Last chance to save on Digiday Publishing Summit passes is February 9

Netflix announced over the weekend that it has agreed to pay Comcast to ensure its movies and TV shows stream seamlessly in a deal that does much to highlight the increasing importance of digital content distribution. It also served to underscore how little people — from regular folks to the mainstream media — truly understand the Web’s infrastructure.

Much of the coverage so far has glossed over the complexity of how the Internet is delivered to consumers — and incorrectly characterized the agreement as a net-neutrality issue, according to Frost & Sullivan principal analyst Dan Rayburn. By all appearances, Rayburn says, the Comcast-Netflix partnership appears to be a typical, albeit confusing, deal between a publisher and an Internet service provider (ISP).

Understanding the deal and its implications on the Internet at large means understanding how the Internet works at a fundamental level. Digiday spoke with Rayburn as well as Mitch Stoltz, staff attorney at digital rights group the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), and a source close to the deal to sift through the news.

So, what is this deal about?

Comcast and Netlfix decided to work directly with one another. Netflix, like most media companies, merely publishes content. Because Netflix does not own any Internet infrastructure, it has to pay Internet service providers like Comcast to deliver its media to Netflix customers. Previously, Netflix was doing this indirectly; it was paying “transit providers” — third parties such as AT&T, Level 3, Sprint or Cogent — to access Comcast’s network. Now, Netflix and Comcast have decided they will be “cutting out the middlemen,” said Rayburn. Under the deal, Netflix servers housed at third-party data companies will now connect directly to Comcast’s network rather than through an intermediary. Neither party would disclose the terms of the deal.

I’ve been hearing a lot about “transit” and “peering.” What’s the difference?

A peering agreement is when two Internet infrastructure companies swap data between their respective networks. Sometimes this is done without money changing hands. Other times, both parties agree to build up their respective Internet capacities. But because Netflix doesn’t own any infrastructure, it can’t enter into a peering agreement with Comcast, according to the source close to the deal. Netflix can only offer cash. “Transit” relationships are when a company like Netflix pays a transit partner like Cogent for access to multiple ISPs. Because this deal is a direct relationship between Comcast and Netflix, it’s neither a peering nor transit agreement, per se. It’s what’s called an“interconnection agreement,” the source said.

Why’d they come to a deal?

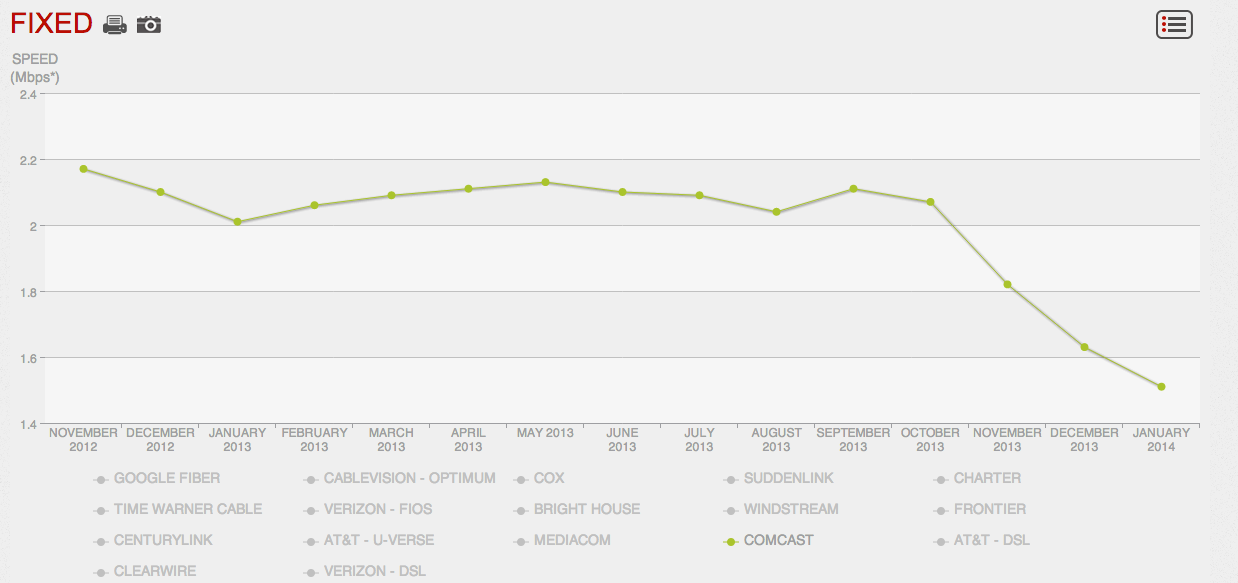

Because Netflix users were experiencing slower streaming times in recent months, and it wanted to ensure its customers could binge on “House of Cards” without having to suffer through buffering. Netflix reported on its blog that its traffic speeds had decreased in recent months on a number of major ISPs — including AT&T, Comcast, Time Warner and Verizon. This deal will make it so Comcast customers can watch “Girl, Interrupted” uninterrupted on Netflix.

That sounds great!

That’s not a question, but if you’re a Comcast customer, it indeed is. Verizon CEO Lowell McAdam said on CNBC on Monday he expects Verizon to sign a similar deal with Netflix.

What are the downsides?

Critics see the move as a possible violation of “net neutrality,” the concept that ISPs should treat all media served through their networks equally. Under net neutrality, large media companies would not be allowed to pay a premium to ISPs to ensure their media gets delivered more quickly than a competitor’s. Allowing large companies to do so would stifle innovation, net-neutrality proponents say. “I’m not so worried about Netflix,” the EFF’s Stoltz said. “I’m worried about the next data-intensive Internet business.”

Well, does it violate net neutrality or not?

Depends on how narrowly you define net neutrality. If Netflix is paying Comcast a premium for so-called Internet “fast lanes,” then there’s an argument to be made this doesn’t adhere to the concept of net neutrality. But since the terms of the deal haven’t been revealed, concerns that this is a violation of net neutrality are so far only speculative. Stoltz said that the deal appears to be a standard publisher-ISP partnership, although it raises a potentially dangerous precedent. “The sum total of deals like this one could have good or bad effects on the principle that anyone should be able to connect with anyone reasonably well on the Internet,” he said.

Rayburn, however, dismissed the idea that the partnership violates net neutrality. “It’s ludicrous. These deals are done everyday.” If anything, the deal will actually decrease Netflix’s Internet access costs. Why else would Netflix choose to work directly with Comcast when it has other Internet access options? he reasoned. “As a result of the deal, consumers will get better-quality video, and the cost will go down for Netflix,” Rayburn said. “It’s good for everyone.”

Neither Comcast nor Netflix would comment on the deal, but the source familiar with the negotiations hinted that it was a favorable one for Netflix.

Image via Shutterstock

More in Media

Brands invest in creators for reach as celebs fill the Big Game spots

The Super Bowl is no longer just about day-of posts or prime-time commercials, but the expanding creator ecosystem surrounding it.

WTF is the IAB’s AI Accountability for Publishers Act (and what happens next)?

The IAB introduced a draft bill to make AI companies pay for scraping publishers’ content. Here’s how it’ll differ from copyright law, and what comes next.

Media Briefing: A solid Q4 gives publishers breathing room as they build revenue beyond search

Q4 gave publishers a win — but as ad dollars return, AI-driven discovery shifts mean growth in 2026 will hinge on relevance, not reach.