Secure your place at the Digiday Publishing Summit in Vail, March 23-25

Dannie Fountain, an account representative at Google, receives LinkedIn messages on a weekly basis, typically a few times per week. That’s not a bad thing — except they’re always from fake profiles.

A couple weeks ago she got a message that read, “Hi Dannie- I am expecting your help to learn more about Google and available full time roles. Can we connect some time over phone for 15 minutes?”

The profile had no photo and no job information.

“The profiles typically have very limited information or are duplicates. If I search the name, I’ll see a second profile with more complete information. They are almost always asking questions about Google: How do I get hired, can you review my resume, can you submit a referral. Some of the more bold ones will ask or demand to set up time with me,” Fountain said.

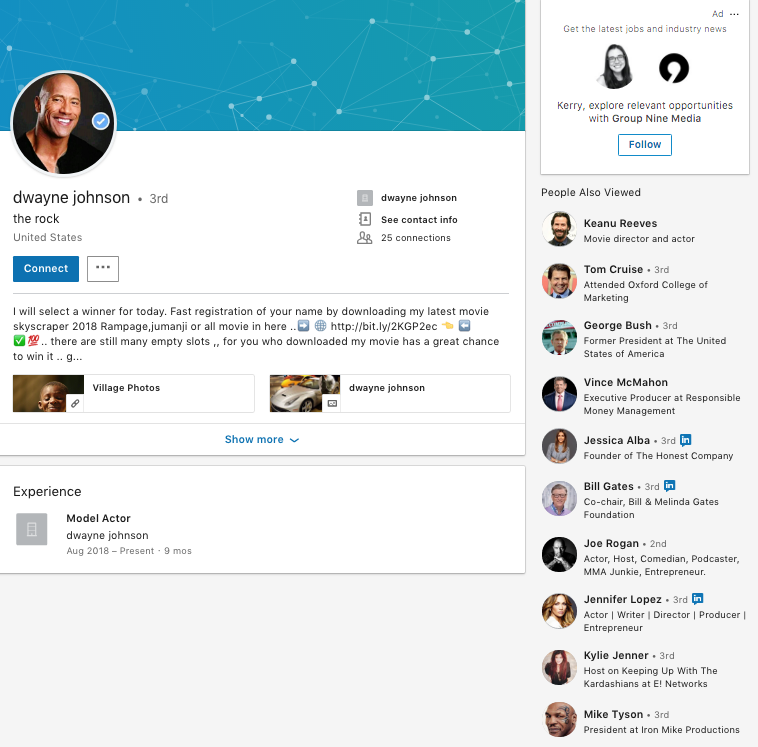

This is becoming more and more common for LinkedIn. The professional networking site, which touted 575 million registered members in August 2018, is filled with profiles with multitudes of issues, from profile photos pulled from Google images to an ambiguous job title at a fake company. Some of them, such as this profile, even comes with fake verified checkmarks.

These profiles then request to connect with the millions of legitimate users on LinkedIn or, if they pay for LinkedIn Premium, have the ability to just message users with peculiar asks.

Execs in the industry told Digiday while they find LinkedIn a valuable tool for their profession — to network and to keep up on industry news, for example — the amount of spam they receive leaves them frustrated. And it’s not a good look for LinkedIn, which proclaims a “simple mission” to “connect the world’s professionals to make them more productive and successful.” When users have to manage connection requests from fake profiles, LinkedIn becomes a time waster rather than a productive tool. While LinkedIn has worked to improve its product by introducing video and more sophisticated ad tools, the platform is still plagued by inauthenticity. It’s unclear how many fake profiles exist on the site.

“Fake accounts are a violation of our terms of service and we take action against them. When we identify bad actors, we take appropriate action, which often includes a permanent restriction from LinkedIn. We use a variety of automated techniques, coupled with human reviewers and member reporting, to keep our members safe from all types of bad actors and abuse. If members encounter something that makes them uncomfortable, suspect someone might not be representing themselves honestly or see inappropriate behavior like harassment or inaccurate content, we ask that they report it to us immediately and know that they can always block another member or remove a connection,” emailed Paul Rockwell, LinkedIn’s head of trust and safety.

Despite LinkedIn’s commitment to identifying and banning, inauthentic accounts persist.

“ALL. THE. TIME,” texted Vincent Orleck, social media manager at Arizona State University, when asked how often he sees inauthentic profiles on LinkedIn. “It’s pretty bad. Messages have bad syntax, spelling, and just weird requests overall. Then there are the somewhat-off accounts featuring female models and the like.”

Kirsten Suddath, vp of finance and operations at ad buying platform Flytedesk, said the number of fake accounts she has seen has increased in frequency over the last several months. She typically receives one to two connection requests per week from profiles she believes to be fake. The profiles often feature a profile picture of a woman seemingly in her late 20s to late 30s, and their note always says, “Nice to meet you.” Her response has been to not engage.

“I’ve previously just rejected the connection request, but from now on, I’m going to report them. LinkedIn is a great tool for us. It’s the primary tool that we use for top-of-funnel recruiting on key positions for Flytedesk, so I am hopeful that LinkedIn will respond and take action soon,” Suddath said.

While fake accounts on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter are abundant and known for spreading misinformation or boosting follower counts for fame, inauthentic profiles on LinkedIn seek the attention of business people.

The incentives are varied. Some inauthentic profiles send over phishing scams. Others can create a vast network of connections and then request to download their contacts and therefore could build email lists (The functionality has been limited by LinkedIn’s privacy tools released last year).

LinkedIn’s Rockwall said his company didn’t make that change with fraudulent activity in mind.

“We routinely look at ways to provide clarity and control. We made this change with our members in mind. Members have control over who can download their email address via a data export,” he emailed.

But just because the privacy setting to disable downloading your email address is there doesn’t mean every LinkedIn user is taking advantage of it.

“There’s a lot more to gain by being fake on LinkedIn than Instagram. I think it’s more high value. You can still export email addresses, and there’s really good money in email lists,” said David Shadpour, CEO of marketing company Social Native.

Shadpour said he consistently receives requests to connect from sketchy accounts. But one of the most nefarious uses of fake LinkedIn accounts he learned through his in-house recruiter. The recruiter showed Shadpour a profile of someone who looked like the ideal job candidate: Harvard undergrad, Stanford MBA, years of sales experiences at Microsoft and then Google.

“This is a genius fake profile because if I’m a headhunting firm, how do I get lead gen? A recruiter reaches out to this ‘candidate’ with, ‘Hey, we’re actively hiring for salespeople,’ and then two days later I get an email from a recruiting firm that says, ‘Hi, we hear you’re hiring for salespeople,’” Shadpour said.

Brett Petersel, who’s currently working at marketing agency Epic Signal, said he receives suspicious requests from accounts in Singapore, Indonesia and India. They all work for random companies, many of which don’t actually exist.

“I have blocked a number of profiles who claim to be recruiters for this one particular company. I’ve looked it up on Google, and people said, ‘It’s all a scam.’ Another case, the company was real. However, the ‘recruiters’ were not and had a different URL that led to the site,” Petersel said.

More in Marketing

‘The conversation has shifted’: The CFO moved upstream. Now agencies have to as well

One interesting side effect of marketing coming under greater scrutiny in the boardroom: CFOs are working more closely with agencies than ever before.

Why one brand reimbursed $10,000 to customers who paid its ‘Trump Tariff Surcharge’ last year

Sexual wellness company Dame is one of the first brands to proactively return money tied to President Donald Trump’s now-invalidated tariffs.

WTF is Meta’s Manus tool?

Meta added a new agentic AI tool to its Ads Manager in February. Buyers have been cautiously probing its potential use cases.