Global economic crisis sparks reappraisal of online ad spending by brand marketers

Weaker economic cycles suck out inefficient ad spending like a vacuum. This downturn is no different.

Fears of a recession, sparked by the war in Ukraine and acute tightening in fiscal policy to soften high inflation, have all but squashed top-line growth for many companies, forcing them to scramble for efficiencies to stretch profit margins.

Wasted advertising is likely to top that list — and for good reason. Not only is it a notable source of potential savings but, more importantly, it can help businesses unearth pockets of growth.

“Based upon our clients feedback, advertisers are concerned about the ROI they are currently experiencing from walled garden platforms (Snapchat, Twitter, Facebook, Google, etc),” said Mark Walker, CEO of ad tech group Direct Digital Holdings. “Clients are reassessing their spends and searching for more cost efficient digital advertising sources that are more transparent and open in their measurement in delivering an efficient ROI.”

The earnings updates from the largest online media owners last week alluded to it. Then attempts to explain those updates made it abundantly clear. Turns out, ad dollars weren’t just being slowed over the first half of the year. They were being rationalized and invested in the areas that really work.

“Advertisers have begun to question the big online platforms but still rely heavily on them for their advertising activity,” said Jide Sobo, director of digital solutions and partnerships at Ebiquity Group. “We see little evidence of brands backing away from these platforms based on our client spend. Nevertheless, brands continue to challenge the platforms over brand suitability and responsible practices.”

That would explain why search advertising has held up so far this year. To the point where there’s a clear divergence in growth between search and display ads.

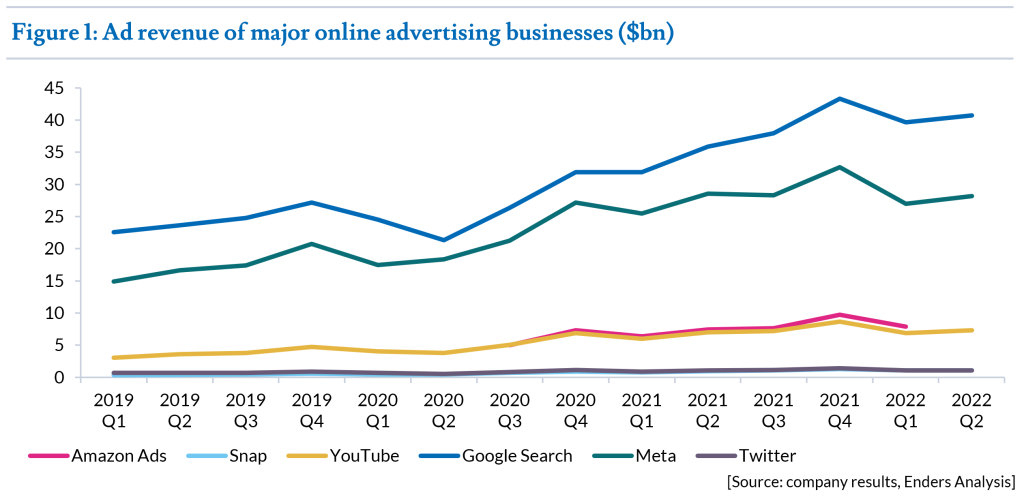

Search ads are highly effective, and the data signals search relies on are robust (it’s basically contextually targeted). It is seen more as a cost of sales than an optional expense. No wonder it’s the last thing to be cut by brands worried about the short-term bottom line. The numbers back this up. Growth in ad spending on YouTube, Twitter, Meta and Snap has slowed relative to advertising on Google search and Amazon, per data collated by Enders Analysis.

To be clear, these cuts are likely to be uneven. What the current rationalization of ad spending is making unequivocal is that not all direct response advertising is created equal. If anything, it’s driving a divide between higher and lower funnel direct response advertising, said Jamie MacEwan, media analyst at Enders Analysis.

There are, however, arguments for both sides. It’s no secret that higher funnel advertising is harder to link to purchases (increasingly so, given stricter restrictions around third-party addressability), has lower short-term returns and is susceptible to more wastage. That said, marketers need to generate new demand (irrespective of a recession) and that can’t be found at the lower end of the funnel.

“Our ability to improve effectiveness of reach and quality of reach is allowing us to drive cost per effective reach down both in digital and TV,” Procter & Gamble’s chief financial officer Andre Schulten told analysts on the company’s earnings update last week. “We have developed a strong capability to target better both on TV as well as in digital. Our ability to improve effectiveness of reach and quality of reach is allowing us to drive cost per effective reach down both in digital and TV.”

The dilemma every senior market at these advertisers is grappling with is how much online ad dollars to cut and where to spend what they have left as there’s no consensus on the state of the economy.

Its not a new problem, of course. Digital advertising is historically an area marketers turn to make cuts as it’s always been easier to pull back digital dollars than TV (particularly upfront) commitments. While marketers could exercise their option to pull money out of the linear TV market, fortunately for TV networks in the U.S., it’s an election year, and the surge of on-air political ad spending may help compensate for any negative impact. Online media owners, on the other hand, may not be as fortunate.

This spending reappraisal is a tall order for marketers. Not least because it means eating a big slice of humble pie. They have to admit they’ve spent tens of millions of dollars on advertising that at best is inefficient and limp, at worst fraudulent. These are tough issues to reconcile for marketers. Maybe that’s why they find it so hard to rein in online advertising — against their better judgment. That said, the results speak for themselves.

When Procter & Gamble turned off $200 million in online ad spending in 2017, the marketers there saw no change in business outcomes. The same year, Chase’s marketers cut the number of sites it advertised on from 400,000 to just 5,000 and saw no change in business activity. When Uber’s marketers turned off their paid app install budgets in 2017, the app installs continued. There’s a lot of ad spending inefficiencies out there.

“Advertisers need to retake control, and start tracking their ad spend, key media metrics and KPIs themselves,” said Philippe Dominois, CEO of media management firm Abintus Consulting. “Having their own media performance tracking allows them to identify ad spend inefficiencies right away and optimize their media performance & ROAS over time.”

No, these aren’t new issues. Marketers have long bristled at the fact that they have to trust that ads bought on platforms like Google and Facebook are as effective as they say they are. It’s just harder to accept this fact when the c-suite won’t.

“Quite frankly, I think what you’re seeing is those platforms becoming less attractive to advertisers as their limitations become clearer,” said Ian Whittaker, an equities research analyst at Liberty Sky Advisors. “It’s a structural not a cyclical thing.”

More in Marketing

WTF is the CMA — the Competition and Markets Authority

Why does the CMA’s opinion on Google’s Privacy Sandbox matter so much? Stick around to uncover why.

Marketing Briefing: How the ‘proliferation of boycotting’ has marketers working understand the real harm of brand blockades

While the reasons for the boycotts vary, there’s a recognition among marketers now that a brand boycott could happen regardless of their efforts – and for reasons outside of marketing and advertising – that will need to be dealt with.

Temu’s ad blitz exposes DTC turmoil: decoding the turbulent terrain

DTC marketers are pointing fingers at Temu, attributing the sharp surge in advertising costs across Meta’s ad platforms to its ad dollars.