming from four areas: native, mobile, video and overseas. On native, there’s effort going into making ad products that can live outside the Times and are suited to mobile devices, and branching out to advertisers abroad. The Times is making more inventory available to be bought programmatically. The paper has always pushed the quality of its video over its quantity but is starting to make concessions to the need for scale by seeking more distribution on social platforms and on the Times site itself.

As more publishers (and brands) get into native, the Times can’t rest on its success. Its signature products to date have been splashy one-offs, rather than the ongoing campaigns that are often required to change consumers’ minds. Other publishers, notably Condé Nast, are more flexible with advertisers, saying they’ll involve editorial staffers in creating ads. Asked if that puts pressure on the Times to follow suit, Levien gave an emphatic “No.”

“Here, we feel very strongly that we can do excellent marketer storytelling that is thoroughly labeled, label the hell out of it, have it come from a team that does it in a way that is befitting of sitting next to that gothic T,” she said. “Look, not every piece of content we’ve done has been great, but I think we’ve done enough great pieces that have gotten enough audience that we’re proving it.”

With ad buyers, the quality of its journalism and audience remains unquestioned, and they’re pleased to see more flexibility and the addition of new native and video products as well. But they want to be able to reach bigger audiences and buy video as a standalone product. They also want to see the Times embrace data-driven ad products and more programmatic selling.

“It’s a balance. Because of their heritage, they’re less likely to have scale and more likely to have quality audience,” Nitti said. “But in the age of scaling micro-segments, they need to figure out a way to create more inventory, either owned and operated or with distribution.”

Levien said this about the Times’ deliberate approach to video, but she could just as well be speaking of her overall way of doing things. “We want to get it right,” she said. “I think we’re maybe taking our time more than others are to get it right. And I think we’re pretty comfortable with where we are.”

Photo courtesy of Earl Wilson/The New York Times; modified by Matthew Fraher for Digiday.

More in Media

Media Briefing: As AI search grows, a cottage industry of GEO vendors is booming

A wave of new GEO vendors promises improving visibility in AI-generated search, though some question how effective the services really are.

‘Not a big part of the work’: Meta’s LLM bet has yet to touch its core ads business

Meta knows LLMs could transform its ads business. Getting there is another matter.

How creator talent agencies are evolving into multi-platform operators

The legacy agency model is being re-built from the ground up to better serve the maturing creator economy – here’s what that looks like.