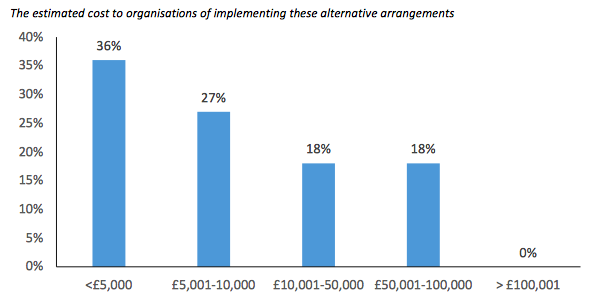

Since the fall, companies that transfer data between the U.S. and the EU have been having some headaches — headaches costing up to £100,000 ($149,000), according to the Direct Marketing Association (DMA).

Oct. 6 saw the landmark ruling between Max Schrems and the Data Protection Commissioner that invalidated the U.S. and EU Safe Harbor agreement, a blanket framework that allowed for the free transfer of data between the U.S. and the EU. Some 35,000 organizations were signed up to Safe Harbor, allowing them to transfer data, ranging from employee payroll information to customer purchasing history, across the Atlantic.

For this interim period before a new Safe Harbor 2.0 can be agreed, companies have had to use workarounds to avoid breaking the law and face fines.

The DMA anonymously polled its U.K. members, some of whom include Barclays, BT and Sky, marketing agencies and suppliers, and found that introducing alternatives to Safe Harbor is costing 18 percent of companies between £50,000 and £100,000, ($74,000 and $149,000). While nearly two-thirds (63 percent) report that it’s costing less than £10,000 ($15,000).

In the last two months, companies that want to continue transferring data across the Atlantic have had several options: continue transferring data between the two regions and risk compliance penalties (which 43 percent of DMA respondents are doing) or produce legal documents for each data transfer. These documents include contract clauses (30 percent) or binding corporate rules (10 percent) — these require legal teams and data importers and aren’t exactly quick or cheap.

Model contract are the fastest — they can be executed within a day as long as the firm’s lawyers and data teams are all available. Some companies, like Mailchimp, offer clients downloadable standard clause forms to make it as easy as possible to comply with regulation.

But these aren’t even remotely watertight. “Even when using model contract clauses, you still don’t know if the U.S. government is reading your emails,” said Eitan Jankelewitz, who works at media lawyers Sheridans. “We’re just another court case away from finding out that that doesn’t work either. Currently, they are lawful, but we don’t know how long for.”

“Model clauses are plainly inadequate,” said Richard Lack, director of EMEA sales at software firm Gigya. “They may bridge the gap legally as an interim process, but really everyone is driving toward hosting data within EU.”

Which means the small- and medium-sized companies — some 60 percent of businesses that were Safe Harbor certified — are feeling the pinch. “Companies that can’t afford regional data centers, which cost several million of pounds to run annually, will just fail to expand internationally,” said Lack. “It is just part of international trading now that you have to deal with various regional data privacy legislations.”

The DMA’s research will aid discussions on how the European Commission and the U.S. Department of Commerce can agree on a Safe Harbor 2.0, but some sources say the U.S. needs to pass more laws to ensure European citizen data is handled securely.

More in Media

Walmart rolls out a self-serve, supplier-driven insights connector

The retail giant paired its insights unit Luminate with Walmart Connect to help suppliers optimize for customer consumption, just in time for the holidays, explained the company’s CRO Seth Dallaire.

Research Briefing: BuzzFeed pivots business to AI media and tech as publishers increase use of AI

In this week’s Digiday+ Research Briefing, we examine BuzzFeed’s plans to pivot the business to an AI-driven tech and media company, how marketers’ use of X and ad spending has dropped dramatically, and how agency executives are fed up with Meta’s ad platform bugs and overcharges, as seen in recent data from Digiday+ Research.

Media Briefing: Q1 is done and publishers’ ad revenue is doing ‘fine’

Despite the hope that 2024 would be a turning point for publishers’ advertising businesses, the first quarter of the year proved to be a mixed bag, according to three publishers.