Secure your place at the Digiday Media Buying Summit in Nashville, March 2-4

On the hunt for direct audience connections, publishers turn to desktop push notifications

Thanks to Facebook’s ever-shifting algorithm, publishers are scrambling to build direct audience connections through e-mail newsletters, revamped homepages and even desktop push notifications.

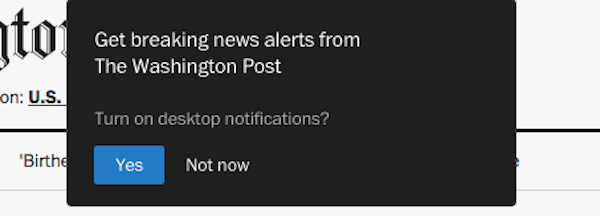

The Washington Post, Mic and Vice are all experimenting with asking visitors to their sites for permission to send them periodic notifications through their browsers. Chrome made it possible last year for websites to push notifications to people just like apps do, and Safari did before that.

When a reader arrives on a site, a dialogue box pops up that asks if they want to get alerts, which the publisher then pushes to them whether they’re on the site or not.

The Washington Post launched Chrome notifications in September, and since then, it’s gotten around 200,000 signups, which amounts to a 10 percent opt-in rate, said Joey Marburger, the Post’s director of product. The Post has sent around 20 notifications so far. The alerts, which range from breaking news to long reads, are getting a 33 percent click-through rate, he said.

Mic enabled desktop notifications seven months ago (and a month and a half ago on mobile), and 10 percent of Chrome and Safari desktop users have opted in to its alerts, said Anthony Sessa, vp of product and engineering at Mic. Subscribers spend 10 percent more time reading than do visitors who don’t come through alerts, he said. Mic also is looking into personalizing alerts as it gathers data on how people are using them, as well as selling advertising against them.

“A lot of new digital news companies are not homepage destinations,” Sessa said. “Side door is just out of our control. The more time we put into these direct channels, the more people are opting in. It’s our feed. We get to control that feed and it’s not a black box like the Facebook algorithm. We can drive the conversation the way we want at the time we want.”

LittleThings had similar results when it activated desktop notifications for its uplifting articles and videos. Its opt-in rate was only 1 percent (LittleThings thinks that’s because its site isn’t SSL, which adds extra steps to the notification signup process, eroding the user experience.) Still, 25 percent were clicking through. (LittleThings has put the experiment on hold while it evaluates whether to make its site secure.)

It’s early days for these types of notifications, but publishers are bullish on the tactic. Some see the potential for notifications to rival email newsletters, which many publishers have glommed on to because of their ability to forge direct connections with readers. The New York Times for one has had a team of 11 working on pushing out alerts to readers.

“It’s very powerful,” said Joe Speiser, co-founder and CEO of LittleThings. “It could become bigger than email. There’s no spam traps; it goes exactly to the people who signed up for it. You could move hundreds of thousands of people a day to a piece of content.”

Managing notifications is tricky. Publishers have to be cautious about pushing them out too often so they don’t overwhelm people. But whereas on mobile phones, alerts fill up more the small screen’s real estate and can feel personal because people take their phones with them everywhere, it’s easier for notifications to be lost on the desktop. “You can’t abuse it or you’re going to lose the audience you sign up,” Speiser said. Publishers also can take a risk with pushing out longer articles on desktop, since people are probably sitting at their desk when they get them.

Personalization is the natural next step. The Guardian took that approach with its alerts when its Mobile Innovation Lab began experimenting with mobile/desktop push notifications around big events including the Olympics, Brexit and the U.S. presidential debates this year. The Guardian saw website notifications as an opportunity to reach people who may come to the site daily but aren’t the die-hard app users.

After having run a dozen experiments, the Guardian learned that not all alerts formats work for the same news events. The Olympics afforded a good opportunity to let people personalize the alerts they got based on teams they were interested in. With Brexit, people wanted results but also responded well to a poll that asked them what most impacted their vote.

“Signing up doesn’t necessarily mean signing up for a lifetime or being pinged every time something happens that we think is important,” said Sasha Koren, who runs the lab with Sarah Schmalbach. “Something that affects people in a direct way are the things to key into.”

More in Media

Digiday+ Research: Dow Jones, Business Insider and other publishers on AI-driven search

This report explores how publishers are navigating search as AI reshapes how people access information and how publishers monetize content.

In Graphic Detail: AI licensing deals, protection measures aren’t slowing web scraping

AI bots are increasingly mining publisher content, with new data showing publishers are losing the traffic battle even as demand grows.

In Graphic Detail: The scale of the challenge facing publishers, politicians eager to damage Google’s adland dominance

Last year was a blowout ad revenue year for Google, despite challenges from several quarters.